In which we consider the actual author and the reader, both the author’s imagined reader and the actual reader, and consider the gaps between them.

Who is your ideal reader?

Who do you write for? Who is your ideal reader? The minimal research I carried out for this article suggests these are questions that crop up repeatedly in the opening stages of creative writing courses. The same questions, or questions like them, are the jumping off point for many a blog post.

I also see that most answers fall into one of two camps.

On the one hand are the answers that broadly or narrowly define the reader the writer has in mind. I’ve seen writers claim to write for readers who are “young adults between 15 and 21,” “fantasy and role-playing fans of both genders and none,” “military history buffs,” “lovers of the Golden age detective story.” And so on.

On the other hand are the answers that try to avoid the question. “I write for myself,” seems the most common.

The former response is helpful, no doubt, especially if one is writing within a genre or writing commercially, but I can imagine it could also be crippling. What do you do when you run into an issue or a situation, or dream up a character, that doesn’t fit into the straitjacket of your projected reader? Doesn’t it hurt?

At the same time the “write for myself” answer feels like it might be ducking the question. Maybe you are writing for yourself because you are the only person who can appreciate your genius. The only person who can understand. Which implies that your writing is not intended to actually communicate anything to anyone outside yourself. Perhaps, in fact, you can’t communicate in writing with anyone else. Perhaps you’re just not a very good writer.

Slightly out of phase

It seems to me that we all do have an idea of an audience when we write, and that audience is not ourselves. At least, not ourselves as we are now, writing whatever we write. We might try to write for the person we once were – to write the sort of books we’d have liked to read when we were younger. We might write to communicate with our future selves (in a private journal perhaps).

For me, the closest I come to writing for myself today is when I am writing in order to work out what I think about a subject. I find it easier to understand something if I explain it to myself in writing. I’m not sure if this is the consequence of having been a teacher. It may be an innate tendency which contributed to getting me into the teaching profession in the first place.

But even in that situation, my imagined reader must be someone slightly different from myself. Slightly out of phase. It must be a version of myself who still doesn’t understand what my writer-self has worked out enough to try to explain. Or a future self who has forgotten.

Actual Author and Implied Reader

I fell down this particular rabbit hole after reading Philip Pullman’s Daemon Voices. Specifically the “afternoon session” of the essay “God and Dust: Notes for a study day with the Bishop of Oxford”. This is the essay where Pullman presents the different writers and readers involved when someone reads a text. He identifies five: the actual reader, the implied reader, the narrator, the inferred author and the actual author. I’m only going to take up the first two and the last one here. Quite sufficient for one blog post.

(That minimal research I mentioned above turned up a small additional collection which I also won’t go into. The Living Handbook of Narratology on the website of the University of Hamburg, for example, distinguishes between the “Implied Reader as Presumed Addressee and Ideal Recipient” and the “Implied Reader as Presumed Addressee vs. Fictive Addressee”.)

The Actual Author is the person writing the text at the moment they are writing. I am the Actual Author of this text as I tap out these letters on my keyboard. Who am I writing for? Why, I am writing for you, my dear Implied Reader (presumed addressee and ideal recipient). That is, I am writing for the reader I imagine myself to be writing for. Whether that’s a young adult fantasy roll-playing lover of Golden Age detective stories, or my near future self. (I lean towards the latter.)

Implied Reader and Actual Reader

However, my Implied Reader is not the same as my Actual Reader. Whoever I think I’m writing for, however I imagine you to be, I really have no idea who you are. You may match the idea I have of my reader, but it’s more likely you are quite different.

And does that matter? If I write for a young adult fantasy role-player of unspecified gender, how disappointed would I be to discover my most avid reader is a middle-aged cis-male shop assistant who’s never taken part in a role-playing game and wouldn’t know how to begin? As long as he keeps on reading.

Hans Hirschi is a writer of LGBTQ+ fiction who I got to know when our brief memberships in a Swedish indie author group overlapped. He told me once that the biggest audience for his “inspiring feel-good fiction with unconventional, but always hopeful or happy endings” were middle-aged heterosexual women. I think he was surprised to learn that.

Actual Author and Actual Reader

I never asked Hans if knowing about his Actual Readers made a difference to the image he had of the reader he was writing for while he was writing. I doubt it. Or if it did, I don’t think it would have caused him to change his writing. But I can well imagine there might be a temptation for others.

There might even be pressure from a publishing house or an agent if the Actual Author was signed to one. “Appeal more to this reader,” they might say. “Attract more of them. Sell more books.” And that might work. But it might also capsize the whole enterprise, since what attracted these Actual Readers to the Actual Author’s writing was clearly not that the author was pandering to them in the first place.

Speaking personally, as long as I’ve got some Actual Readers – any Actual Readers – I’m happy.

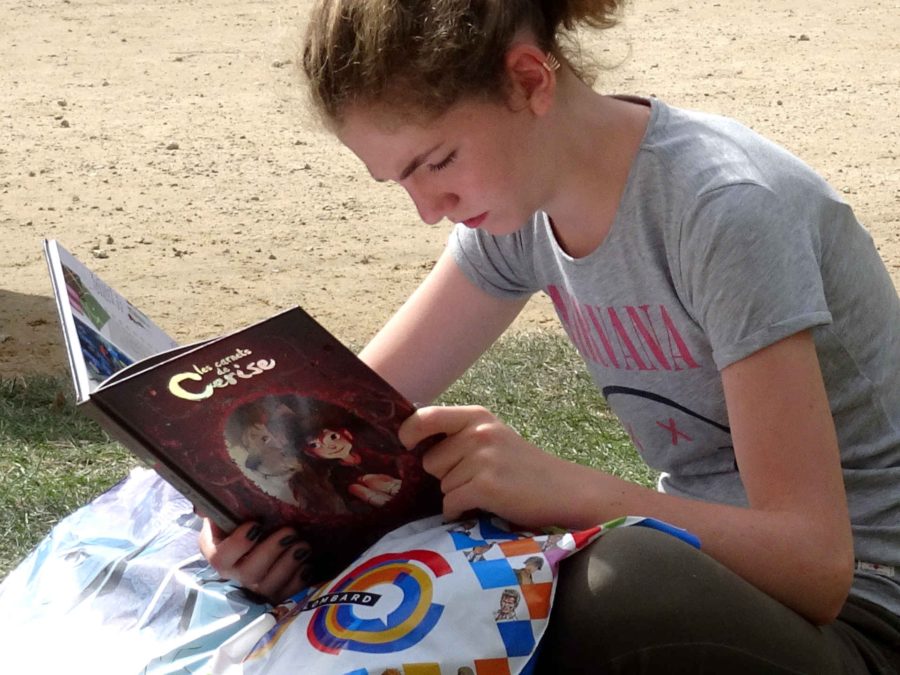

A note about the illustrations

The photo of the Actual Reader (in all probability not an actual reader of TheSupercargo.com) was one I took at the Belgian Comic Strip Festival in September 2016. The picture of the Actual Author comes from a post about my 2020 Writing Goals, though I think the photo itself may be from brighter, warmer days in 2019.

Thanks for the mention. I can inform you and your esteemed readers that knowledge of my readership has indeed changed my writing, in more than one way. And not the way you’d imagine or the way I had suspected it might. And it still does. Sadly?!

Thanks for stopping by Hans. What you write is intriguing. Care to elaborate?