It’s ten years since the death of Russell Hoban. To commemorate this, Penguin has republished eight of his novels for adults, something I was alerted to by The Guardian’s Book of the Day column in May. Eight? I did a quick count of the ones I remembered reading (Riddly, Turtle, Lion …) and came up three short. Only three? And only eight? Wikipedia’s page for the author lists no less than 16 novels for adults. Not to mention (by my count) 40 titles for children and the odd film script and opera libretto.

Tuning in

I first came across Russell Hoban’s writing in an early issue of Granta magazine. It was an essay about memory and music – specifically Indian music – and the idea of time. I don’t recall very much, but it made an impression. He described his writing space, a large table in the living room of his flat in Fulham. There he sat, writing and listening to a broadcast, from All India Radio, of a raga in the night.

This was long before the Internet and streaming services. He was tuning in with a radio receiver, perhaps on shortwave. At the time I read his essay, I was myself sitting at my kitchen table in Bulgaria or Finland, the winter night drawing in as I tuned my shortwave radio to the BBC World Service. I felt a strong fellow feeling. Also, Fulham! From his window he saw passing the red and green lights of District Line trains in the dark. I was homesick – and I’d never even lived in Fulham.

On-line, excepting the Russell Hoban fans, most people who know his writing fall into two groups. The parents who know his children’s books and the adult readers who praise Riddly Walker. On the Books by Russell Hoban page of GoodReads, sorted by popularity, books in the Frances the Badger series occupy six of the top ten spots. Riddly Walker is placed fourth. Not being a parent I have never read any of Hoban’s children’s stories, but I think I may have heard The Mouse and His Child read on the BBC’s Jackanory children’s programme sometime in the 1970s.

Riddly Walker and Turtle Diary

There’s an interesting illustration of my sweeping statement in that last paragraph in a review of Turtle Diary from The Atlantic magazine August 1976. (A PDF on the russellhoban.org website.) The reviewer devotes a paragraph of the essay to Turtle Diary, and then the remaining five to the Frances books, all published at least five years before.

Riddly Walker was my entry port to the imagination and storytelling of Russell Hoban. In a post-apocalyptic Inland (England), Riddly Walker is the protagonist and our guide. It’s not an easy read, being couched in a corrupt and twisted language of the far future, but Riddly’s pleasure in using it, and the world he describes, are great magnets. I guess some people would toss the book aside because of the language, but it was an attraction for me – and for many others.

More accessible by far is Turtle Diary published five years before Riddly. Turtle Diary is set in contemporary London and follows two lonely and slightly embittered middle-aged people, William and Neaera. By chance, their paths cross at London Zoo and they discover a mutual desire to kidnap the giant sea turtles, confined in a tank too small for them, and release them into the sea. It’s a wonderful story about escaping loneliness and overcoming embitterment, and gracefully sidesteps the romantic relationship that seems set up between the two protagonists. A film was made of it in 1985 with Glenda Jackson and Ben Kingsley in the lead roles.

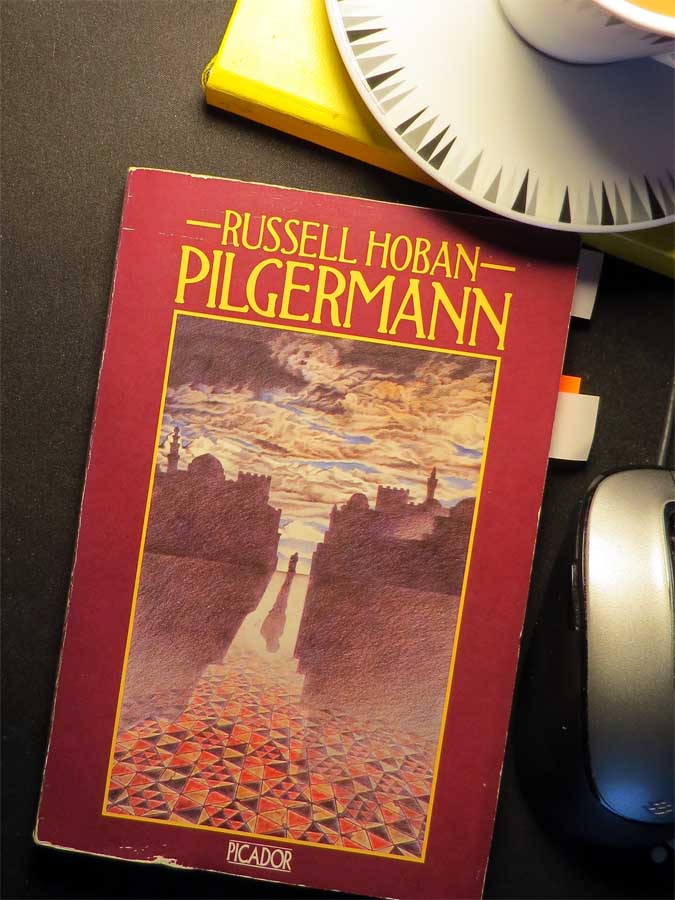

Pilgermann

Both Riddly Walker and Turtle Diary are among the eight newly republished as Penguin Modern Classics, and I thought I’d like to re-read either of them. But when I looked on my bookshelves, all I could find was Pilgermann. A lot of my books are packed away in storage so I’m pretty sure I still have the others, but I don’t know why the only Hoban I can put my hand on is one I was never keen on when I first read it. Something about the Crusades, was it?

Oh yes, and so much more! Have I matured as a reader since the first time I read Pilgermann? I might have. Or maybe I never finished it back then in the heady days of my youth. (Pilgermann came out in 1983 and I read it a couple of years later.) When I read it now there were chapters that I’d swear were completely new to me. But then I’d come across an image, or a snatch of dialogue, and I sensed an echo from when I must have read it, thirty plus years ago. Déjà vu.

In one sense the novel is historical fiction. Pilgermann is a Jew in 11th century Germany. He is castrated in an act of anti-Semitic violence, part of the wave of such violence sweeping Christian Europe at the time. (To be fair, he has just seduced the Christian wife of the man who orchestrates his castration.) Disguised as a Christian pilgrim, he flees Germany, joining the movement of people towards Jerusalem that accompanies the First Crusade.

Waves and particles

In another sense, the novel is wholly other than historical. The narrator begins:

Pilgermann here. I call myself Pilgermann, it’s a convenience. What my name was when I was walking around in the shape of a man I don’t know, I simply can’t remember. What I am now is waves and particles, I don’t need to walk around. I just go. …

page 11

I don’t know what I am now. A whispering out of the dust. Dried blood on a sword and the sword has crumbled into rust and the wind has blown the rust away, but still I am, still I am of this world, still I have something to say, how could it be otherwise, nothing comes to an end, the action never stops, it only changes, the ringing of the steel is sung in the silence of the stone.

… I speak from between the pieces; I speak from where Abram heard the voice of God…

From which the reader understands that the spirit that was Pilgermann is still to be heard. That his waves and particles can be tuned in, like tuning in a shortwave radio receiver. And also that this book is not just a story about a reluctant pilgrim on the First Crusade, but is also about eternal things. About the passage of time, about belief and theology. And about what, if not eternal, does seems to be a never-ending conflict between proponents of the monotheist religions, Islam, Christianity, Judaism.

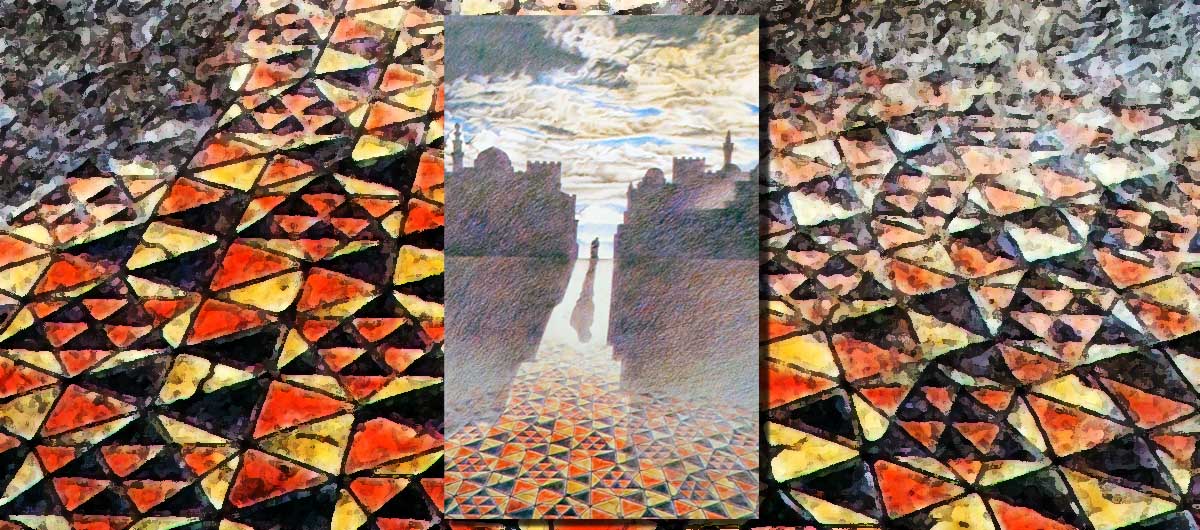

It also has detailed instructions (with sketches) on how to create an infinite pattern from three differently coloured triangular tiles that at some point will begin to move “intransitively”. (Page 118 and forwards.)

The Medusa Frequency

Here are a couple more quotes:

One wakes up in the morning and puts on oneself. Everyone has experienced this: the self must be put on before any garment, and there is inevitably a pause as it were a caesura in the going forward of things before the self is put on.

page 124

Such an interesting moment, that moment before someone who is not a Jew asks you if you are a Jew!

page 139

It took me 13 days to read Pilgermann and now I want to read more. That Guardian article I mentioned above says Hoban himself claimed The Medusa Frequency held the key to his writing, so that’s now on my “to be read” list. Once British bookshops have sorted out how they can sell books to Europe through the trade barriers Brexit has imposed. (I don’t buy from Amazon unless I can’t help doing so. And you shouldn’t either! From my soapbox.)

I started out intending to write you a reading diary entry about several books recently finished, but Russell Hoban and Pilgermann demanded more space. I hope you found this post at least half as interesting as I found it, myself, to write. Maybe I’ll get around to reviewing the other titles next week.

I used to love Russell Hoban’s books! I guess I still do, though it must be 35-40 years since I read them (Riddley, Turtles, Kleinzeit and The Lion of Joachin-Boaz…). They await re-reading in my bookshelf.

Just those titles await re-reading somewhere in my storage space! I’ll unearth them eventually – I hope.

🙂