I often read books in parallel. I like the heat that friction between different books can generate. Sometimes the friction will tear open gaps in the fabric, letting the light from one book illuminate events in another. Over the last half of July and into the beginning of August, I’ve been reading This Much Huxley Knows by Gail Aldwin, Kalla det vad fan du vill by Marjaneh Bakhtiari and Love in a Cold Climate by Nancy Mitford.

Comedies of Manners

Apart from sharing space on my bedside table, what do they have in common? They are all funny, each in its own way, and a pleasure to read. Gently humorous or bitingly satirical, they are all about young people, their families, and the societies in which they are embedded. In contemporary suburban England, seven year old Huxley uses wordplay to cope with bullying, in and out of school. In late 20th century Malmö, teenage Bahar rebels against her immigrant family and Swedish society generally. And among English aristocrats in the 1920s, nineteen year old Polly extricates herself from the grip of her controlling mother by arranging her own marriage.

I’ve been looking for a single literary term to cover these three. The best I can come up with is “comedy of manners”. A comedy of manners is a book (or a stage play, or a film) in which the story is less important than the world depicted. Comedies of manners are often humorous, often satirical, but always focus on the minutia of events and characters, and the social context in which the events and characters are set.

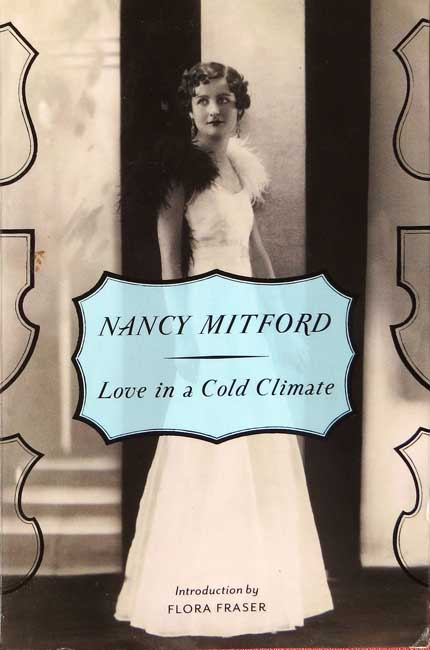

Love in a Cold Climate

Of the three, Nancy Mitford’s Love in a Cold Climate is the one which comes closest to being a true comedy of manners. Polly’s upper-class English family is observed by a young woman, Fanny, who is not of quite of the same social class though close enough to be an accepted presence. Someone who is endowed with protective colouring … I might just as well not have been there at all, and could keep happily to myself and observe their antics. … It was my place to be seen and not heard.

What Fanny sees and hears is the ritualised dance of social interaction between members of the British aristocracy prior to the Second World War. References in the book date the events to the late 1920s, although the book was actually written and published in 1949. Lord and Lady Montdore’s 19-year-old only child, Polly, is a debutant. Her mother seeks to marry her well and exhibits her on the marriage circuit, something the girl does not enjoy. Polly chooses the path of teenage rebellion by proposing marriage herself to Boy Dugdale, a man of Fanny’s parents’ generation. (He went to school with her uncle.) Boy also used to be the lover of Polly’s mother.

Cedric

Polly, as a woman, cannot inherit the Montdore estate or title after her father. These must go to a male heir; distant cousin, Cedric, born in Canada but now living in Paris. Cedric turns up in England halfway through the novel as a human dragonfly … A tall thin young man, supple as a girl, dressed in rather a bright blue suit, … flashing a smile of unearthly perfection. He is, as Fanny’s Uncle Matthew says, one of those aesthetes, you know – those awful effeminate creatures – pansies. In modern parlance, he is gay.

Cedric wows both Lady Montdore and Boy Dugdale, while Polly ends up in effect as mistress of her own destiny. Respectably married, but free from both her mother and her elderly husband, both of whom Cedric has taken over from her.

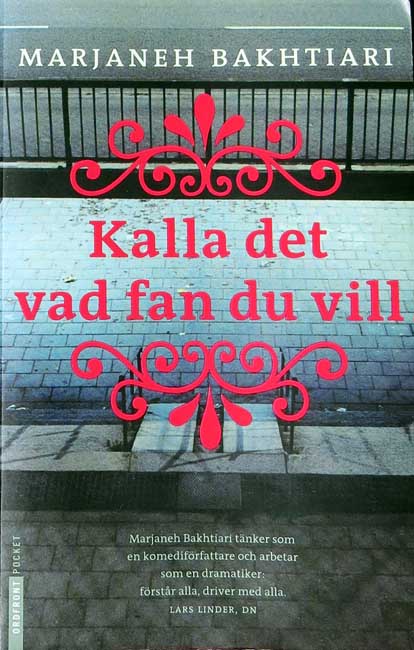

Call It What the Hell You Like

Marjaneh Bakhtiari’s Kalla det vad fan du vill (more or less Call It What the Hell You Like) is also the depiction of a social class largely through the lens of a single family. The Irandousts, Amir and Panthea, are Iranian immigrants to Sweden. As in Nancy Mitford’s book, there is no very clearly stated time span, but internal evidence suggests most of the action takes place in the late 1980s and early 90s.

Amir and Panthea bring their young children with them to Sweden. The parents make the move, they tell one another, to give their children a better chance in life. At home in Iran Amir was a respected publisher while Panthea was a university research physicist. In Sweden they find themselves simply immigrants, one family among many. Early on, it is their daughter Bahar, and then Shervin their son, who must act as their interpreters. Later, Amir works in a video store, becomes a self-employed pizza baker, and finally ends up as a taxi driver. Panthea becomes a kindergarten teaching assistant. A steep fall from middle-class, academic respectability.

Kaleidoscopic narrative

The narrative of the book winds its way around the Irandousts, their children, their friends and acquaintances. Bahar is often the principle character, determined, stubborn, angry with a burning desire to see moral justice, but uncertain what moral justice might be. The account embraces the family of Bahar’s Swedish boyfriend Markus and especially his racist, socialist grandfather Bertil. It takes in Jamaican Moses and his Chilean refugee girlfriend Rosa. It includes Shervin’s friends Cezar and Soroush, Soroush’s family, and mythomaniac Mirza. It extends to Amir’s old friend Bijan, his failure to help his sister and her family escape to safety, which results in him taking his own life in despair.

The novel doesn’t get anywhere. Most of the characters are much the same at the end as they were at the beginning, although there are signs that Amir, Panthea and Bahar at least have grown during the course of the book. There is no overarching development. And this is what I think puts the book into the comedy of manners category. It’s an entertaining read, especially if you can hear the melody of the spoken word in Bakhtiari’s rendering of Iranian-fractured Swedish, Skånsk dialect, Jamaican patois as the different characters speak. There are many small stories that build up into a kaleidoscopic picture of the immigrant experience in Sweden.

There’s no grand design, no cathartic resolution, and perhaps there can’t be. I presume that Marjaneh Bakhtiari is, like Bahar, a child of Iranian parents brought up in southern Sweden. Perhaps there will be another novel, written by another generation, that will be able to show a resolution. In the meantime this is a brilliant, tragicomic picture of a social situation that is painfully familiar.

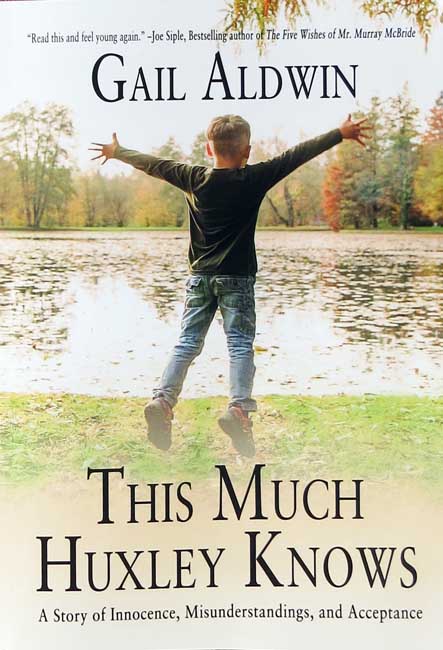

This Much Huxley Knows

The newest of my three books is Gail Aldwin’s This Much Huxley Knows. It is told from the perspective of seven year old Huxley Griffiths, somewhere in contemporary suburban England. On the surface, it’s a simple story from one autumn school term in Huxley’s life. It starts somewhere in September and ends at Christmas. But it packs in a lot. There’s humour, morality, confusion, sex (at least some talk of it), some gentle satire, and at times quite a sad picture of current British behaviour and concerns. Brexit is a topic, an irritation and an opportunity for Huxley to demonstrate how he plays with words. In his mind Brexit sounds like “breaks-it”, which also describes how it affects his world.

Huxley is an only child and, at least at times, a lonely child. In his second year of primary school, he doesn’t have any “mates”. He doesn’t like football, which means his best friend out of school, Ben (who loves football) doesn’t want to play with him in school. Huxley is a bully’s mark. In particular his classmate Zac has it in for him.

Huxley tries to escape from this, and from feeling alone, by playing around and especially playing with words. He knows some long and quite complex words because he breaks them down into funny syllables (“silly-balls”). Some kids, and a few adults, appreciate his humour. Rather more either don’t get the joke or think he’s being silly. (His schoolteacher, Mrs Ward, is particularly unimpressed by his reinterpretation of school assembly as “arse-hem-play” and “ass-embly”.)

Bullying is wrong

Bullying, picking on others, ganging up is one theme that runs through the book. Not only does Huxley have to contend with it in school, but there is a gang of secondary school children causing trouble which escalates through the book. The most disturbing thing, I found, was the behaviour of the adults around Huxley. They tell Huxley that bullying is wrong, but they are just as prone to it as the secondary school kids. Indeed, they condone the bullying, and even join in, when it is directed against someone the parents have convinced themselves is a paedophile.

Fortunately, by the end of the book, the adults have come to their senses and their prejudices are shown to be unfounded. Huxley finds a new friend in his classmate Samira (who may be Iranian), and Zac, Huxley’s personal bully, buries the hatchet after Huxley demonstrates that he can do something physically Zac can’t. (Even if it isn’t kick a ball.)

Consistency

One of the most impressive things about This Much Huxley Knows is the consistency with which Gail Aldwin keeps to Huxley’s point of view. There are many things in the book that Huxley doesn’t know, things he misinterprets; but the reader understands what’s going on. For example that Huxley’s father, Jed, and Ben’s father, Tony, are in competition with one another. Or that Huxley’s mother, Kirsty, and Lucy the Sunday school teacher, are friends of necessity, despite Lucy’s flirting with Jed.

But the greatest achievement, I think, is the characterisation of Huxley. The front cover picture of a little boy leaping into the air with his arms, hands, fingers outstretched, is wonderfully appropriate. I don’t know if this is how seven year old boys are, but Gail’s writing has convinced me this is how they can be. This is how Huxley is.

To Long, Didn’t Read – the direct links

Book links go to the appropriate Good Reads page, author links to the author’s website in the first instance, then to a publisher’s website for the author, or to the author’s Wikipedia entry if there is one.

- This Much Huxley Knows – Gail Aldwin

- Kalla det vad fan du vill – Marianeh Bakhtiari

- Love in a Cold Climate – Nancy Mitford