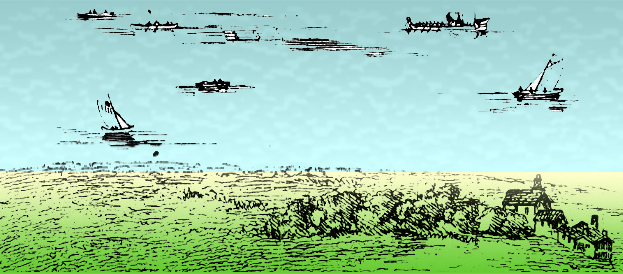

The river rippled in brown and grey: brown with silt, grey reflecting the sky. The early morning mist was retreating, little by little, as the day grew lighter, gradually revealing the banks of the river, the meadows and woods through which it wound, and first the outlines, then the more solid forms of the occasional cottage or landing stage for a grander house. Still, though, the mist hung in the air and the boat, travelling down the river, moved in a little world of its own in which the natural colours and sounds of the countryside through which it passed were muted, muffled. There was a promise of fine weather in the air, somewhere up above the enveloping mist, but not yet, not for some hours.

The oarsmen were skilled, and dipped and stroked with barely a splash. The boat cut a passage through the water with no more sound than a soft gurgle. When a startled duck flew up, surprised by the boat’s quiet approach, the alarm it made, its quacking and the whirr of its wings jarred sharply, though the sound was swallowed quickly enough as the duck vanished in the mist.

The noise woke the passengers who had all been nodding. None of them had enjoyed much sleep the night before, and warm beds and bedfellows were long ago and far away. Another country. They stirred and looked around, a little bemused before the memory returned of where they were and why.

The boat was a typical river craft, long, low and open. The boat-master at the tiller in the stern faced the four oarsmen who sat in the forward half of the boat, two by two pulling shoulder to shoulder. Between them, where the boat was broadest, the passengers sat under a frame for a canopy, but no cloths were hung on the frame and the passengers as much as the crew were exposed to the elements. The boat-master was a little troubled by this. It didn’t seem right. Not respectful. But there had been a rush to get launched in the darkest part of the night, so needs must. Not that they had had much to complain of as yet. The river mist had coated shirts and cloaks, hoods and hair with a fine silver dew, now evaporating, but there had been no rain as there so easily might have been this time of the year.

As the passengers slept and the light came up, the boat-master had watched them and speculated. There were four, two men and two women. The men sat one behind the other both facing forward. First, his broad back to the boat-master, was the one they had called Walter, he behaved like a manservant but carried himself like a soldier, his sword in its sheath was laid across his knees. Beyond him was the young gentleman, in his red travelling cloak and plumed hat, your typical court gallant, dressed for show. One of the Queen’s glorified messenger boys.

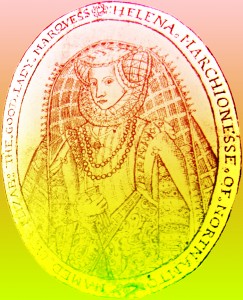

Opposite them, looking back up the river the way they had come so the boat-master could see their faces (and very attractive faces they were too, the master thought, if a bit too pale for his taste), the two women sat side by side. About the same age, in their mid-twenties. Asleep, they had leaned against one another. These two the master recognised under their hoods, the Lady Northampton and Mistress Browne her maid. He had ferried these ladies before. Once, indeed, he had carried them down to the Court at Greenwich where they had disembarked to be greeted by the Queen herself who embraced Lady Northampton and called her “My good Lady Marquis”. Of course there were others who called her “the German woman”.

Opposite them, looking back up the river the way they had come so the boat-master could see their faces (and very attractive faces they were too, the master thought, if a bit too pale for his taste), the two women sat side by side. About the same age, in their mid-twenties. Asleep, they had leaned against one another. These two the master recognised under their hoods, the Lady Northampton and Mistress Browne her maid. He had ferried these ladies before. Once, indeed, he had carried them down to the Court at Greenwich where they had disembarked to be greeted by the Queen herself who embraced Lady Northampton and called her “My good Lady Marquis”. Of course there were others who called her “the German woman”.

So why this rush so early in the morning, the boat-master wondered. Something’s happened that shouldn’t have happened, that’s clear. Did it have anything to do with the gallant? Is this an elopement? It didn’t feel like one (and the master had been involved in one or two of those as well).

It was frustrating not knowing who the men were. The boat-master prided himself on being able to recognise most of the hundreds of more permanent courtiers, it was an asset when ferrying for the palace, but there was a large crowd also of more irregular faces. He was sure he’d never seen the manservant before. Back from foreign parts, maybe, from the wars in Ireland or the Low Countries. There had been much coming and going recently. The gentleman, though, How many of these equerries were there after all? A couple of handfuls. The boat-master felt he really ought to know this one, but he’d not got a good look at the man’s face when they boarded in the flaring light of the torches and now all he could see was his back, and that was blocked by the shoulders of the soldier-servant. His manner on boarding had seemed bit querulous, reluctant. Still perhaps that was normal for gentry woken in the middle of the night and told off to escort ladies down the river.

The gentleman in question was also speculating. Geoffrey Morris was the youngest and most newly appointed of the Queen’s Gentlemen of the Court. He and his father had been angling and waiting and hoping for this place for months, years really, and he had been appointed now, only weeks before, to replace a man who had taken service with the Earl of Essex earlier in the month. This present task was his first independent responsibility, and he was already unhappy about it. He was uncomfortable on the hard bench, had not thought to bring a cushion, and he sat, knee-to-knee with the two women. If he stretched his legs, they would practically be sitting in his lap. Under other circumstances this enforced proximity would have been delightful, he told himself, delightful! And perhaps, when everything is over there will be a story here to tell, or a subject for a poem, but at present it’s just embarrassing.

God’s teeth, he thought. How did Gorges pull it off? And with the Marchioness of all the women at court! How much higher could you fly? Parr’s widow, the Queen’s uncle’s last wife! Morris himself had ambitions. Which Gentleman had not? The Queen’s Maids of Court were there, a half-dozen or so, fruit ripening on a bush just waiting to be picked, no, yearning, that was the word, and plucked, yearning to be plucked. But the Ladies-in-Waiting, well, Geoffrey wasn’t sure his own ambition stretched so far. Though, of course, now he couldn’t stop thinking about it.

Another river bird, a grey heron, flew overhead making for the reeds that concealed the southern bank. The maid turned her head to follow its flight, but the Marchioness sat gazing listlessly at the surface of the water.

She has a beautiful face, Geoffrey thought. That wide, smooth forehead with the strands of curling chestnut hair escaped from under her hood, those almond eyes, that child-like tip-tilted nose, that plump, so kissable lower lip, that …

To add to his discomfort, he realised he was getting an erection. He could feel his prick pressing up under his stylishly discreet codpiece. It wouldn’t be obvious to the women, surely, but he shifted on the bench, sat forward, crossed his legs, crossed his arms. He looked back at the Marchioness.

Though the boat rode smoothly, barely jerking with the strokes of the oars, still the woman looked sick. White in the face, but not fashionably alabaster. She was breathing in an unnatural way too, panting with her mouth a little open and swallowing. For a moment he thought of the whore from whose bed the man Walter had plucked him just hours before.

He shook his head angrily and embarrassed. No, no, don’t think that, he told himself. The woman looked up and caught his eye.

“My Lady?” Putting a note of concern into his voice, hoping she hadn’t read anything in his expression or the contortions of his body. “Do you feel unwell?”

“Yes, Master Morris.” She swallowed again. “It is ridiculous, but I feel seasick! Is there anything to drink?”

Geoffrey hesitated, unsure, then felt a hand on his shoulder. Walter, was handing him a flask.

“Malmsey,” he said.

Geoffrey took the flask and pulling out the stopper asked “Do you have a cup, my Lady?”

“Meg,” she said, turning to her companion who was already rummaging in a bag on the duckboards at her feet.

Morris handed the bottle to the maid who poured a small quantity of the contents into the pewter beaker she had found.

The lady sipped a little of the sweet wine. Swallowed. Closed her eyes a moment. He saw how her eyelids were almost translucent, how her eyes moved under them, how her long, dark lashes trembled. When she opened her eyes again, he was leaning forward, far too close, and found himself gazing into her eyes, into their brown-hazel depths flecked with gold. I could drown in those pools, he thought.

The eyes narrowed slightly and Geoffrey remembered himself, drew back. In disgrace she might be, but she surely still had powerful friends. Besides she was married again, and to that lucky whoreson, Gorges! How had he –. He shifted his gaze to the maid, and found her watching him too, and with a hostile expression. Feigning innocence, but feeling the blood in his cheeks, he took back the flask, stopped it up, passed it over his shoulder to Walter, then assiduously studied the north bank of the river where buildings were increasingly numerous and familiar.

The eyes narrowed slightly and Geoffrey remembered himself, drew back. In disgrace she might be, but she surely still had powerful friends. Besides she was married again, and to that lucky whoreson, Gorges! How had he –. He shifted his gaze to the maid, and found her watching him too, and with a hostile expression. Feigning innocence, but feeling the blood in his cheeks, he took back the flask, stopped it up, passed it over his shoulder to Walter, then assiduously studied the north bank of the river where buildings were increasingly numerous and familiar.

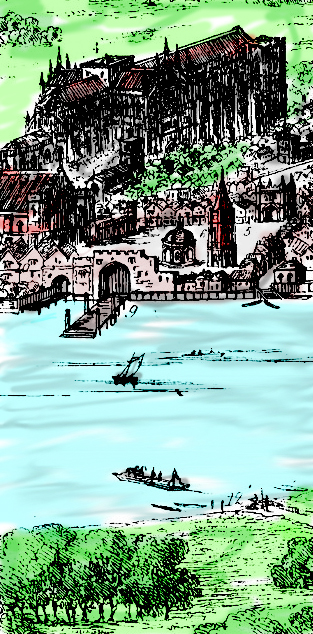

“Look,” he exclaimed, “Westminster Abbey!” As soon as the words were out of his mouth, he felt like a fool.

* * *

The surface of the river was becoming choppy now. The current, that had carried them down from above Richmond almost to Westminster, had turned and the oarsmen were having to strain more and more to keep up the pace. One of the oars caught the water at an unexpected angle and there was a splat.

“Gently lads!” The boat-master called out.

There was more noise now, splashes and cries, and more traffic. As the water level rose, flooding the mudflats on either side, more and more rowing boats, large and small, were putting out from the jetties and steps of the north bank. A steadily increasing stream of vessels were ferrying passengers east and west between Westminster and the City. In amongst these, unwieldy, flat-bottomed barges, stacked with barrels or bales were rowed by men standing to pull at stern paddles. There was even some cross-river traffic and a few sailing skiffs. Off the south bank, anglers sat in their little boats, one man alone or a couple together.

For all the buildings, grand and less so, on the north bank (and now they were passing the Whitehall Palace with the Savoy coming up and Somerset House beyond that), the south bank was still countryside. Lambeth Marsh, only partly drained, where herons still fished among the reeds and eel and flounder, gudgeon and lamprey could be had by those who knew where to trail their baited lines.

“How much further?” asked the Marchioness

“Nearly there, my Lady,” said the boat-master, just as Geoffrey Morris pointed and said “There are the White Friars steps.”

The master took the boat a few lengths past the place where Morris pointed, then, at his command, “Sweetly lads!” the rowers on the starboard side shipped their oars, the boat swung around and the incoming current carried them back smoothly alongside the wooden steps.

One of the oarsmen was already standing to leap ashore with a line from the bows, while the master tossed the stern line, uncoiling as it flew, to an ox of a man loitering on the steps who caught it expertly. With the boat tight against the side, the passengers could disembark.

The soldier-manservant was first off and the boat-master noticed with approval how he jumped, how sure-footed he landed. Could be a sailor, thought the master, and saw how the man’s blade now hung easily at his hip. One-handed, he took a bag the maid passed him and hoist it ashore, helped the gentleman to land, then spoke to the big man who had been standing on the steps, engaging him apparently as a porter. There were two bags more and a small chest to offload, and then the ladies to hand up.

Geoffrey stood on the steps, brushing at his sleeve. One of the oars had splashed him when it shipped. Suddenly he realised everyone was looking at him and the boat-master was holding out a hand. So he had to pay as well? Not with the best grace, he found coin in the purse at his belt.

* * *

The crew aboard again, the boat cast off. The master and his men were keen to catch what remained of the incoming tide back to their station (and a late breakfast) at the Palace of Whitehall.

When they reached the Whitehall Steps, however, as though by chance they were engaged directly by a well-dressed foreign gentleman for a short trip on up-river to Westminster. The man spoke excellent English and cheerfully volunteered his business, the son of a wealthy Flanders merchant, visiting England to learn his father’s trade. He was generous with his money too, not like the court dandy in the previous party. When he learned the oarsmen had not eaten since before dawn, he bought the crew a big trencher of cold meats and jugs of ale all round at the King’s Bridge.

Later in the day, the information the generous gentleman had gleaned, combined with news from other sources, made its way as a footnote into a letter from the Spanish Ambassador, Antonio De Guaras to his master the King of Spain.

Further: this day at daybreak Lady Helena, Marchioness Northampton, was conveyed down the river by one Morris, a courtier, and a soldier. She is in disgrace. Her unsanctioned marriage to the Queen’s Gentleman Thomas Gorges is discovered. She is to be held at the Queen’s pleasure in the house of the said Gorges (and at his expense) in the White Friars. It is not known where Gorges is held, but some say the Tower.

‘September 1576’

Calendar of State Papers, Spain (Simancas)

Volume 2: 1568-1579.

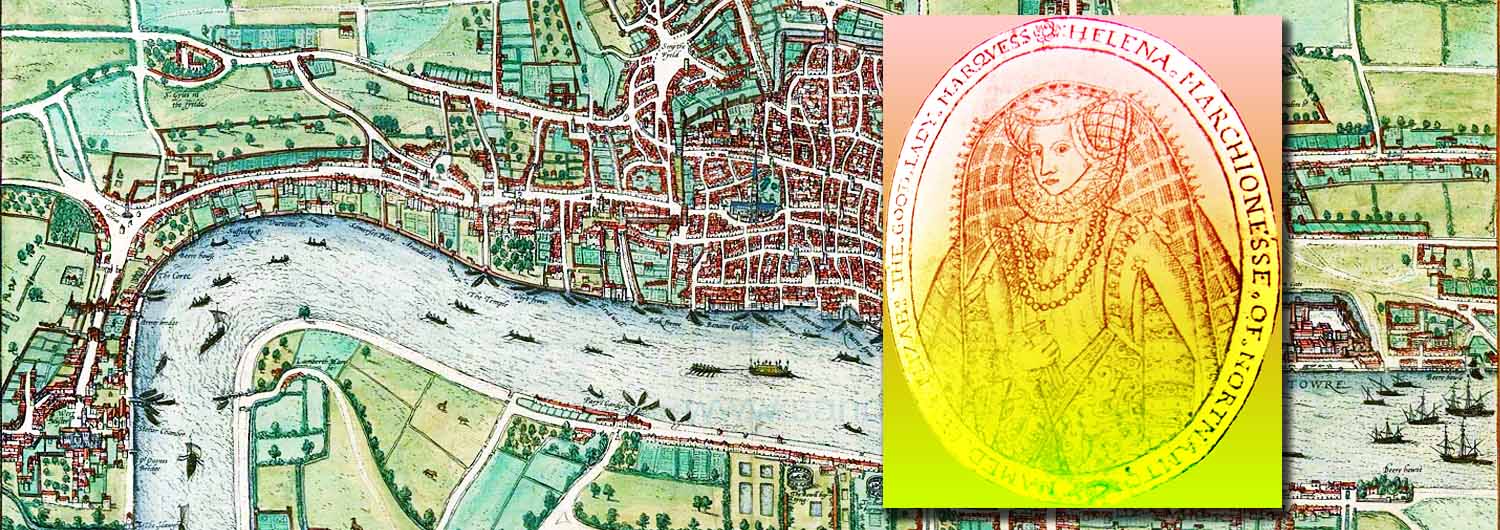

For those as wants to know, the portrait of Helena, Marchioness Northampton comes from an illustration described as “contemporary” and from the Lansdowne Roll 8 in the British Museum, reproduced by Charles Angell Bradford in Helena Marchioness Northampton in 1936. The source of all the other illos is the map of London made some time in the mid 1500s and published in the Civitates Orbis Terrarum by Georg Braun and Joris Hoefnagel in the early 1570s.