Liminal is not a word I can honestly say was active in my vocabulary before this autumn. But it is now. I’ve been learning a lot about liminal places lately, and it has to do with my reading, especially in the second half of 2021.

Before this, if you said liminal to me, I’d probably think subliminal. And probably specifically subliminal advertising.

Liminal and subliminal

Subliminal advertising is advertising sneakily concealed in fraction-of-a-second images inserted into otherwise innocent films. Or it’s a form of product placement where certain objects are used in a film or TV show, though without being referenced. For instance when an actor opens a laptop and the viewer sees the manufacturer’s logo – perhaps an Apple. Or it might be the smell of baked bread in the air of a supermarket. Or the incessant jingling of Christmas music designed to remind shoppers of the approaching Christmas gifts deadline.

That’s subliminal: below the level of conscious thought. OK, but what then is liminal?

Faced with a word I’m not sure of, my go-to reaction is etymology. Etymologically, liminal relates to the Latin limen (threshold), and to the Roman name for the frontiers of their empire, the limes. It’s also related to the rather more common English word limit. So a liminal place – or liminal space – must have to do with thresholds, borders, frontiers, limits; and what do you do faced with one of these? You may hover around on it for a while, but most likely, you’ll cross it.

The reason I’m so taken up with liminal places at present is entirely due to finding the phrase used to talk about a concept in fantastic and magical realist literature. Specifically in some titles I’ve recently read.

The Midnight Library and Piranesi’s House

For example, in The Midnight Library by Matt Haig, a book about overcoming suicidal despair. Nora Seed, the protagonist, has lived a relatively short life that has left her, at the beginning of the novel, in a state of despair. The death of her cat in a road accident is the final straw. She decides to commit suicide. But instead of dying, she finds herself in a liminal place. The Midnight Library exists between life and afterlife. Opening one of the books taken from the Library’s shelves allows Nora to step into and experience alternate, parallel existences.

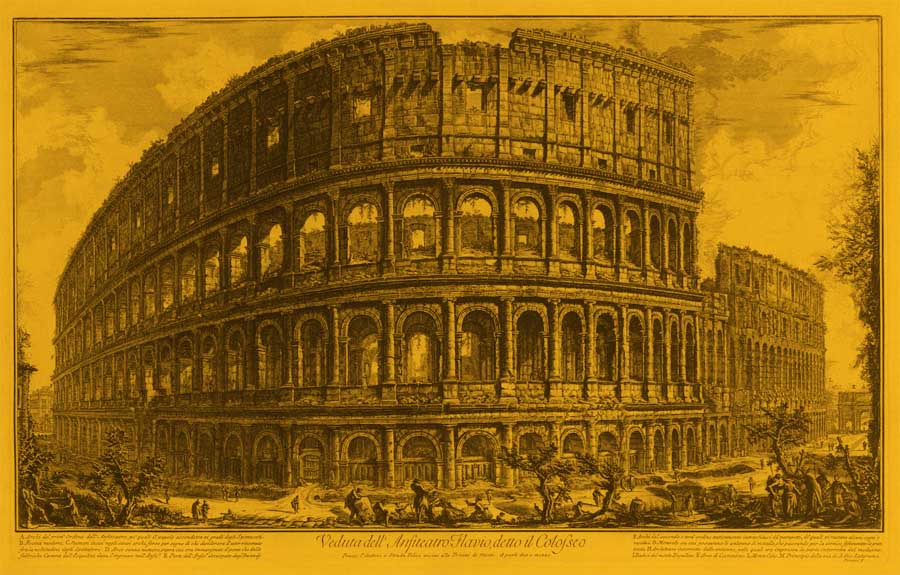

In another book, Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi, the liminal space is reached either through magic or, apparently, through a person’s simple conviction of its reality. In this book the protagonist, called Piranesi, seems to have become lost in a kind of infinite architectural maze. He calls it the House. It is a place subject to flooding and inhabited by fish and sea birds. He lives a kind of Crusoe existence, exploring, mapping and speculating about the House, though without (to begin with) understanding how he comes to be there.

Although Piranesi’s House only seems to connect to our world, the author implies that it is a liminal place with connections elsewhere. She does this in several ways. The various sculptures that decorate the architectural spaces seem to point to other worlds and other mythologies. The floods and the birds appear to sweep in from elsewhere. A character who appears briefly, The Prophet, describes the House as a “distributary world”. The novel’s epigraph is a quotation from The Magician’s Nephew by CS Lewis.

The Wood between the Worlds

In the seven books of Narnia, The Magician’s Nephew is the only one that makes use of a liminal place. (In fact, two liminal places.) The protagonists, Digory and Polly, are tricked by Digory’s uncle into travelling to the Wood between the Worlds. This is a liminal place from which the children can return to their own world, or travel to other worlds through the various ponds among the trees in the Wood. In this way they visit a decayed city (which resembles Piranesi’s architectural labyrinth) and inadvertently rescue a sorceress. They take her by way of the Wood to Narnia at the moment of its creation. The sorceress becomes the White Witch who appears in later Narnia stories.

(Incidentally, Digory’s uncle, the magician, is Andrew Ketterley of an “old Dorsetshire family”. Piranesi interacts with The Other, who comes regularly from our world into The House. The Other is revealed as Dr. Valentine Andrew Ketterley and his personality seems very similar to that of Digory’s uncle. In the words of the epigraph: “I am the great scholar, the magician , the adept who is doing the experiment. Of course I need subjects to do it on.”)

The Multiverse and the Darkened Wood

Both The Midnight Library and the Wood in The Magician’s Nephew play with the idea that we live, not in a universe but in a multiverse, a place where many worlds, or even universes, exist in parallel. Even Piranesi’s architectural labyrinth of a House exists in a parallel existence to the world we call real. Although all of these stories are fiction, the idea of the multiverse has a grounding in quantum physics, which borders on philosophy. (And there, the border between physics and philosophy, is another liminal place.)

Although the idea of multiple universes had been posited before, the modern quantum physics version is credited to Erwin Schrödinger. One of his lectures, in Dublin in 1952, is cited in the Wikipedia article on the subject. CS Lewis published The Magician’s Nephew three years after Schrödinger’s lecture. Just an observation.

Probably a more relevant association (for a classiscist like Lewis) would be to the opening of Dante’s Divine Comedy.

Midway through life’s journey

I woke to find myself in a darkened wood,

Where the right road was wholly lost and gone.

The Attic Corridor

Playing around with these ideas I found myself wondering if there are books that are not fantasies that make use of liminal places. Are there concrete, real world liminal spaces?

Of course there are.

For instance, the other liminal place in The Magician’s Nephew. (I said there were two, didn’t I?) It’s even pointed out in the book and used to explain the Wood between the Worlds metaphorically.

On a rainy day when they can’t go out to play, Digory and Polly explore a narrow attic space they have discovered. It’s a corridor of sorts and runs the length of the terrace of houses where they live, just under the eves. The attic corridor allows access to all the attics of the terrace. It is a counting error they make as they crawl along the corridor from one rafter to another that leads them into Digory’s uncle’s study. To become the subjects of his experiment. In this reading, the attic corridor is a liminal place, like the Wood between the Worlds.

Searching for real world liminal spaces I find a surprising number of references. (The number surprised me.) Corridors, stairwells and lift shafts – places that exist as routes to different floors, rooms and buildings – can all be liminal places. Empty, abandoned and non-functional buildings likewise. Streets, especially empty streets or streets at night, can be liminal, and so can places of transit like railway stations and airports.

Airports

My thoughts go to a book I read earlier in the year, Flights by Olga Tokarczuk. In this book it is often an airport that is the liminal place, if it’s not a train station. Flights is an episodic novel and contains a number of different stories. These take place in different times and places and involve different people and situations. The whole is held together by a number of themes, one of which is the repeated return to an airport or transit hub.

This reminded me of another book (though this takes us back into fantasy); Changing Planes by Ursula K Le Guin. Unlike Flights, Changing Planes is specifically a book of short stories, in which the first story “Sita Dulip’s Method” sets the rest of the book up by explaining how the discomfort of waiting at an airport can, with a little effort, cause one to change from one “plane” of reality to another. To visit another world and live another life, while still being able to return in time to catch one’s plane.

Searching around I found an academic paper on the Liminality of the Lighthouse Image in Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse (PDF). The author of the essay makes a very good case for the Lighthouse performing the role of a liminal place in the novel.

In the Kitchen

I suspect one of the attractions for me in the idea of a liminal place is that it describes what I find myself doing as a writer. Here I sit on my kitchen chair, leaning on my table. I am holding my pen and scribbling a trail of ink across the paper of my notebook. I’m not in a corridor or an airport, not in a wood or a library – though I can imagine myself sitting to write in any of those places.

Yet this is a liminal place, because in my imagination I am travelling between realities and living in the skins of one character after another. It’s a metaphor for the writer. Insofar as all writers share this experience, perhaps all of us, regardless of whether we are writing fantasy, magical realism, or contributing to the literary canon, find ourselves repeatedly crossing back and forth over a liminal threshold. Fetching ideas home from the unconscious, the subliminal.

Too Long Didn’t Read – all the URLs

Author links go to the author’s home page or nearest equivalent where I can find one, where I can’t, the link is to their Wikipedia entry. Books link to their entry on GoodReads.

- Piranesi by Susanna Clarke

- The Divine Comedy (La Divina Commedia) by Dante Alighieri

- Changing Planes by Ursula K Le Guin

- The Midnight Library by Matt Haig

- The Magician’s Nephew by CS Lewis

- Flights (Bieguni) by Olga Tokarczuk

- To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf