Cosmonauts – sailors through the cosmos; astronauts – sailors among the stars.

That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.

We’re all going on a summer holiday

It was the summer of 1969 and I was nearly 11. My family – my mum, my grandmother, my kid sister and I – were on our way north. We were going to stay for a week in the English Lake District. Mum had rented a cottage by Lake Windermere, but it was a longer journey then, all the way from Brighton to Cumberland. We were breaking our journey at a hotel in London.

We couldn’t afford it, but Grandma’s youngest brother was currently in funds and he’d rented the room for us. It was palatial. There were beds for all of us, an en suite bathroom and a mini-bar with chocolate. (There may have been other things, but I remember the chocolate.) Most impressively – and importantly – there was a TV. This night was the night of the Apollo 11 moon landing, this evening a man – two men – would walk on the moon for the first time, and the whole event would be broadcast live.

Astronauts

I think everyone in the family was interested – it wasn’t just that I’d been talking of nothing else for days – but each person was interested to a different degree. We were all awake when the Eagle separated from the mother craft and I know Mum, at least, was still awake when Eagle landed at Tranquility Base at a quarter past 9 in the evening. At 3:56 in the morning, though. I was the only witness to Neil Armstrong’s hop down onto the moon’s surface and his words.

Of course he should have said “one small step for A man”. That’s what he’d rehearsed, but he fluffed it. Not that it mattered. Not that I or almost anyone else noticed at the time.

Amazing to think the Soviet Union had come so close to beating the Americans.

Cosmonauts

In 1989, twenty years after the Apollo 11 moon landing, the secret came out. The Soviet Union had its own moon programme and its own moon lander. The plan was to reach the moon before the Americans. It would be a propaganda triumph in the same style as putting Sputnik, the first satellite, into orbit, or Laika, the first dog in space, or launching Gagarin and Tereshkova, the first male and first female cosmonauts, into space and safely bringing them back down.

The Soviet programme, like the American, had its disasters but they were hidden away and never openly discussed. Failure was not deemed acceptable. Sending someone to the moon had to be done successfully and in public, or not at all. If it was public and it failed, the propaganda effect would be disastrous. In the end the technology was deemed unsafe. There was no way to guarantee a successful landing and successful return. The programme limped along for a few years into the 1970s but was eventually abandoned and classified as top secret.

Birth of the Space Age

That was then. Now one of the never used Soviet lunar landers, the LK-3, is on display as the key exhibit of Cosmonauts: Birth of the Space Age, an exhibition about the Soviet space programme showing at the Science Museum in London. The exhibition runs through to mid-March 2016 – after which I guess it will travel on to other places. I hope it does, though with the state of political tension that exists between Russia and the West, who knows. It’s a small miracle that it’s taking place at all, though I suppose given the time necessary to set up an exhibition of this sort it, was probably conceived and approved long before tensions got so bad.

And, of course, the space programme continues to be one conspicuous area of co-operation set aside from politics. No doubt because everyone has more to gain from keeping it so. The BBC has recently been following the adventures of Britain’s latest astronaut, Tim Peake, to the International Space Station. He was launched from the Baikonur Cosmodrome, the old Soviet launch pad and the only one in the world that can currently put people into space.

Cosmonauts and astronauts

When I was 11, I wanted to be an astronaut. I wasn’t alone, I’m sure of that. Wandering around the Cosmonauts exhibition, as I did when I was in London in October, I overheard many an older gentleman of my generation (and one or two ladies too) steering grandchildren around and reading aloud, in hushed and reverent tones, the signs on the exhibits. Sputnik and Soyuz, Gagarin and Tereshkova. Let’s not forget, these were our heroes and our inspirations too – along with Eagle and Apollo, Armstrong and Aldrin.

Some at least of the kids seemed interested.

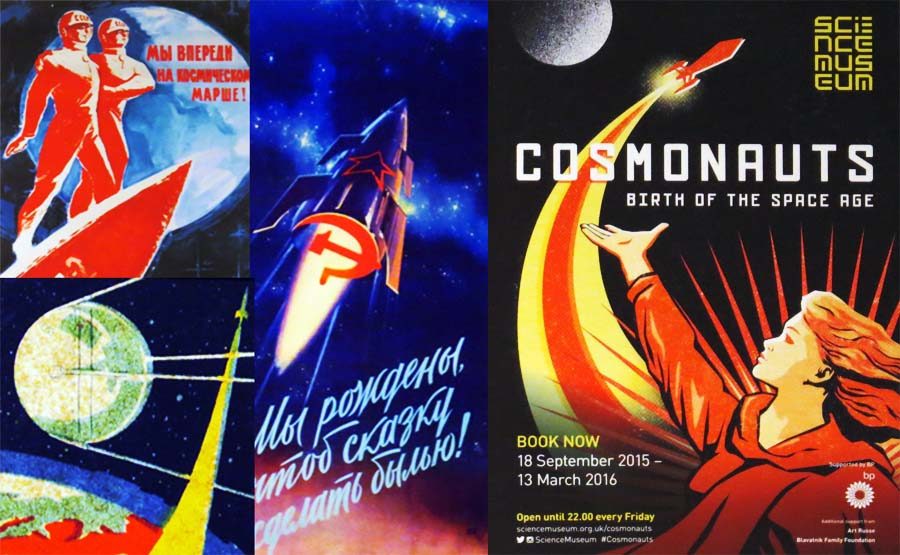

The illustration at the head and foot of this article is a collage of Soviet era space-race posters, together with the poster advertising the Cosmonauts exhibition at the Science Museum. They are all clipped out of photos I took of the posters on sale in the Science Museum’s shop.

This article was written for the #Blogg52 challenge.

I originally published this article on the separate Stops and Stories website. I revised it for spelling punctuation, carried out some SEO fine-tuning, and added a featured image before transferring it here on 6th April 2017.

It is strange how allt the names of the astrouanuts and cosmonauts awakens memories. I wonder if it is the same for young people today and I think maybe not. They have so much more information and news. Laika makes me sad, her death cannot have been a pleasant one. But part from that it was fantastic times with a feeling of future and no limits.

I guess kids today have other heroes whose names they will react to in the same way we react to these. But they are probably not astro/cosmonauts (although Chris Hadfield’s version of “Space Oddity” may attract some).

https://youtu.be/KaOC9danxNo

As for Laika, the exhibition made very much of what happened when they shot her up, but very little of what happened to her afterwards. And the shop was selling lots of stuffed toy Laikas in space suits, which I thought was in rather bad taste.