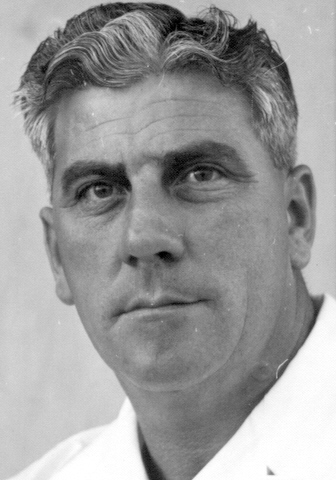

On and off last week I spent quite a lot of time thinking about my father. It was his birthday on June 21st, and had he lived, he would have been 89. In fact, he died October 1995.

A bad journey

Early in the summer of that year, I took myself from Warsaw (where I’d been working) via Berlin and Hook of Holland to my mother’s in the south of England. On the way, I think in Berlin, I picked up some sort of stomach bug. It was some sort haemorrhagic intestinal variant of E. coli, no doubt. At one point it had me shitting blood. It was a very unpleasant journey and I was very relieved when I finally reached Mum’s.

A couple of days after I arrived, while I was still recuperating, I received a phone call from my father. “I hear you’re not well,” he said. “I bet you’re not as bad as me!” There was something almost bragging about the tone of his voice, but also something else which I realised after must have been fear. He’d been admitted to hospital in Tunbridge Wells, where he lived, and initially diagnosed with jaundice. But then the doctors realised he had a cancer in his pancreas.

For many years I believed I was a very grave disappointment to my father. Now I’m not so sure. I don’t think he was so seriously disappointed in me, because I’m not sure that he was particularly interested in having a son in the first place. It’s not entirely impossible that he married and had children because he wanted to prove to himself, to his friends, to his father, that he could.

Ball sense

I doubt that was good enough for Harry, my grandfather. Dad could never live up to his brothers who both died in the war. On the other hand, it’s true, he was the only member of the family to produce a son. But what kind of a son? I now believe that, having absolutely no ball sense, I was a huge puzzle to my father.

Dad was one of those people who are born with an innate sense of what to do with any given spherical object, and how to do it. He could play any ballgame with minimal practice: he played football, tennis, golf and cricket, and he played them well. He was a good player, but he was a terrible teacher. Since he’d never had to make an effort to learn, since it had always come naturally to him, he had no appreciation that another person could not learn as easily. And he was completely incapable of teaching his skills to anyone else. I didn’t inherit his skills. I couldn’t learn from him (or, indeed, from anyone), so we had no common ground.

Mum told me later that Dad’s ambition was to coach a professional football team. If he’d ever got a job like that, I don’t think he’d have lasted long.

A young man’s game

My father was a transport engineer. He learned his trade in the army during the war. His army years in North Africa and Italy gave him a taste for life in warmer climes than England. Throughout my childhood he spent much of each year abroad. Sometimes he stayed abroad for two or three years at a stretch. He worked in the Middle East and Africa on major industrial engineering projects and so was more absent than present during most of my childhood. I knew him from when he was home on leave, or from those times when the family lived abroad with him. When I was two years old we lived in Qatar for a year. And when I was six we spent nine months or so in Ghana.

But working abroad as an engineer is very much a young man’s game. Eventually Dad got to the point where he could no longer get new contracts. Towards the end of his active life as a travelling engineer, I remember him living for longer and longer periods with us at home in England. I see now that he must have been terribly depressed.

He went to the pub and talked large. (He was always a social man. Could strike up superficial conversations with almost anyone.) He drank, he came home and sat in front of the TV and fell asleep. In the summers he might take my sister and me and drive around the countryside. Or take us to a playground somewhere and leave us while he sat and watched a local cricket match. But mostly he sat at home in front of the TV and watched the sport and slept. His last job abroad was a six week contract in Libya, which he hated.

Maidstone or Brighton

He began to look for work in England. Eventually he found a job working in middle management for a bus company in Kent. It was based in Maidstone; we lived in Brighton in Sussex. The towns aren’t that far apart on the map, but the daily commute would have been wearing. While he’d been abroad, the companies he worked for had paid him well and he’d been able to live there – in Kenya, or Saudi, or Zambia or wherever – and pay for our home in England. That was no longer an option. Now he wanted us to move with him from Brighton to Maidstone.

Both my sister and I were settled in the secondary schools we were attending, after rather erratic experiences in primary school. My mother was not keen to move us. I remember a couple of visits to Maidstone to look around, but nothing came of the move.

I don’t think Mum and Dad were ever really compatible. Their marriage held together for so long mostly because they didn’t actually live together. Now they had to live together, the strains were too great.

This is where the acrimony crept in – or perhaps it didn’t creep so much as leap. If they were to separate, then my father thought he was entitled to the value of the flat where we lived. After all, he had paid for it. My mother, however, had managed to get both their names written into the ownership contract. This was a precaution after my father sold our previous home without telling her. (We spent a couple of months sharing a room in a boarding house.)

Property

The next five years were very difficult as Dad’s lawyers and Mum’s skirmished around the issue. Eventually, after five years, they were able to divorce. The settlement left my mother in possession of the flat for as long as one of us children was still studying at college. So when my kid sister completed her university studies in London, Mum had to sell up and half the profit was paid to my father.

In Kent, Dad had taken up with a woman called Doris. Eventually he lived with her longer than he was married with Mum. They were far more suited, Dad and Doris. Towards the end of her life, though, Doris became senile and very, very repetitive. It drove Dad crazy to the point where he walked out on her. He disappeared completely for a number of days. It seems that he took his car and drove down to the West Country. He eventually returned. I’m not sure if he was tracked down by the police or if he returned of his own free will. But he could no longer live with Doris. He managed to find a one-room flat in a small complex of sheltered accommodation for elderly people (he was 75 now) and it was from that flat he was taken into hospital when his pancreatic cancer was diagnosed.

Dad towards the end

Once I’d recovered from my own illness, I realised that I had nothing else of importance to do that summer. Rather than return home to Sweden I moved into Dad’s place in Tunbridge Wells and lived there for the rest of the summer, going up to the hospital every day to see how he was. It was the longest extended period of time that I had ever spent in his company.

He was very yellow and very weak and we couldn’t actually spend much time together, but the time we had, we talked. Mostly, we talked about his memories of the places where he had lived when he’d been happy, especially about East Africa. The times I remembered vividly – especially the nine months in Ghana – he had little memory of.

He was very yellow and very weak and we couldn’t actually spend much time together, but the time we had, we talked. Mostly, we talked about his memories of the places where he had lived when he’d been happy, especially about East Africa. The times I remembered vividly – especially the nine months in Ghana – he had little memory of.

He was still alive at the end of August when I had to return to Sweden to work, but he died in October and I flew back to England for the funeral. After saying goodbye in August, I didn’t see him again. I didn’t manage to get to the funeral home before the coffin had been sealed.

I never expected Dad’s death to touch me as much is it undoubtedly did. It was disturbing to realise, looking back after a year or so, how much his death had affected me. I suppose to some extent the impact it had was more to do with the loss of somebody in the generation ahead of me, somebody close, and the feeling that I was now in the front line. That Time was breathing in my face.

A life in compartments

At the same time his death, and the time I spent with him in hospital, caused me to re-evaluate our relationship and also to look back again through his life and see it to some degree with new eyes. I was responsible for writing his eulogy for the priest to read. (Dad had a conventional Church of England crematorium ceremony.) I came to realise how much he had compartmentalised his life. He had kept up very little with people from earlier phases in his life. The only person we were able to find who knew him as a boy was too ill to attend the funeral, and I could find no one from his days in the army.

Dad had almost no papers or other records from his early life. The earliest photograph we found among his possessions was one of him when he was in his 30s in a cricket team in Saudi Arabia. He had kept his war medals, but that was about it.

When I was a child, I felt inadequate by comparison to him. I was so different from him, I had such different interests and skills. In many ways I was more my mother’s child than I was his. And yet physically, I resemble him. I have his build, I walk the way he did, my hairline is the same as his was. I’m clearly his son.

Good and bad parenting

I think that I intimidated him to some degree, especially later in life when I went to university. And I’m absolutely sure that he didn’t really know how he should behave towards me. I think he was a lousy father, and I’m fairly sure that he thought so too. (Though he may have felt he was a better father to me than his father had been to him.) On the other hand, I’m not sure that I was such a good son. Perhaps, had I been a better ball player, he would have been more interested in me and more able to relate to me. Perhaps if he’d been able to show some appreciation of me, I would have been a more loving son.

Well, anyway, at this time of the year, every year, I find myself thinking about him again, so his influence is still hanging over me. And of course, since I resemble him so much physically, I occasionally wonder whether I’m going to make it past 75 myself. To be sure, I don’t smoke, which is certainly a mark in my favour. Dad was a Player’s Navy Cut Full Tar man. Harry Nixon, Dad’s father (a non-smoker), lived into his 80s, and if I have enough of my mother’s genes in me, I might be able to look forward to another 25 years. She will be 90 next year.

I have no children. Part of the reason is probably a subconscious decision that generations of poor parenting would end with me. But I begin to regret it, even though it means that in 40 years time, or 50 or however many, no one will be writing something like this about me.

More posts about Dad, and one about Mum:

The Ghana Christmas Ball and my Father Christmas

The powerful and difficult relationship with our father!! It’s a lovely tribute, John. We are meant to be different, every single one of us, and to return to love. That’s what you do here while facing your own mortality. And someone else will write about you one day. A close friend, someone you love, don’t worry about that! 🙂

Thanks for sharing!

Thanks Maryse. This one turned out a bit longer than I intended … I appreciate that you read it through to the end!

Thanks, Alexander. I’m glad you liked it.