Recently my sister asked me to explain the difference between memoir and autobiography.

She’d been disappointed, she said, reading Elizabeth Jane Howard’s memoir Slipstream. She’d just finished the Cazalet Chronicle, Howard’s five volume novel series following three generations of a English family in the post-war years, and she wanted more. So she picked up Slipstream, only to find whole sections of Cazalet repeated in the book as if they really happened. She was confused. Was Cazalet fiction or was it fact? Was Slipstream an autobiography, or what was it?

I’ve not read either the Cazalet Chronicle or Slipstream, but that wasn’t going to stop me generalising. Besides, my sister rarely asks my advice about literature so I thought I ought to make a particular effort.

A working definition

Autobiography, I said, is when you write a biography about your own life and take on the role of biographer. In that role you are supposed to stick to the facts as far as possible, research your subject (yourself), and present as true an historical picture of your life as you can. When you write a memoir, though, you have the leeway to be more imaginative. For a fiction writer who has mined her own life for the material of her fiction, there’s probably a strong temptation to re-purpose that same material.

So my working definition: autobiography = true as you can make it; memoir = fictionalise as much as you like.

I can’t say I’m happy with that, and I’m not sure my sister was either. It’s good enough, but a bit too pat. So I thought I’d try and track down a better definition – and I disappeared down a rabbit hole.

The genres of memory

When you get authors taking themselves as their own subject, the text is even more likely to deviate from objectivity. And when it deviates a lot it becomes, what? Memoir? Faction? Autobiographical fiction? Autobiographical metafiction? Autofiction?

We humans do love to categorise our literature, don’t we? Is it fiction, fact or poetry? Are you writing an epic poem or free verse? Fantasy or realism? Romance or crime? As for factual writing, is it science you are writing or field guides? Are you writing how-tos or history? Political analysis or biography?

It seems that biography has always been a bit of a dubious field. Sure, there are biographers who make an effort to be objective about their subjects, but the crass truth is they often write about people who are famous or infamous. As a consequence, their biographies become hagiographies or, well, there doesn’t seem to be a satisfactory single word to describe a biography that demonises its subject. Diabolography?

On-line there is a mass of texts that are happy to give you definitions and examples that draw distinct lines. At any rate, lines that appear to be distinct. I see that autobiographies are “generally written in later life”, and they usually “look back over a whole life”. Memoirs, by contrast, are written about “shorter periods” and can be written “at any time in the author’s life”.

I also see that autobiographies are supposed to “stick to the facts”, while memoirs “focus on emotion” and “drama”.

Look closer and these distinctions blur. Autobiographies can be “enlivened by fictional elements” in order “to improve the story”. Memoirs also can be structured “to tell a better story”.

An aside on memoir(e)

The English word memoir comes from the French mémoire, but in modern French un mémoire seems to exist only as an academic term for what British universities would call a long essay or, perhaps, a Master’s thesis. This is the meaning that has brought memoir back into modern academic English, into the titles of academic journals: Memoirs of the American Mathematical Society, for example.

Much as I would like to believe this journal collects literary pieces about the emotional drama experienced by mathematicians in their lives, I suspect it actually collects mathematical monographs on abstruse subjects like field theory, combinatorics, dynamical systems and cryptography.

(I know nothing about mathematics. I picked those areas out of a list on Wikipedia.)

Sedaris to Erneaux – and Karl Ove’s struggles

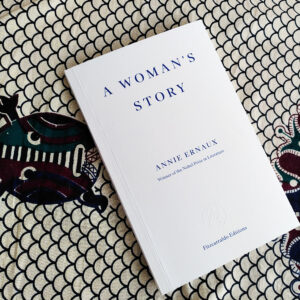

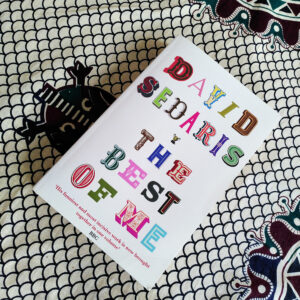

When I think of memoir and try to encompass the full range of what it can be, I must spread my arms wide. The fingers of one hand touch the books of David Sedaris on one side. On the other I can just reach the spines of my set of Annie Erneaux’s biographies.

Sedaris writes “ostensibly autobiographical and self-deprecating” stories drawn, he claims, from his diaries. Annie Erneaux writes meticulously researched accounts of her own life, and of the lives of her parents, into which she occasionally inserts herself as the author describing her method and struggles with objectivity.

The term autofiction has developed in recent years (since the late 70s, says Wikipedia) and “has parallels with ‘faction’, a genre devised by Truman Capote” of In Cold Blood fame. A modern practitioner is the Norwegian author of My Struggle, Karl Ove Knausgaard.

The way the term is used tends to be unstable, which makes sense for a genre that blends fiction and what may appear to be fact into an unstable compound. In the past, I’ve tried to make a distinction in my own use of the term between autobiographical fiction, autobiographical metafiction, and autofiction, arguing that in autofiction there tends to be an emphasis on the narrator’s or protagonist’s or authorial alter ego’s status as a writer or artist and that the book’s creation is inscribed in the book itself.

Christian Lorentzen, “How ‘auto’ is ‘autofiction’?” Vulture, New York, May 2018

Memoir and autobiography

Honestly, I don’t know where this gets us. Not any closer to a clear distinction between any of the genres in the fiction/non-fiction/auto/biographical/memoir field, that’s for sure.

Maybe we must just accept that authors are a bunch of storytellers whose principal activity is to entertain. (Themselves at least.) They will do that in whichever way and with whatever material is available. And invent or bend the definition of genre terms to cover themselves after the fact.

Notes and sources

The websites and pages I visited for this included several dictionary sites, Merriam-Webster’s being one, the Cambridge Dictionary being another. Grammarly, Masterclass, and Blurb all fed into it, and Wikipedia (1, 2, 3, 4) of course.