Shut the doors and shut the windows! I know the sun’s shining and it’s perfect weather outside, but it’s birch pollen season too and the pollen count has been through the roof.

Hay fever never used to trouble me till I lived through a really serious birch pollen season in Norrland in 1993. That seemed to sensitise me, and now it plagues me every spring.

Hay fever never used to trouble me till I lived through a really serious birch pollen season in Norrland in 1993. That seemed to sensitise me, and now it plagues me every spring.

I know I shouldn’t complain. I’m sensitive to birch pollen and that’s about it. Once the birch pollen season is over, once we’ve had a little rain to wash the air, I’m back to normal. This annual two or three weeks of misery is my salutary reminder of the difficulties other people go through. My sister has been sensitive to all sorts of pollen since we were children and I’ve taught students who struggle through months of swollen eyes, runny noses and shortness of breath from early spring to the beginning of the autumn.

This year the pollen is more intense than usual, and it’s got me thinking about what this condition is called in Swedish and English and wondering when it was first identified. I mean, you wouldn’t expect that this was a new condition, would you? You’d expect that people have been having allergic reactions to pollen of one sort or another for centuries.

I think you’d be right, but it seems the term hay fever is only quite recent.

The standard Swedish word is hösnuva which makes me feel that Swedes don’t really take it very seriously. Snuva is what you call a runny nose, the sniffles. At least the English term involves fever which seems a lot more earnest.

A quick check on hösnuva in the Swedish Academy’s Online Etymological Dictionary shows that the word was first used in 1899; before that (from 1860) the condition was called höfeber … efter eng. “hayfever” as the dictionary says.

Good!

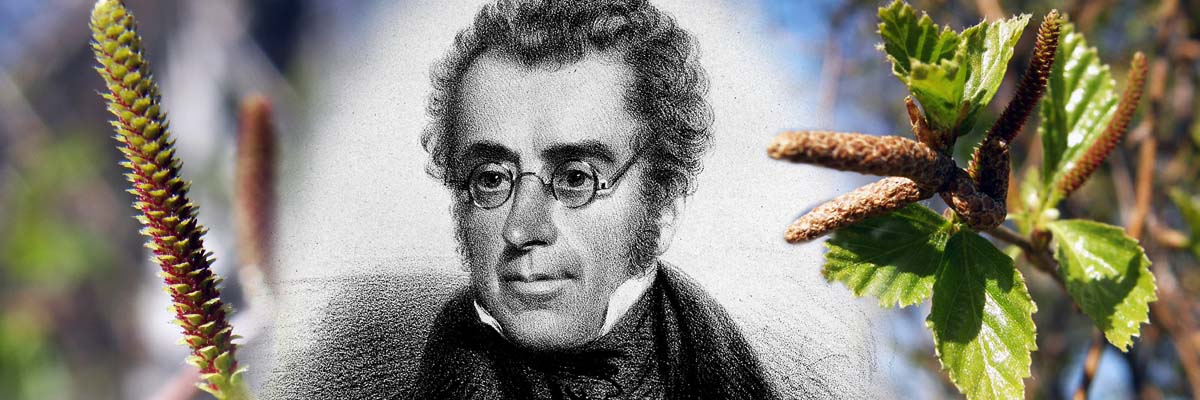

According to my edition of the Oxford English Dictionary, hay fever is first recorded in general use in English in 1829, but the term seems to have been coined ten years earlier by Dr. John Bostock.

He was himself a sufferer, was John Bostock, and as the disease hadn’t then been described, he set out to do so. His first paper was a study of a single patient (himself), but being a physician and a scientist he knew this wasn’t enough. He had to find other sufferers. This proved rather difficult. So difficult in fact, that Dr Bostock became convinced the condition was one that affected members “in the middle and upper classes of society”. In 1828 he wrote, “I have not heard of a single unequivocal case among the poor”.

I imagine Dr Bostock trying to identify fellow sufferers. As the disease hadn’t been described or identified, how would he have explained what he meant? He was trying to distinguish a specific condition so he’d probably have had to describe the symptoms he was after.

Bostock: Excuse me, my good fellow. Do you suffer from a seasonal springtime illness involving a sensation of heat and fullness in the eyes, an itching and smarting as of small points striking or darting into the ball, a copious discharge of a thick mucus fluid, a general fullness in the head, an irritation of the nose producing sneezing, which occurs in fits of extreme violence, a tightness of the chest and a difficulty of breathing, and a general irritation of the fauces and trachea? Possibly accompanied by a huskyness of the voice and an incapacity of speaking aloud for any time without inconvenience, a general indisposition, a degree of langour, an incapacity for muscular exertion, a loss of appetite, emaciation? Restless nights and profuse perspiration, your extremities however being generally cold, and an increase in your pulse from 80 to 100 or even 120 beats per second?

I wonder how many people of the day – especially among the poor – would have answered ‘yes’ to that.

The truth is probably that people who live in grinding poverty (and that describes by far the majority of the population of Britain in the 1820s) mostly have a very coarse interpretation of illness. Either you are really too ill to work – at death’s door – or you are not. If not, you get up in the morning, walk to the factory, the mine or out into the fields, work for 10, 12 or 14 hours, walk home, eat what food is available and then sleep until it’s time to start over again.

It’s only folk in “the middle and upper classes of society” who have the leisure to allow themselves feel ill with minor complaints.

And yet, that’s not true either. Even if you’re poor you might well complain of ailments that make your life temporarily even harder.

Modern “hay fever” aside, there is a long tradition of not feeling on top of things in the spring. There’s an equally long tradition of exactly the opposite. There’s another term for this: Spring fever.

For some people spring fever is the term of preference for the obsession with cleaning that seems to seize people at this time of the year. For others it clearly means “an increasing energy, vitality and sexual appetite” or to quote another website “spring fever is when you get hot and horny”. No, I’m not going to link to that. 🙂

Instead I’ll give you this – a definition from the Urban Dictionary. Spring fever is … “Excessive horniness eclipsed by post nasal drip.”

Another definition suggests spring fever is actually the same thing that Swedes mean by vårtrötthet and Germans by Frühjahrsmüdigkeit; the tiredness you feel in the spring as the days grow longer. This in turn is variously interpreted either as an aspect of Seasonal Affective Disorder or as a physical weakness. (And I see from the current definition in Wikipedia that the physical weakness can also include “aching in the joints”.)

The Wiktionary identifies spring fever as a contranym, a word which functions as its own antonym “capable of meaning either invigorating or listlessness”.

A little bit more of a search on the Internet turns up another term, this one from the Old English: lenctenadle. The first part of the word comes from lencten (preserved in Lent) which was the Anglo-Saxon word for spring, the second part of the word, -adle, meant disease or sickness.

Hay fever, spring fever, Lenten fever… are these perhaps one and the same thing? I’d like to believe it, but I’m not sure. The Anglo-Saxon dictionary I’m using glosses lenctenadle as either spring fever or … tertiary ague. Tertiary ague is a form of malaria! You get the shakes (the ague) every third day.

Hay fever, spring fever, Lenten fever… are these perhaps one and the same thing? I’d like to believe it, but I’m not sure. The Anglo-Saxon dictionary I’m using glosses lenctenadle as either spring fever or … tertiary ague. Tertiary ague is a form of malaria! You get the shakes (the ague) every third day.

On the one hand it’s malaria. (This is certainly something a damn sight more serious than snuva-snuffles!) On the other hand, it’s feeling a bit low after a dark northern winter. On a third hand (look, this is a metaphor, ok?) On a third hand it’s the desire to clean (or nest), and on a fourth hand it’s the urge to procreate.

So where does all this take us?

I think spring is at one and the same time the allergy season and the season of potency, and I think it’s always been like that. The evidence is preserved in the language, though perhaps it was never before so prominent.

Nowadays we have more leisure to suffer-enjoy all the sides of the season – and to investigate it, whether scientifically or bloggologically.

(I’m going to have to work on my blog entry endings. That one’s really lame!)

This blog entry is a bit of a cheat. A lot of this article has already appeared – in a slightly different form – on one of my other blogs, in another age. Why repeat myself? Well, first of all hay fever is topical. I spent the last week suffering from the highest birch pollen counts for 20 years. And because of the hay fever (and one or two other trifling matters such as a bad head cold and my tax declaration) I really haven’t had time to prep an all-new blog entry for this week. The illustration of Dr John Bostock comes from Wikipedia.

This article was (re)written for the #Blogg52 challenge. I originally published it on the separate At the Quill website. I revised it for spelling and punctuation, carried out some SEO fine-tuning, and added a featured image before transferring it here on 2 April 2017.

I have sometimes thought about how allergy (of which hayfever is one kind). When I was a child there did not seem to be so much allergies. I wonder if that was true of if they were just not heard of as often as today. One or to of the other children had astma, that was it. Nobody talked about other allergies. I sometimes wonder why?

ps: I like on the third hand!

Glad you liked the third hand! 🙂

I agree, allergies didn’t seem so common when we were young… but they were certainly present in my family because my sister used to have terrible reactions, especially to grass. She would turn red, her face would swell and she would gasp for air (and panic). The first time I remember she was 3 or 4 (I was 6). The doctors tell me I’m probably genetically predisposed and became sensitised in ’93 just because there was so much pollen in the air.

I edited the English in a doctoral thesis, some while back now, for a medical doctor who had done comparative research into allergies in Sweden, Poland and the Baltic States. As I recall, one of his tentative conclusions was that modern cleanliness indoors may be a contributing factor. And who knows, the chemicals we modern humans have introduced into our food, water and air may have something to do with it too.

But it could also be a social phenomenon. That we in our society are more willing to recognise allergies now than we used too be, and more prepared to talk about our allergic reactions. Earlier, we were all supposed to keep a stiff upper lip (or whatever the Swedish equivalent is) and only the people like my poor sister who were completely prostrated by their allergies got any sympathy.

I’m a self-proclaimed sucker for etymology, so this article of yours was a nice treat. Thanks!

Thanks! Glad you liked it. A fellow word nut, eh? I love etymology (and folk etymology – I think there’s a bit of both in the article 🙂 ) – there may be more to come…