It seems to be very human trait to give names to certain objects. Sometimes the names are very personal, individual. In my family, we once had a car called Alf (because those were the letters on the number plate). Houses often have names, ships too, of course, painted proudly on their sides. And we also name weapons.

Lately, sadly, we have been learning a lot of the names of certain weapons. This got me thinking about one specific name, which I want to argue is the single most successful given name for a weapon in human history. At least in the English language. But I’ll come on to that later.

For the moment, let me share a few observations. It seems to me that weapons get named in three or four different ways.

Matter-of-fact and simple identification

First there are the names assigned in factories where the weapons are constructed. I’m thinking of names like T-72, MiG-29, AK-74. Those are all weapons in use on one side or the other in Putin’s war in Ukraine. But I could add, for example, the Colt 45, the Bofors 40m, or the B-52. These names incorporate either the designation of the weapon (T = tank) or the initials of the engineer (AK = Avtomat Kalashnikov – literally Kalashnikov’s automatic rifle), or the name of the company or factory (MiG = Mikoyan and Gurevich). In the Western world, Colt and Bofors are company factories, B-52 stands both for bomber and Boeing.

Considering how very matter-of-fact and boring this nomenclature is, it’s interesting how recognisable some of these terms are. I’m going to go out on a limb here, but I think the two winners in terms of general recognition are Colt and Kalashnikov. I don’t suppose either Samuel Colt or Mikhail Kalashnikov ever anticipated their names and their guns would achieve such worldwide fame, though I imagine they were both gratified to see it happen. Colt, as a hard-nosed capitalist, recognising it would only enhance sales of his guns; Kalashnikov, as a good communist, seeing his guns put to revolutionary use.

Kalashnikov’s AK-47 even made it onto the flags or coats of arms of Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Burkina Faso (briefly) and East Timor. Not something that ever happened to Colt’s weapons as far as I know. Though one of Colt’s guns – not the 45 but the 357 Magnum – with its barrel twisted into a knot, stands as a peace sculpture outside the UN headquarters in New York.

Commercial and Propaganda names

Beyond this highly practical naming, are the various colourful, dynamic or cynical names which some weapons of war are given. I get the feeling these are devised by committees of advertising executives and propagandists. (Possibly moonlighting from IKEA.) The names are intended to bolster the morale of the troops using them and undermine the morale of the enemy. Also to encourage third-party countries to buy them for their own armed services.

Some examples in the present war are Kalibr and Iskander (these are two types of Russian missile in use in Ukraine). Kalibr (calibre) emphasises the practical and the reliable, it might almost have been named by an engineer. But Iskander (Alexander) is surely intended to call to mind the military achievements of Alexander the Great. Or of Tsar Alexander I, triumphant against Napoleon.

For their part the Ukrainians are deploying American-made Stinger and Javelin anti-aircraft systems. It’s easy to see that these were named with the intention of saying something about their mode of use (they are portable), as well as their effect.

An anti-tank weapon, apparently in use on both sides, is the AT4, a Swedish made “single-shot disposable”. Wikipedia tells me that the name AT4 is a homophone, playing on the weapon’s 84 mm calibre. “The name was created for export purposes.”

Bad weather and garden flowers

Something we have seen a lot of is Russia’s indiscriminate shelling of urban areas. These terror attacks seem intended to kill or maim civilians and destroy property and infrastructure. The weapons systems Russia is using include the Grad, Uragan and Smerch (Hail, Hurricane, Whirlwind) rocket artillery. They’re also using the self-propelled artillery systems Gvozdika, Akatsiya and Pion (Carnation, Acacia, Peony). These appear to be official names, so I wonder who named them and why. A touch of Newspeak?

For their part Ukraine is pushing back with successful use of Turkish built drones called Bayraktar (flag bearer.) The Baykar Bayraktar TB2 (where Baykar is the manufacturer’s name) is a MALE – medium-altitude long-endurance unmanned combat aerial vehicle. (Thank you again, Wikipedia.) I have a feeling that “MALE” will cause women readers – and some others – to shake their heads and mutter, Well, of course.

Tanks and ships

I’ve used one extraordinarily successful name for a weapon several times so far. It’s not the most successful, but probably it holds second place.

The name tank was first used during the First World War when the British Navy constructed the first “land ships” and transported them to the Western Front in crates marked “water tank”. The name was adopted by the soldiery and stuck. So much so that it became the generic English name for this type of weapon. As you read earlier, it was even adopted into other languages. Russian anyway.

(There is a whole literature devoted to the origin of the tank, including its etymology. The above paragraph barely scratches the surface.)

While weapons systems get official names, individual weapons rarely do. Except when they are big and significant. Warships for example.

The most significant named vessel of the Russian Black Sea fleet at the start of the war was the Slava class guided missile cruiser Moskva. It was Russia’s flagship, named after the Russian capital city, carrying a crew of 510. Reputedly, also, a fragment of the “true cross”. Lots of metaphorical significance packed into a single weapon.

The Ukrainians sank it with a combination of Bayrakter drones and one or two of their home produced Neptune anti-ship missile.

Actually, Russia has not admitted losing the Moskva in an attack. They have admitted that the ship blew up and sank. The loss of life from among the crew is unknown.

Designations

Gathering the information to write this post, I came across another category of weapons naming I hadn’t thought of from the beginning. While one side may name their weapons for propaganda purposes, or happily use the factory identifications, the other side also has an interest in identifying the weapons, and perhaps not by adopting the nomenclature of the enemy. For example, Wikipedia tells me that Russia’s Oniks supersonic anti-ship cruise missile has the NATO codename Strobile.

I had to look that up. It’s a botanical term for the overlapping scales on, for example, a pine cone.

To an outsider this plethora of names can get quite confusing. I guess (I hope) the soldiers most immediately concerned know what they’re talking about.

Nicknames

And so we come to the last category, which I was going to call “soldiers’ nicknames”, until I realised that was ambiguous. I mean the names that weapons are given by the soldiers who use them. I’m thinking here of the bomb used in Vietnam that the soldiers called the Daisy Cutter. It was used to flatten a section of forest to create a helicopter landing zone.

Or how about the Tommy gun? The soldiers’ abbreviation of the Thompson machine gun that came to be identified with gangland racketeers during the American Prohibition. Or the Brown Bess – the muzzle-loaded musket that was standard issue for the British Army between the 1720s and 1850s.

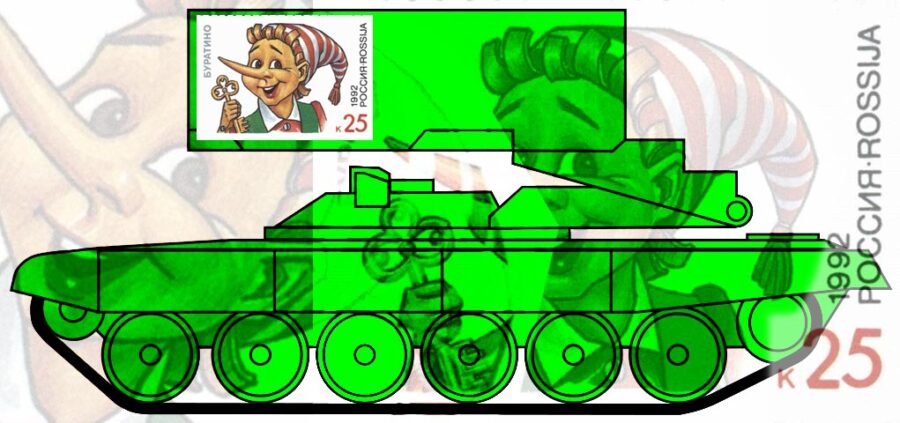

In respect of the current war, the Russian’s TOS-1 multiple rocket launcher is nicknamed Buratino. Buratino is a long-nosed Pinocchio character from a children’s story by Tolstoy. Apparently Russian soldiers think that this weapon has a long nose.

On the Ukraine side, some soldiers are equipped with the Swedish (Bofors) made Carl-Gustaf recoilless rifle. I don’t know what Ukrainian soldiers call these guns, but apparently Australian servicemen, who also use them, call them Charlie Guts-ache.

(Be assured, I’m not contractually obliged to include Swedish-slanted references in my blog posts. It’s just that sometimes I feel like doing so. You’re welcome.)

The original gun

All this is bringing me to my punch line. There is one generic name that I think can be reasonably called the single most successful weapons name in history. Certainly in the English language. It is, of course, gun. Most of the rest of the world uses some variant of pistol, which has its own interesting history, but I’m going with gun. Not least because a gun has a much wider sense than pistol which can only be a handheld weapon. Guns can be big guns too.

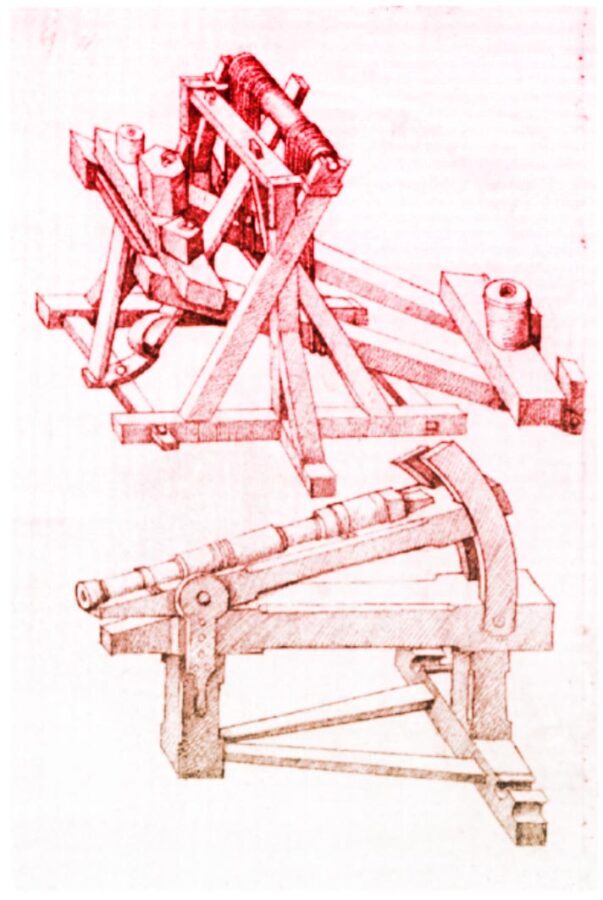

The original gun was pretty big. A siege weapon.

If you know your Lord of the Rings, you will recognise that siege weapons can have names. In the The Return of the King there is a massive battering ram, constructed in Mordor:

… a huge ram, great as a forest-tree a hundred feet in length, swinging on mighty chains. Long had it been forging in the dark smithies of Mordor, and its hideous head, founded of black steel, was shaped in the likeness of a ravening wolf … Grond they named it …

As with modern battleships, when you have a weapon that is is practically unique and vastly expensive, there’s a tendency to want to name it uniquely. Windsor Castle in the 1330s housed a large ballista, a kind of giant crossbow. In the castle’s inventory of weapons it is named Domina Gunilda, the Lady Gunilda.

The Lady Gunilda was not a firearm, but it seems she passed her name on to the earliest cannons used by the English. They were called gonnilde, after which came gonnes, gunnes and guns.

Name your weapons

So that’s how guns got their name, and a lot else about the naming of weapons. I feel a little grubby for using the war in Ukraine as a hook for a blog post. Still, I hope you found it interesting.

Notes

The original elements of the illustrations are all sourced from Wikimedia Commons. The only uncollaged image is the last. This comes from the Mittelalterliche Hausbuch von Schloss Wolfegg. The medieval house book of Schloss Wolfegg is a handwritten compendium on various topics of practical knowledge useful for aristocrats and family members, written and illustrated by several artists and scribes around 1480, probably in the Middle Rhine region. (Translation via Google Translate from the German language Wikipedia.)