[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/228270024″ params=”color=000033&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

I’m standing outside the town house of Victor Horta on a Sunday afternoon. Even though it’s a Sunday afternoon, there is a small crowd of us waiting to be let in. We’re waiting because the house is full of visitors and the Horta Museum has to limit numbers. It’s a small house and there are a lot of eager visitors.

Art Nouveau

I tried to visit last week, but the people running the house wanted me to leave my camera in the reception. As I wasn’t prepared to do that, I postponed my visit instead. Now I’m back – no camera, but I have my trusty recording device. Except I still haven’t learned how to use it properly and the 30 minutes or so of recording I made in the house is almost unusable. Oh well, better luck next time.

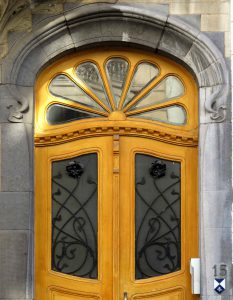

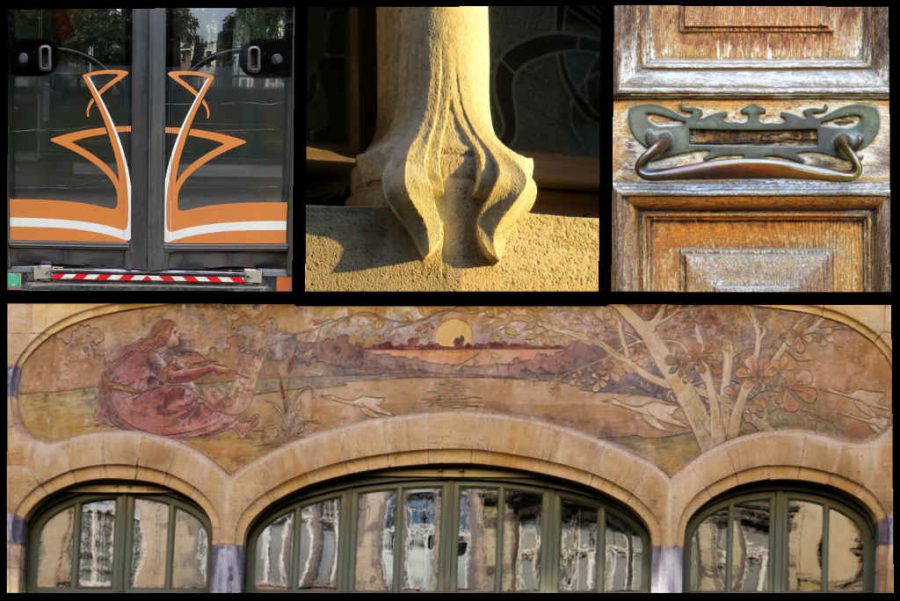

Art Nouveau (or, if you prefer, Jugendstil) – you cannot escape it in Brussels. It’s in the stained glass of door lights and window panels. It’s in the intricate ribbons of balcony railings. In the twisting forms of decorative house numbers and the willowy women featured in fresco facades. You even see it reproduced as graffiti, in the ironwork of some bus shelters and in the transfers decorating the doors of Brussels buses.

The man responsible for this – or at least the man who is credited with first introducing Art Nouveau into Brussels architecture – is Victor Horta. Whose town house I have just got into.

Excuse me while I pay the €8 entrance fee and buy a guidebook – €12.

Victor Horta

Victor Horta was born in 1861 into an artisanal-class family in Ghent. His father was a cobbler – a bespoke shoemaker perhaps, but still a working craftsman. The family must have had aspirations, though, and seen potential in their son. They paid for him first to attend music school to learn to play the violin. He was sent down for bad behaviour. Nothing daunted they tried again. The boy had once expressed an interest in building, so they paid for him to attend the Ghent Académie des Beaux-Arts to study architectural drawing. This time he behaved.

He completed his studies and, when he turned 17, left Ghent for Paris. Here he worked for an architect and designer in Montmartre. In Montmartre he was at the epicentre of modern art, and in 1878 in Paris he must have see the fantastic achievements of modern iron and glass technology on display at the Exposition Universelle. All of this would feed into his work and find an echo in his house. When he came to build it.

Horta’s house

The house and Horta’s office and studio were built on adjoining plots in 1898. Horta lived and worked here for 16 years until the Great War drove him from Belgium. When he returned after the war was over, he sold the house and studio separately. Both buildings then seem to have led mundane lives as middle-class homes until 1961 when the municipality of Saint-Gilles bought the house. In 1963 it became the first listed Art Nouveau building in Brussels. In 1969 the first incarnation of the Horta Museum opened here.

So, past the cash desk and leave the dining room on the right – it’s too full of people at present – and up the stairs to the first floor landing. This is an impressive space. The guidebook tells me it is equal in area to the space taken by the stairwell. It has windows opening on to the street at the front and no back wall separating it from the stairwell. The light from the street fills the space and reaches across to the dining room half a level down and at the back of the house. This space is made possible by using a iron frame – inspiration from the Paris Exhibition perhaps.

To one side are doors leading through to the reception room (with display cabinets) and Horta’s office – furnished now as a drawing room. The reception room and the office are in the studio, the building next door.

The Horta Museum

When the old studio came up for sale in 1971 it was also bought up by the Saint-Gilles municipality. In 1989 plans began to be laid to restore the two buildings and turn them into a single museum. Plans that – according to the guide book – “will be completed in 2014”. Well, it’s 2015 now and the restoration is clearly not complete, but it’s pretty good.

When the old studio came up for sale in 1971 it was also bought up by the Saint-Gilles municipality. In 1989 plans began to be laid to restore the two buildings and turn them into a single museum. Plans that – according to the guide book – “will be completed in 2014”. Well, it’s 2015 now and the restoration is clearly not complete, but it’s pretty good.

I suppose that while some people in Brussels are proud of Victor Horta and his works, other are less impressed – perhaps just because there is so much Art Nouveau (and faux Art Nouveau) in the city. In the same period that Saint-Gilles was buying the Horta home and creating the first Horta Museum, the city of Brussels was undergoing the same rush of modernized brutalism that London, Stockholm and other European cities were also enjoying. Out with the old, in with the new – especially if the new was utilitarian, concrete and dense. Notably, Horta’s first public space, the Maison du Peuple/Volkshuis (commissioned by the Belgian Workers’ Party and opened in 1899), was demolished in 1965.

But the dedicated and determined staff of the Horta Museum and the Amis du Musée Horta (founded 1982) carried on and gradually the tide seems to have turned in their favour.

Hidden urinal

Most of the furniture in the house appears to have been sourced from other places or collections. Little is original to the house, although they have managed to track down a few pieces. I suppose Victor Horta sold off most of the furniture, or took it with him in 1919, but I’m guessing he didn’t take the fitted wardrobes in the second floor dressing room. Off the dressing room are a bath (with gas fired boiler and shower) and a toilet. I’d like to believe they’re original too. Also, in the bedroom, the urinal hidden in a bedside cupboard.

One of the important influences on European Art Nouveau came from the English Arts and Crafts movement, and the Horta Museum includes wallpapers and furniture covering with a distinctly William Morris look about them. Another influence (and on the Arts and Crafts movement too) was oriental art. The house is decorated with wall hangings, prints and objects from China and Japan, as well as for example modern woven silk wall coverings made to Horta’s original design.

Simone’s quarters

Up the stairs again and we find the bedroom – suit really – designed for Horta’s only child, Simone. Her bedroom opens on to a roof terrace with views over the back garden and way across the roof-tops and gardens of the surrounding houses. The dressing room next door – also at the back of the house – has a sliding door that opens into a small greenhouse (with another door to the terrace).

This was the part of the house I most liked. Bright, light, green. I could live there. Across the stairwell at the front of the house is a guest room. Not bad, but not nearly as attractive.

The guidebook also describes the servants’ quarters. There is a separate servants’ staircase (which I glimpsed through one door left ajar), and there are kitchens and servants’ rooms too, but these were not open on my visit. Nor was Victor Horta’s studio with its high, wide windows which you can see from the street.

Hire the dining room!

It seems the Horta Museum has acquired the building on the other side of Horta’s residence – nothing to do with the architect – and is gutting it preparatory to moving the reception, cloak room and bookshop there – and perhaps adding a lift for disabled visitors. I can’t say, but it seems to involve work on the servants’ area as well. Maybe I’ll pay another visit next year and see how far they’ve come.

There’s a lot more to say about Victor Horta, but I think I’ll draw a line under this piece now. It was fun to visit the Horta Museum – even if I couldn’t see all of it – and I would recommend it to anyone with half an interest in architecture or Art Nouveau. Open Tuesday to Sunday inclusive (except for public holidays) 14.00-17.30. It takes about half an hour. The home page promises “Guided tours by appointment, booked one week in advance… [in] French, English, Dutch, German and, possibly, Italian and Swedish.” But when I asked, buying my ticket, I was told there are guided tours only in French and Dutch. I don’t know how to interpret that.

Apparently you can also hire the dining room for private dinners or cocktails for €2,500. Don’t all rush at once now!

I wrote this entry for the #Blogg52 challenge.

Väldigt väl beskrivet.

Vad roligt är höra dig läsa din text. Det gav en extra dimension till texten.

Tack Pernilla, Bra att du kunde höra det på telefonen – och att du tyckt om det.

🙂