It’s been nearly four weeks since I saw Alan Bennett’s The Habit of Art in a live broadcast from London’s National Theatre at the Bio Roy here in Gothenburg. I fully intended to write and record a review soon after, but circumstances dictated otherwise. I did manage to scribble down some notes, though, and before the experience quite evaporates from memory I thought I should at least attempt to say something.

The slipstream of Time’s chariot

Now, right there, “quite evaporates from memory”, that’s not good. I don’t want to suggest at all that the performance was ephemeral. It did stick in my memory, it made an impression. I enjoyed it a lot. But my memory isn’t as good as it used to be (as I like to think it used to be). Even powerful and engaging performances thin like smoke in the slipstream of Time’s wingéd chariot.

This preamble is appropriate in one way. The Habit of Art is about many things, and one of them is age and another is memory.

The premise of the play is that some time in the late 60s, the poet WH Auden and the composer Benjamin Britten meet in Oxford. Meet again, I should say, since they were creative partners before the Second World War. They collaborated on, among other things, The Night Mail, one of the early film documentaries. Auden, the elder, was the librettist. Britten, (in this retelling of the story) was in awe of his more famous companion. He felt shy, and as though he had to struggle to keep up his side of the partnership. But it was a productive and creative partnership nevertheless., resulting in several works.

The last of these was Britten’s opera John Bunyan. It was written at Auden’s suggestion specifically for an American audience and first performed in the USA where Auden was living. It flopped. Britten blamed Auden, and Auden accepted the blame. But Britten could never forgive him, and broke off all contact with the poet.

Grand Old Men

Apparently this was something Britten did. Old friends who had let him down in some way, he regarded as dead. For this reason, in later life, Britten and Auden never really did meet.

In this play, Alan Bennett supposes otherwise.

In Habit of Art, the elderly Auden has returned to England, to Oxford, as a Professor of English. He is respected as an icon, but disliked as a person. Disliked for his rudimentary personal hygiene, his behaviour (pissing in the sink), the fact that he employs rent boys for sex and his boring repetitive conversation at the college high table. He writes, because he has the habit of art, but produces nothing of interest.

Meanwhile, Britten who is similarly revered as a Grand Old Man, has also passed his prime. Young musicians now are inspired by other, younger, more daring composers. Britten they think is staid, predictable. In reaction to this, because he also has the habit of art, Britten is composing a new opera, based on Thomas Mann’s novella Death in Venice. It is not going well. People he trusts around him do not like the subject, though they go through the motions of helping him. The creative sparks do not fly. Britten is in Oxford to audition boys for the role of Tadzio. Though it’s been 25 years since they last saw one another, Britten takes the opportunity to seek Auden out at his lodgings.

A play within a play

The Habit of Art, though is not just a representation of this meeting. Instead it is a play within a play. The play in which Auden and Britten meet is being rehearsed in a rehearsal room at the National Theatre, with some of the actors, the stage manager and her assistant, the writer. This is the first run through. Not all the lines have been decided. The actors speak their lines in character, but also break out of character to argue with the writer and the stage manager. They complain about the absent director. Criticise and tease one another, discuss Auden, Britten, and Humphrey Carpenter (apparently the narrator of the Auden/Britten play).

This structure allows Bennett to stand back from the play, and to make fun of his characters. To laugh at the pretensions of actors and writers. To allow the compass of the play to go beyond poetry and music to include performance and play-writing. And to explore issues such as the creative process, aging, music, poetry, theatre, fame, homosexuality, loneliness.

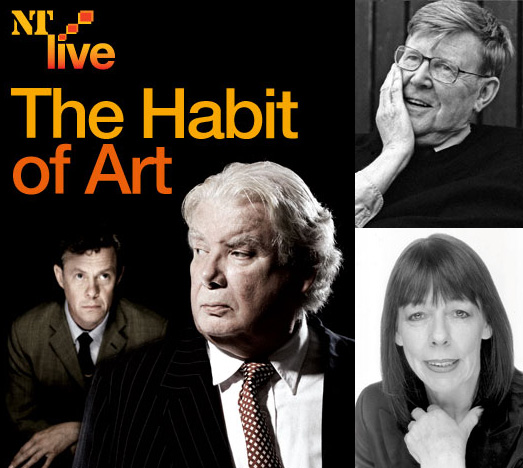

The roles, the actors

The actor who carries the biggest role in The Habit of Art, playing both Fitz and Fitz as Auden, is Richard Griffiths. He performed brilliantly and showed what a very good actor he is. Switching easily from the mannered enunciation of Auden to the more natural voice of Fitz. (Though Fitz – as an actor – can ham up his performance with accents too.) Fitz (though not Griffiths) is an actor past his prime, whose memory is a bit patchy and who nods off from time to time.

Playing the slightly effeminate Henry, the actor performing the role of prissy Britten, is Alex Jennings. As Britten, he seems to be trying to rediscover the fire of his youthful creativity. Re-building the bridges he has burned with Auden. At the same time proud of his achievements, and bitter and more than a little confused to find himself sitting on the establishment benches, sidelined by composers like Michael Tippet. The poisonous delivery of Tippet’s name sticks with me.

Self-worth

As Donald, the actor who is still trying to nail his performance as Henry Carpenter, Adrian Scarborough, projects a man who is trying to aggrandise his role. All of the three leading actors are competing for the limelight, but none more desperately than Donald, whose role is really not very significant. His performance after the interval, in drag and with a tuba, as “Doris of the Winds”, is the funniest part of second half. But it is also pitiful. Bennett is clearly having some fun with the cliché of the attention seeking actor. But he is also exploring another aspect of the same issue of self-worth that both the Auden and Britten characters are being forced to consider.

In this context, it is interesting to consider how these three well-known British actors are presented to their Swedish audience. The touchstone, I’m sorry to say, is film and, more particularly, Harry Potter. Richard Griffiths is “known to Swedish audiences as Harry Potter’s unpleasant uncle”. Adrian Scarborough is “Ron Weasly’s father from the Harry Potter films”. Alex Jennings, who doesn’t seem to have a Harry Potter credit (yet) is identified in our Swedish programme leaflet as “Prince Charles in The Queen“. He was good in that role, true, but he is better in this.

Kay switches off the lights

Frances de la Tour plays the role of Kay, the much tried stage manager. It is a wonderful performance. Her character’s efficiency and good nature, as well as the delight she takes in reading in for absent minor characters, are compelling. The scenes where Kay talks about actors and directors she has worked with – Richard Eyre, John Gielgud, Laurence Olivier – and about the National Theatre itself were so believable. The younger cast members listen with fascination. Actors entranced by the lore and the history of their own craft. Despite Bennett’s joking about actors and acting, he has a deep love for the craft and its performers. This wells up especially in Kay’s role.

At the end, Kay gets to switch off the lights and end the play, too. It was a nice touch, and I don’t know how Frances de la Tour did it, but in the simple action, and the pause just before, as she looks around the now empty stage, there is a wonderful feeling of contentment mixed with a kind of bitter-sweet longing.

Or maybe I was just reading too much into the scene.

What worked

Technically, this NT Live broadcast was very satisfactory. There was no sound delay (as in All’s Well that Ends Well) and the Lyttleton stage felt to be the right size for the performance and for the broadcast. It helped the atmosphere in Gothenburg that the cinema was filled, (though not to overflowing). There was a better turn out than for either All’s Well or Nation, about on a par with Phedre.

It was good to be able to hear the reactions of the audience in London. It helped cue reactions in Gothenburg. I’m sure most of the audience here were fluent users of English and a number will, like me, have been native speakers. But for the Swedes, even though the actors delivered their lines with clarity, it’s still a bit more of an effort. When one is used to subtitles one forgets how much of a crutch they are.

I think most people got most of the jokes. The only noticed our audience out of phase with London a couple of times. Once when Donald defends his character Humphrey Carpenter and stresses how he “practically started Radio”. That got a laugh in London but fell flat in Gothenburg. And then when Auden claims to once have been compared to a Swedish deckhand, that got a much bigger laugh here than in London.

What didn’t work?

Well, once again (as in All’s Well) there were several characters who were almost never picked up by the camera, apparently because they had little or nothing to say. This did not detract from the enjoyment of the play, but did raise a few eyebrows in the interval and on the way home. The Dresser? Oh yes, he had a line or two. The Chaperone? She sat at the back in the first act.

So, I come to the end and I realise my memory (with the help of my notes) is not so ropy after all. Of course, I’ve missed mentioning several of the other performers. I’m sorry, chaps, that’s the way of the world!

What more to say?

The introduction, the little conversation/interview in the open air on a balcony of the National with the Thames and the North Bank in view behind, is so much better now. The camera angles have been worked out and we don’t see interviewer looming over interviewee as in the very first broadcast. The little documentary info film about the real relationship between Auden and Britten was also appropriate, interesting and helpful.

I definitely want to see more, and I’m looking forward to the next season (and keeping my fingers crossed that Bio Roy will continue to show the broadcasts). I’m not sure about the extra broadcast, London Assurance, on the 28th June. The date might work for me, but I was very negative to some of the technical aspects of the previous broadcast from the cavernous Olivier stage. Still, it would be nice to see if those problems can be overcome – or if London Assurance is a more appropriate play for the stage. Maybe.

In the meantime, it’s time for me to wind this up with thanks to Alan Bennett, to the performers, to the backstage staff and to the broadcasters for a funny, witty, moving, engaging and very well acted play. Thumbs up!

Notes

The illustrations are all taken from the Internet site of the National Theatre.

I copied the pictures in the first illustration from the Production Gallery for The Habit of Art. Photographs by Johan Persson.

In the second the image to the left is reproduced from the programme. The two black and white portraits were taken from other pages on the NT site.

I simultaneously published a voice recording of this post, which is no longer available.