As I wrote the other week, in March Mrs SC and I were in London. Our first visit abroad since the Coming of the Plague. We were only there for a couple of days before travelling on to Northampton for my mother’s birthday. In London we stayed in Bloomsbury. Wanting to make the most of our time, the evening of the day we arrived we took a walk around the district. And found the Foundling Museum.

The Foundling Museum

The Foundling Hospital is one of those places you may read about, often in different contexts, but which you somehow never associate with a real place. At least, that’s me. Seeing the words Foundling Museum on a sign outside a rather nice faux Georgian building tucked behind a fenced-off park, along what we thought was a dead-end street was unexpected. The familiarity of the name was a surprise. My associations: William Hogarth, Handel, Charles Dickens, orphan children, but I couldn’t put them together.

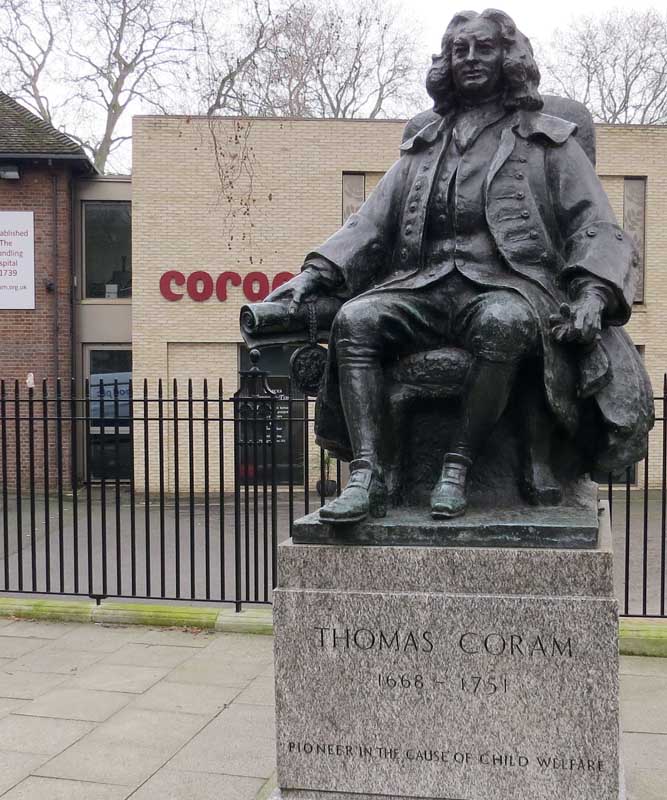

The light was failing and the building was shut. Nearby, a friendly looking gent in britches and a frock coat sat on his chair on a plinth. Cut in the stone: Thomas Coram 1668-1751, pioneer of child welfare. On the railings behind someone had put up a little lost baby’s mitten on one of the spikes. On closer inspection, the mitten turned out to be a ceramic sculpture.

At the back of the Thomas Coram’s statue was a brass plaque, but the light was too poor for me to make out what it said. We decided to make the Foundling Museum our first stop the following day. I’m glad we did.

It was easier to read the plaque in better light the following morning. And after visiting the museum and triple checking on the Internet, here’s what I learned about Thomas Coram.

Thomas Coram and the abandoned children of London

A native of Lyme Regis in Dorset, Thomas was sent to sea to work as a ship’s boy at the age 11. (This wasn’t unusual at the time.) He survived to become a seaman and eventually a shipwright. By the time he was 26 in 1698, he was living in Massachusetts in New England, still a colony of England at the time. He lived there for about 10 years, ultimately running his own shipyard.

By 1720, and now a merchant navy captain, he was living in London, making a living as a consultant on trade with the American colonies. (I think that’s what we’d call him today.) He was involved in trade and colonial relations with New England and Nova Scotia, and played a role in the establishment of the colony that later grew into the state of Georgia.

Living in Rotherhithe, then outside London south of the river, he often travelled into the City on business. On his way he passed through the poor quarters of Southwark. Here he was shocked by the squalor and especially by the number of children he saw living in extreme poverty. I’ve not been able to find exact numbers – they may not be available – but I’ve seen estimates of child mortality for the period that range from 20 dead by age 2 of every 100 born alive, up to 75 dead by age 5 for all births. (That last may include still-births.)

Walking the streets, Thomas Coram was shocked to see the “inhuman custom of exposing new born children to perish in the streets.” They were being abandoned by their destitute mothers, who turned to prostitution to supply their gin habit.

William Hogarth and Thomas Coram

Coram decided something had to be done, at least to save the children. He proposed setting up a hostel or hospital for foundlings or abandoned children. But how? And with what money? Coram was not a wealthy man and, he quickly discovered, his contact network did not reach to the highest levels of society where the real wealth of Britain was concentrated.

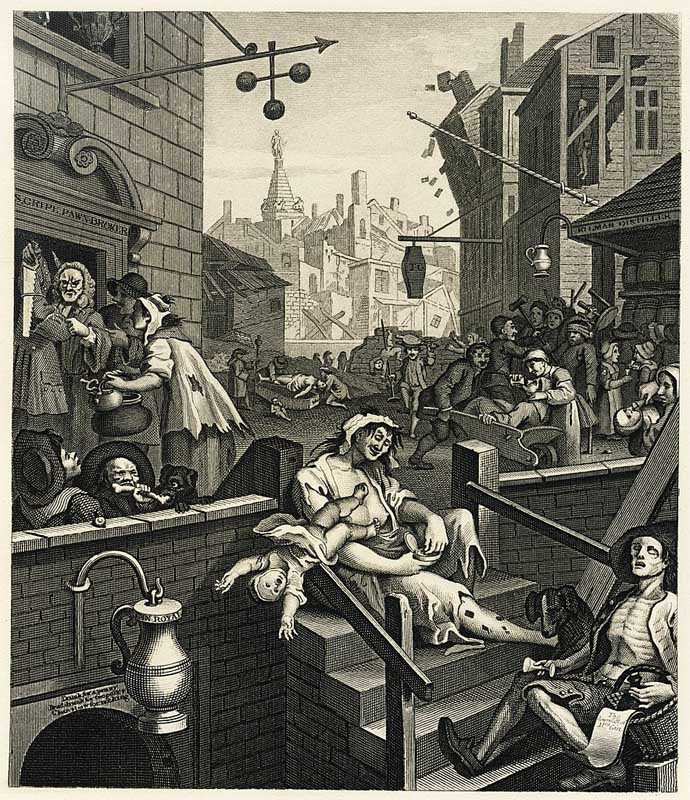

Fortunately he found a like-minded friend in the artist William Hogarth. Hogarth’s satirical engravings were both highly scandalous and immensely popular. They were morality stories drawn from real life. Printed in multiple copies for a few pence, they circulated like memes on social networks of today.

Gin Lane, for example, depicts the evils of cheap gin. A drunken mother drops her child over a balustrade while taking snuff from a box. An emaciated man looks like he’s just died, an empty glass in his hand, as a dog eyes him up as a meal.

Or The Harlot’s Progress which, in six frames, tells the sad story of Moll. A poor girl from the countryside, she came to London seeking work. She was finagled into prostitution and used and abused by wealthy men before dying, at 23, leaving her baby son an orphan.

Ladies of quality and distinction

Through Hogarth’s contacts, and the contacts of his artist friends, Coram was able to get introductions to some of the noblemen who sat for portraits. He had a petition to King George II prepared, calling for the establishment of the Foundling Hospital. But these noblemen turned out largely unwilling to sign. After nearly 10 years, Coram gave up on the men and started approaching their wives and daughters.

His first success was Charlotte, Duchess of Somerset. A month later he collected the signature of Ann, Duchess of Bolton, then Isabella, Duchess of Manchester. With 21 signatures of “ladies of quality and distinction” he presented his petition. It was rejected.

Coram started again, but now he had a growing band of noble supporters. The “ladies of quality” went to work on their husbands who one after another added their names to the petition. The second time he presented it, the petition was accepted. It had taken 17 years.

With the Royal stamp of approval, Coram could move on, in 1739, to organising his Hospital for the Maintenance and Education of Exposed and Deserted Young Children. First in rented accommodation, later in the purpose built Hospital that opened in 1745. The first 30 babies – 18 boys and 12 girls – were admitted in 1741.

Art, music and charity benefits

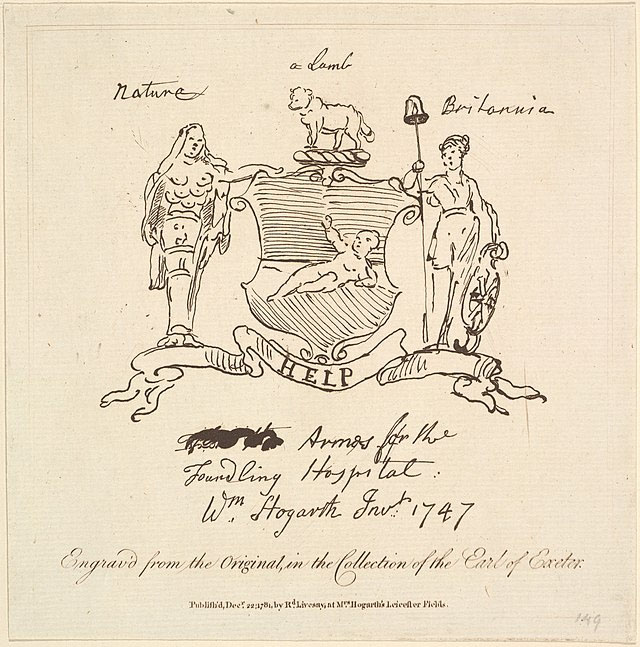

The question of how to pay for the hospital was solved by Hogarth who roped in his artistic friends. In particular, the court composer George Frederic Handel. Hogarth organised art exhibitions and Handel organised concerts and the proceeds went to support the Hospital. The patronage of the aristocracy that was a consequence of Coram’s efforts to get his Royal Charter continued. Supporting the hospital had become the fashionable thing to do. As a consequence, the Hospital, when built, included an art gallery (the first permanent public art gallery in London), and a hall for concerts as well as business meetings.

The original buildings are long gone. However the Foundling Museum’s Georgian-style building is built on the Hospital site. Inside, two rooms on the first floor reproduce the public rooms of the original. I understand the displays rotate, but when we were there the gallery had a number of portraits of women associated with the Hospital as benefactors.

Up on the top floor of the Museum is the Museum’s Handel archive. The composer left a collection of manuscript notations to the Hospital and this makes the Museum a magnet for Handel scholars and lovers of Handel’s music. It’s possible to sit in comfortable chairs, listening to Handel through headphones. Perhaps while you contemplate the startling collection of Handel memorabilia. On the ground floor are exhibition rooms for contemporary art, and the museum shop.

Tokens and children

All the above focuses on the Thomas Coram and the benefactors of the Foundling Hospital. But what of the children who the Hospital was set up to help?

First, they had to be healthy and under 12 months of age. they were admitted on the basis of a public lottery. Mothers who fit the Hospital’s criteria (which included being unmarried and destitute), pulled coloured balls from a bag. A white ball meant the baby was accepted pending a medical examination. A red ball meant the baby was put on a list to replace any of the white ball babies that turned out not to be healthy. A black ball meant the baby was rejected. (The term “blackballed” is said to come from the practice of voting using black or white balls to admit people to gentlemen’s clubs in the 1770s. Reading about the Foundling’s admission lottery from the 1740s has me wondering which process came first.)

Once they had been accepted, the babies were registered. This is where the most poignant collection of the Foundling Museum comes in. Each child was given a unique serial number and, to protect them from the “shame” of illegitimacy, a new name. However, their mothers were able to leave a unique identification token with the registration papers. The idea was, if the mother later wanted to reclaim her child, she could do so by describing the token as proof that the child really was hers.

Maids and bandsmen

These tokens were almost never used and remained in the Hospital archives, later to be inherited by the Museum. Among the tokens are nuts and coins, scraps of embossed metal, rings and bracelets, playing cards and scraps of lace. I’m not sure if there are any baby’s mittens, but Tracy Emin’s ceramic mitten on the railings by Coram’s statue outside the museum ensures there’s at least one.

There’s a fascinating, illustrated article here at MuseumCrush by Caro Howell, Director of the Foundling Museum, talking about them.

Once the babies had been accepted, they were sent to live with a wet nurse in the countryside away from London for a few years. At the age of 4 or 5, they moved to live communally at the Foundling Hospital where they lived as in a boarding school until they were 15 years old. After that they were apprenticed to a trade or to domestic service and moved out, although the Hospital continued to keep track of them until they were 21. Many of the girls went on to work as maidservants. As music was a significant part of their schooling, some of the boys became musicians in the army or navy.

The Foundling Hospital operated for a little over 200 years. Over that time it took in around 25,000 children. It was finally made redundant by changes in society and the law in the 1950s. The Hospital’s successor organisations are The Thomas Coram Foundation for Children (aka Coram) and the Foundling Museum itself.

Notes

I used a great number of internet sources putting this post together. Most of them are linked directly from the text, so I won’t repeat them here.

All the illustrations are my own photos taken during our visit to the museum on 16th March 2022. All except the following:

- The exterior photo of the Foundling Museum is by Alan Stanton, 2018 and is CC BY-SA 2.0 (via Wikimedia Commons).

- William Hogarth’s engravings Gin Lane and The Harlot’s Progress, the sketch of his arms for the Foundling Hospital, and the engraving from his painting Self Portrait with Pug are all long out of copyright. Again via Wikimedia Commons.

Great post, John. I particularly remember the tokens from my visit a few years ago.

Thanks for the comment Gail. Sorry the text was so long … I could have written half as much again!