Sometimes when I’m stuck for a story idea, I revisit a series of books I enjoyed as a child. (Also, it seems, when I’m stuck for a blog entry.) The books are the stories of Dr Dolittle and his “family” of animal friends – and the occasional human

Stories in your pocket

In several places in the books when the doctor and his “family” are killing time, someone is sure to ask the doctor for a story. His usual response is that he can’t think of one, but then turns out his pockets. His pockets are full of all sorts of things that he’s picked up here and there over time and there’s always something he can tell a story about.

It’s a good technique, and you don’t have to fill your pockets with odds and ends. Just look around and let your eye light on something. If you’re at home you might look at the pictures on your walls or the things on your shelves. You might look at the furniture or animals in your room, or what you can see out of the window. If you’re out, look at the people passing by or the decorations on the buildings. Or you can try to be extra aware of adverts, snatches of conversation, smells, insects, rubbish.

Ask yourself, Does thing this have a story to tell me? Why does it look this way? Who used it? Who threw it away and why? Or did they drop it – is it lost? Who is this person? Where is she going and how do I know?

I’ve even used this technique when I’ve been teaching English conversation as a hook to start people talking. Getting them telling stories about themselves or their surroundings.

Dr Dolittle and the Great War

If you search for Dr Dolittle on the Internet, as I’ve just done, the majority of the hits you get take you to the Eddie Murphy films from the turn of the recent century. Or to the 1967 Disney film with Rex Harrison as the doctor. But Dr Dolittle is much older than that. Hugh Lofting wrote the germ of his Dr Dolittle stories in letters to his children from trenches and battlefields of the First World War. Of all the writing to come out of that terrible conflict, the Dr Dolittle stories were surely the most unlikely.

Hugh Lofting was British but married and resident in the USA when the war broke out. In 1916 he was called up, travelled back to Britain and saw service on the Western Front in 1917 and 1918. His experiences in the trenches were, he said, by turns too horrible or too boring to put into letters home to his young family. His daughter was four years old in 1917, his son just two. Besides, his children wanted stories and pictures.

Animal conscripts

Lofting looked around and his eye lit on the animals conscripted to fight in the war alongside the humans. Years later he wrote:

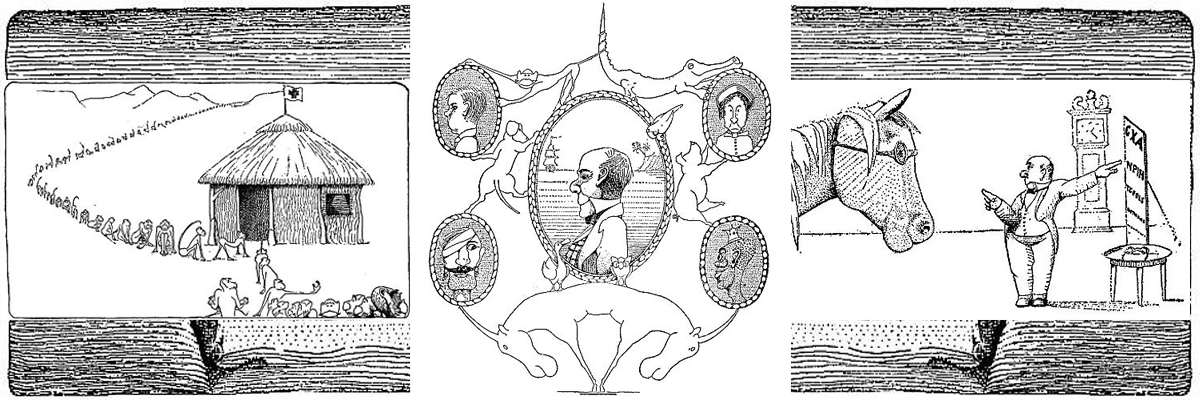

If we made the animals take the same chances we did ourselves, why did we not give them similar attention when wounded? But obviously to develop a horse-surgery as good as that of our Casualty Clearing Stations would necessitate a knowledge of horse language.

And so the idea came to him of a country doctor, disillusioned with human society, who prefers the company of animals and who learns to speak with them in order to be able to take care of them.

The letters written 1917 to 1918 became the basis for Lofting’s first novel The Story of Dr Dolittle. Or, to give it its full title, The Story of Doctor Dolittle: Being the History of His Peculiar Life at Home and Astonishing Adventures in Foreign Parts Never Before Printed.

This article was written for the #Blogg52 challenge.

The illustrations are by Hugh Lofting and taken from Dr Dolittle’s Post Office and The Story of Dr Dolittle. Hugh Lofting died in 1947, so his works are under copyright in Europe for another two years. The book is out of copyright in the USA, though, as it was published in 1923. These illustrations come from digitized versions of the books held in Canada. If anyone from the Estate of Hugh Lofting objects to my using these illustrations, please get in touch and I will remove them. But I hope you won’t.

I originally published this article on the separate At the Quill website. I resourced the illustrations,revised the article for spelling and punctuation, carried out some SEO fine-tuning, and added the featured image before transferring it here on 13 April 2017.

Very interesting! I have only seen the films (both Rex Harrisson and Eddie Murphy), never read the book. Now when I hear the background I really admire the author. Wonder why he is not in our litterature at school, about how to write?

Thanks for your comment Eva.

I think I know why Doctor Dolittle may not have been a success in Sweden even though the Swedish language Wikipedia has a “stub” about Lofting and mentions that at least the first book was translated not less than five times – most recently in 1978. However, as with so many books from the period, there is an undercurrent of racism in some of what Lofting wrote – and more than an undercurrent in some of his illustrations. (Think: Astrid Lindgren, Pippi, neggerkungen and multiply that by some number.) I don’t think he was racist, but I think he reflected the perceptions of his day in a way that hasn’t been acceptable for 50 years or more. Probably longer in Sweden. I note that the two later Swedish translations were not of Lofting’s original text and had illustrations by another artist.

As for the story creating idea, I don’t think it’s central to the books (though I suspect it’s exactly how Lofting went about inventing his stories). It’s just that it stuck in my memory.

Mycket intressant läsning, som vanligt! Tänk, jag tror aldrig jag har läst Doktor Dolitte, bara sett filmen. Nu blev jag intresserad av att läsa boken!

Kram Kim 🙂