Fantastic!

I’m still feeling buoyed up by the experience of seeing Phædre yesterday evening. What a fantastic performance! And what a fantastic use of technology! Here, in Gothenburg, in Sweden, to be able to see a performance direct from a stage of the National Theatre in London. A no-holds-barred performance, not dumbed down for a provincial public, or subtitled, or with actors performing at anything less than their professional peak. The images were almost always crisp and clear and the cutting from camera angle to camera angle was choreographed almost to perfection. In the auditorium of the cinema we had a better view of the actors’ expressions than I’d guess many people sitting at the back of the theatre in London did. The sound quality was also generally very good, and with surround-sound we could hear and share the reactions of the live audience.

People who have seen the operas that have been broadcast in this way may not have been so bowled over by the Phædre experience, but this was my first taste of modern direct-feed technology. I found it captivating.

Gripping

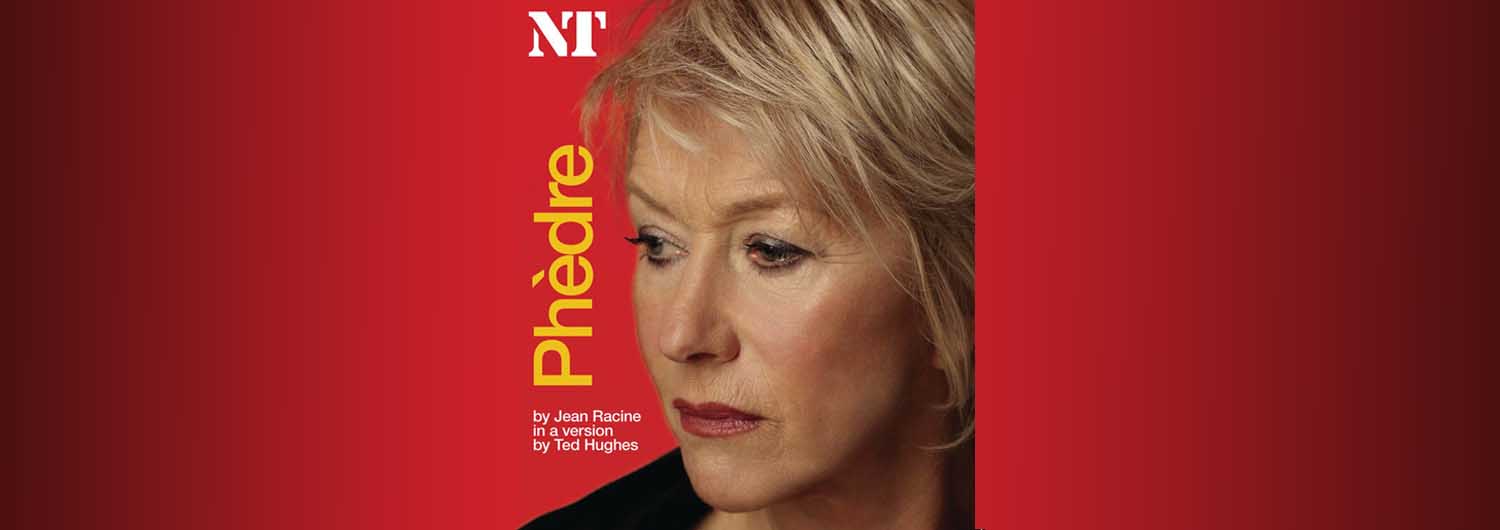

Of course, it helped that the play was so gripping, the language so powerful and the actors, all of them, so brilliant and working so well together. I came, I admit, more than half because of Helen Mirren, and she was magnificent as Phaedre. The older woman consumed by incestuous desire for her husband’s son, confused by her feelings, desperate to resist them but unable to do so, torn and poisoned by them, sometimes the perpetrator sometimes the victim. Mirren gave the character life and depth.

But this was an ensemble piece. If any one of the principals had been performing under par, it would have drawn down the quality of the whole.

Hippolytus

Dominic Cooper as Hippolytus, the young prince of fast principles who is the object of Phaedre’s desire and the focus of her jealousy, was a revelation. (In the Swedish language flier ticket buyers received here he is “known from Mamma Mia! as Meryl Streep’s son-in-law-to-be”. I didn’t find that helpful.)

Hippolytus represents youth, nobility, restraint and moral probity. The son of the hero Theseus and his first, Amazon wife Hippolyta, but not himself the stuff of legend. Set aside by Phaedre and displaced from succession by her children, Hippolytus is yet not resentful. He honours his father, even though disapproving of his reputation as a womaniser. It can’t be an easy task to play this role without making the character seem either anonymous or a prig, but Cooper manages to make Hippolytus both believable and likeable. Essential for the play to work, of course, since the tragedy turns on Hippolytus’s reaction to Phaedre’s advances and then to her false accusations of rape, and to his father’s rejection and curses that ultimately lead to his death.

Cooper’s efforts to make Hippolytus likeable are helped, of course, by his love for Aricia and the love she holds for him. Aricia is the last surviving heir of an Athenian family that Theseus has all but wiped out. Although she is innocent of any blame, and so cannot be killed, Theseus still fears her. He has left Hippolytus instructions to guard her well.

Aricia

Aricia, played beautifully by Ruth Negga, is a young woman who, in the course of the play, is taken from a condition of fear and uncertainty through the giddy experience of freedom and sudden love to the edge of despair.

Hippolytus, keeping his word to Theseus, waits until receiving what he believes is reliable information that his father has died before revealing his love, releasing Aricia and promising to help her take what he believes is her rightful place as Queen of Athens. A modern audience may well find itself wondering why he waits; if he truly believes his father is wrong to hold Aricia, if he truly loves her. Again, this could easily come across as weakness, but Cooper’s performance, helped by Negga’s, makes all this reflect positively rather than negatively on Hippolytus’s character.

Oenone and Theramenes

Margaret Tyzack and John Shrapnel as Oenone and Theramenes, respectively Phaedre’s and Hippolytus’s companions, are also strong in their supporting roles. Both had their outstanding moments. Shrapnel’s Theramenes has his most gripping scene at the end when he describes Hippolytus’s death struggle with the earthquake-tsunami-monster from the deep.

Oenone has more stage time and is more intrinsic to the story, although she is the first character to die. Oenone only wants the best for her girl and cannot see that the actions she encourages Phaedre to take lead to disaster. She has some good scenes, but her final appearance was gripping, when she realises she has lost Phaedre’s affection and, perhaps, comes to an understanding of the tragedy she has partly caused.

Oenone’s departure from the stage is the only criticism I have of the editing choices made by the technicians. At the end of her scene she crossed front stage right and presumably leapt to her death from the balustrades. But the camera allowed her to pass out of shot and we neither saw her jump nor leave the stage. I thought this was a bit clumsy.

Finally there is Stanley Townsend’s Theseus, who returns triumphant from the shores of death to precipitate the tragedy.

Phaedre and Theseus

Neither Phaedre nor Theseus can see Hippolytus’s true worth. Phaedre falsely accuses Hippolytus of rape in the belief that she is pre-empting his own accusations. Theseus, who has seduced so many women in his time, and whose most recent dice with Hades started out as an escapade to help an old friend cuckold another ruler, chooses to believe Phaedre’s falsehoods rather than accept his own son’s assurances. Like any modern cynic, he finds it easier to believe in corruption than in innocence. And so the stage is set for the final tragic outcome.

As I say the story, the language and the acting combined made this a play that would have been gripping to see in any theatre. In a way, I wasn’t expecting anything less. But I did enter the cinema with some doubts.

Filmed play?

What I was expecting was a filmed play. I was expecting it to be rather static, to be viewed from just a few camera angles front of stage, for the actors to be in the middle distance, for the sound to be muffled at times and for the microphones to pick up and amplify inadvertent sounds (breathing, rustling of clothes, bangs, clicks or footsteps). My expectations went mostly unfulfilled.

Of course, Greek tragedy is rather static, even transmitted via Jean Racine and Ted Hughes. It is difficult to ignore for example the unities of time and place which are so alien to modern drama. Still, because of the camera angles, the close-ups and the way the cameras could follow the actors about, I did not feel the play was at all as static as I had feared. The sound quality was generally very good. (Though a bit over-loud in places and especially during the first 20 minutes or so.) There were changes in sound quality at times, but nothing like as significant as in many filmed plays I’ve seen. I don’t think there were any words I couldn’t hear, and yet the performance was very natural without anyone over enunciating.

Above all the actors seemed comfortable, not as though they were playing for the cameras.

Bio Roy

The cinema Roy on the Avenue, Gothenburg’s main street, started to show direct-feed events about a year ago after closing as a regular cinema. It is part of a chain of digital cinemas across Sweden run by Folkets Hus och Parker (the People’s Houses and Parks movement). They offer alternative venues to the commercial cinema. Up to now, their stock shows seem to have been operas. At least those are the shows I’ve mostly been aware of. Opera has a limited, but often a more dedicated audience and music is a more universal language, so I can understand how it might have more appeal in a country where English is not the mother tongue.

Of course, many Swedes understand English to a high level, but I did have my doubts about this. A dense, complex and relentless stream of language without subtitles. How would the audience react? The first ten minutes or so were difficult for some at least. The woman in the seat in front of me was paging through screens on her mobile phone until I tapped her on the shoulder. (And I’m not talking about teenagers here. The average age of the audience at Roy looked to be a good generation older than the average age of the audience in London.) But this is where the quality of the acting made itself felt. Even if people did not understand every word or even every sentence, the power of the acting carried the message across. After about ten minutes the audience was captivated.

Applause

In the end, as the audience in London applauded, so did we. And at least some of us kept on applauding as each of the actors took their bow. From the response I read on Twitter after the play, mine was not the only cinema audience that reacted with applause. I wish the communication had been two-way so the cast in London could have seen and heard the impact they had around the world.

There are three more direct-feed plays scheduled from the National over the coming year. After this experience, I will do my best to get to see all of them. And spread the word. Bio Roy was not full by any means and I want this exercise to be so successful that more plays will be offered in the future. That more theatre companies will be encouraged to invest in the technology to broaden their audience in this way.

Further notes

The above is a review of the British National Theatre’s live production of Phaedre on 25th June 2009. Actually the transcript of a podcast-style review. Originally I had the post include a link to the recording, saved on-line. I say it was “podcast-like” because I think a podcast needs to be in a series, not a one-off. The on-line server no longer holds the recording which seems to have been erased. But anyway it called for you to have Flash software installed on your device to be able to stream it. Who has Flash anymore? (Who remembers there was ever a software called Flash?)

But I was pleased with the text and I think the article is interesting. On the one hand as an example of what I was expecting before going to see the piece. On the other for the technical things I single out for praise. Nowadays the NT streams are subtitled, which in my view is distracting.

I saw all four plays in the first season. I shared further comments on the technology in similar reviews. If you’re interested, follow these links:

All’s Well That Ends Well on 1st October 2009

Nation on 30th January 2010 (Apparently I didn’t write a review, though I definitely saw the play.)

The Habit of Art on 22nd April 2010

Wikipedia tells me there was a fifth play in the first season. It was London Assurance, streamed on 28th June 2010. I didn’t see it though. On the other hand I did see and review The Cherry Orchard with Zoë Wanamaker on 30th June 2011.)

[18th July 2019]