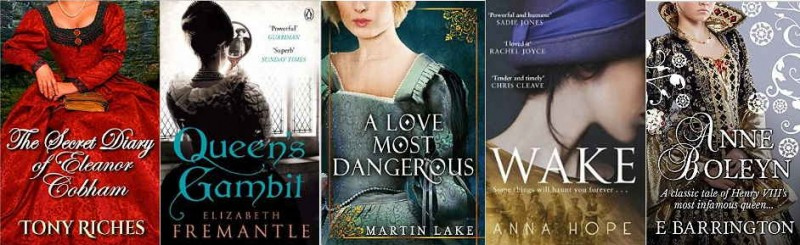

There’s a puzzling visual cliché on the cover of a lot of books of historical fiction where women are protagonists.

The headless woman

In Writing Historical Fiction, (reviewed in my last article), Celia Brayfield writes about what she calls “the headless woman” phenomenon. It’s not just that women’s heads are lopped off, they can also be hidden, turned away or blacked out. It’s difficult to know what goes through the heads of publisher’s art directors when they make this choice. Brayfield uses this as one illustration of “the tensions that an author has to resolve when creating a female protagonist in a historical novel”. To be honest, I’m not entirely sure what she means. Not that I misunderstand her words, but I don’t understand how the headless women illustrate what she wants to say.

My gut interpretation is that publishers’ art directors assume that these books will most appeal to women. They assume women read historical fiction to vicariously experience life in another time, and that if the face of the heroine is unidentifiable it makes it easier for the reader to identify herself as the heroine. I’m not saying I believe this to be the truth myself. It’s the only interpretation I can find that seems to make sense. Because it is absolutely true. An astonishing number of novels of historical fiction with female protagonists are illustrated on their front covers by women whose faces are invisible.

More or less Tudor

The five book covers I’m using to illustrate this article, for example. I took them from first few pages of Amazon UK’s current historical fiction lists. I picked the ones that seemed more or less “Tudor” but I could have included others from earlier and later historical epochs. Not all books with female protagonists set in historical contexts are illustrated like this. Also there are a few (a very few) books where a male protagonist is similarly portrayed. But the broad tendency is very obvious.

What this cliché illustrates – unintentionally – is the way women’s lives and experiences have for centuries been hidden in history books. (I think this may be what Celia Brayfield is getting at.)

His distorted history

At the core of the novel I am myself attempting to write is Elin’s true story. When I came across it, I was astounded I had never heard of it before. A young woman travels from Sweden to England in the 1560s. She becomes a Lady in Waiting at the court of Queen Elizabeth I. She marries the Queen’s step-uncle and ends up as the senior English female aristocrat and mourner at Elizabeth’s funeral in 1603. When I looked in the sources, I found her. But I’d studied Tudor history at school and at university so why I was learning about Elin only now? More than anything else, discovering Elin’s story made real for me the criticisms feminist historians have been making for years about the way in which history has been distorted by male historians.

It also illustrated what I had been teaching in my periods as a history teacher: that the history we know is the story that was told to us. Everybody – even the most well-intentioned and scrupulously balanced historian – is biased in some degree. They may try, they should try, but they cannot help allowing their bias to influence the story they tell. Everyone needs to be wary of bias – and of prejudice – their own and others’. There is so much more in the source material. This means every generation comes to the same material with new questions, new perspectives and new interpretations. And may come away with new stories.

Be wary of bias

And we can – we should apply this thinking to stories in the news and the tales we’re told by people around us as much as to stories from history.

Not sure how much of that came across – here, now, or to my students back then. But I live in hope.

This article was written for the #Blogg52 challenge.

I originally published this article on the separate At the Quill website. I revised it for spelling and punctuation, carried out some SEO fine-tuning, and added a featured image before transferring it here on 10 April 2017.

Amazing! Especially as some covers above are from books about famous women. I guess it is known what Anne Boleyn looked like.

And I have never before noticed, I will look more at the bookcovers in the future.

It really is amazing, isn’t it Eva? Celia Brayfield illustrates her comments with books by well-known authors of historical fiction – incuding Phillipa Gregory’s The Other Boleyn Girl. I doubt very much the illustrations are the authors’ choices, they must be the pubishers’ responsibility. Another argument for self-publication perhaps. Brayfield even shows history books can get caught in the trap. She includes the cover of She Wolves: The Women Who Ruled Englnad Before Elizabeth, an academic study by Dr Helen Castor of Cambridge University. The cover of her book shows a portrait of Elizabeth I, cut off just above the nose!

What’s more amazing still is that, like you, I hadn’t noticed it before – but once it was pointed out I couldn’t not see it!

Vilken intressant iakttagelse.

Tack Pernilla. Fascinerande eller hur?