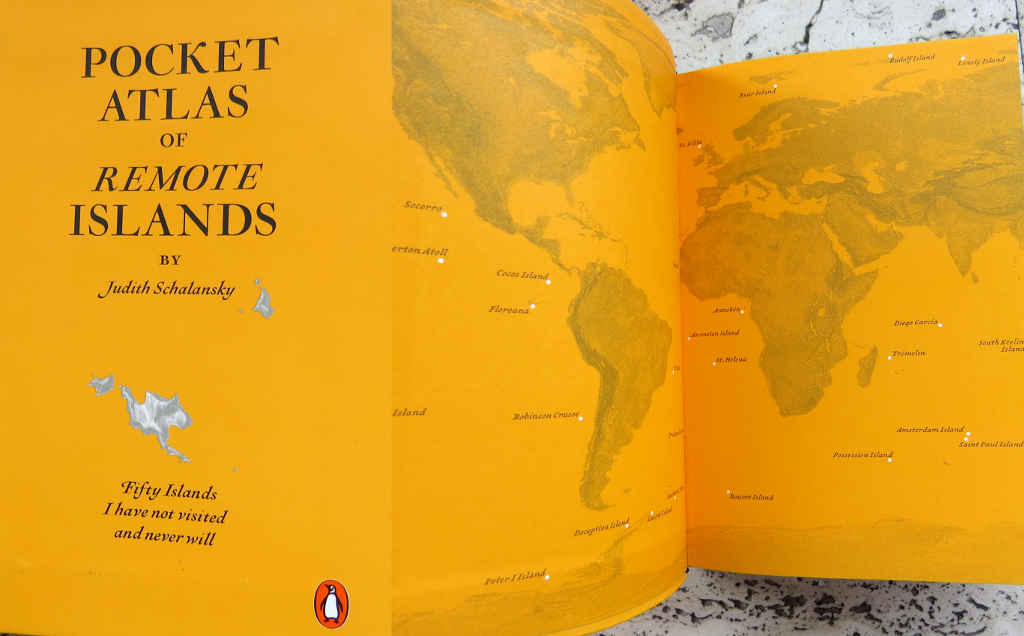

Pocket Atlas of Remote Islands:

Fifty islands I have not visited and never will

by Judith Schalansky

translated from the German by Christine Lo

published by Penguin Books

This is a most fascinating, delightful and beguiling book.

It is fascinating for the information it contains. In one sense, it is a gazetteer of fifty islands scattered about the globe with snippets of the stories – often just one story – and people associated with each. Fifty delicately drawn maps, all to the same scale. Brief notes on the islands, what they are called – or have been called – their allegiances (which states claim sovereignty), their physical sizes, populations or otherwise. And for each the distances from three other pieces of dry land at three different points of the compass, and the merest outline sketch of a timeline.

The book is delightful for its beauty and elegance. It is a pleasure to hold. The quality of the paper, the printing, the binding – the care that has gone into creating it. The typography and layout, the maps. The pocket version that I have is something you want to carry about with you. The full sized version would adorn any bookshelf.

However the Atlas of Remote Islands is also beguiling because of the clash it illustrates. The crash when the desert island paradise romance runs full tilt into the sometimes sordid, sometimes horrific, sometimes cryptic, sometimes heart-wrenching reality. Here are tales of castaways and disappointed explorers, mutiny and rebellion, insanity and corruption. Stories of rape, incest, murder and cannibalism. Accounts of lonely scientists and erotically disturbed merchants. The very title of the introductory essay is: “Paradise is an Island. So is Hell”. Don’t say you weren’t warned!

However the Atlas of Remote Islands is also beguiling because of the clash it illustrates. The crash when the desert island paradise romance runs full tilt into the sometimes sordid, sometimes horrific, sometimes cryptic, sometimes heart-wrenching reality. Here are tales of castaways and disappointed explorers, mutiny and rebellion, insanity and corruption. Stories of rape, incest, murder and cannibalism. Accounts of lonely scientists and erotically disturbed merchants. The very title of the introductory essay is: “Paradise is an Island. So is Hell”. Don’t say you weren’t warned!

In the introduction Judith Schalansky – a designer and typographer (of course), an author and a teacher – describes how, as a child born in East Berlin, she became an armchair traveller at an early age. How she used an atlas to explore the world she could never visit, until the fall of the Berlin Wall suddenly opened that world to her. But the reunification of Germany also revealed the insidious political agenda of the atlas.

The first atlas in my life… was committed to an ideology. Its ideology was clear from its map of the world, carefully positioned on a double-page spread so that the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic fell on two separate pages. On this map there was no wall dividing the two German countries, no Iron Curtain; instead, there was the blinding white, impassable edge of the page. That, in turn, the provisional nature of the GDR was depicted by the mysterious letters SBZ (Sowjetische Besatzungszone, ‘Soviet Occupied Territory’) in the atlases used in West German schools was something that I only found out later… Ever since then I have not trusted political world maps…

Of course, all maps are ideological. Flat representations of the world in atlases, projections of a three dimensional globe onto a two dimensional surface, skew the image of the world into something we are all familiar with and take for granted with barely a thought. Europe, that hard-to-delimit peninsular sticking out from the Asian landmass, is at the top and in the centre of the world map (unless you are in the USA in which case North America is top centre). The rest of the world is beneath, below, peripheral – with all that implies. And Africa, the world’s second largest continent, appears the same size as Greenland, which is in fact 14 times smaller. (I note that, for the endpaper maps of the world in this book, Schalansky has chosen what I take to be an equirectangular projection which avoids the Greenland/Africa distortion to some extent.)

Is a globe better?

The globe is certainly a better representation of the Earth than the collection of maps in an atlas, and it can rouse wanderlust in the young. But the shape of the globe is problematic. Constantly in motion, this Earth has no borders, no up or down, no beginning and no end, and one side is always hidden from view.

This is an approximate book. It contains the truth – “I have invented nothing,” says the author – but like an atlas, for all its apparent objectivity it is a subjective and partial report of these remote islands. An approximation. An interpretation.

And there’s a warning even in the title of the book. That little subjective word “remote”. What is remote, after all, depends very much on your point of view. Easter Island nearly 3700km from South America in one direction and a little over 4000km from Tahiti in the other is, from a European perspective, one of the most remote places in the world. The locals, though, call their island Te Pit Te Hunua – Navel of the World.

And there’s a warning even in the title of the book. That little subjective word “remote”. What is remote, after all, depends very much on your point of view. Easter Island nearly 3700km from South America in one direction and a little over 4000km from Tahiti in the other is, from a European perspective, one of the most remote places in the world. The locals, though, call their island Te Pit Te Hunua – Navel of the World.

In an interview, Judith Schalansky describes herself amused when she comes across her Atlas shelved by bookshops in their Travel section. I understand her. The book is more akin to poetry and/or philosophy – even geography – than it is to guide books. But at the same time, I understand the bookshops too. It is about travel; about travelling in the mind and the imagination.

So, the Atlas of Remote Islands – hard to categorise, but well worth searching out.

This article was written for the #Blogg52 challenge.

This review also published at Goodreads.com here: https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/1464082556

I published this originally at the separate Stops and Stories website. Transferred it here (after some editing for SEO), 2nd February 2017.