At Pens Around The World, every other week, one of us publishes a Pensive. A prompt or collection of prompts to get us writing. Last week Kimberly Hirsch gave us a Pensive that revolved around significant or formative events.

One of these coupled itself with thoughts of my father that always come back at this time of the year. His birthday was on 21st June. Had he lived, he would be 99 years old now.

Kimberly’s prompt was: Write yourself a rejection letter from any point in your life. Give yourself some feedback on it and suggest the next steps.

A letter from my father

I’m not sure this counts as a rejection letter, but it’s a letter my father might have written.

Dear John,

Thank you for the card. And the birthday wishes. They read well. You always had a way with words. Don’t know where that comes from. Your mother I suppose. You were always reading. Glasses on your nose. Nose in a book. Whenever I came home. Why couldn’t you ever play cricket? Football even? Do you remember when I took you to a cricket match? You wandered off. We had to call the police. Another row with your mother. Found you in a library. Anyway. I’m glad to hear you’re settling in over there. I don’t know much about Sweden. Never been. I was always an Africa-hand. Palms beat pines. In my book. Your stepmother. I mean Doris. She wants me to say you should come. Next time you’re in England. You can bring some cigarettes.

Love, Dad

Dad’s gifts were not literary and we rarely discussed his memories of my childhood the few times we met as adults. But he did write letters like this, to me and to my sister, and I’ve tried to imitate his style and erratic employment of the full stop.

Blue airmail paper

I don’t mean to imply that he was illiterate, because he wasn’t. He read, mostly thrillers and historical adventure stories, and introduced me to Hammond Innes, Alexander Maclean and James Clavell. I remember him reading aloud (to Mum rather than to us children), The Darling Buds of May by HE Bates. But he didn’t write letters habitually and after he retired he didn’t really have occasion to, except when replying to birthday cards and Christmas cards.

For some years, throughout my later teens and twenties, he would always write on blue Basildon Bond airmail paper. The onionskin pages would come out of the envelope thin and a little crinkled. Often the point of his ballpoint would have puncture them, especially when he wrote a full stop. You could hold the page up to the light and see pinpricks of brightness like a secret code scattered across the page. Later he switched to regular white letter paper that stood up to his full stops more successfully.

I wonder if, working abroad, he’d built up a store of airmail paper that he used up before switching to more conventional letter paper.

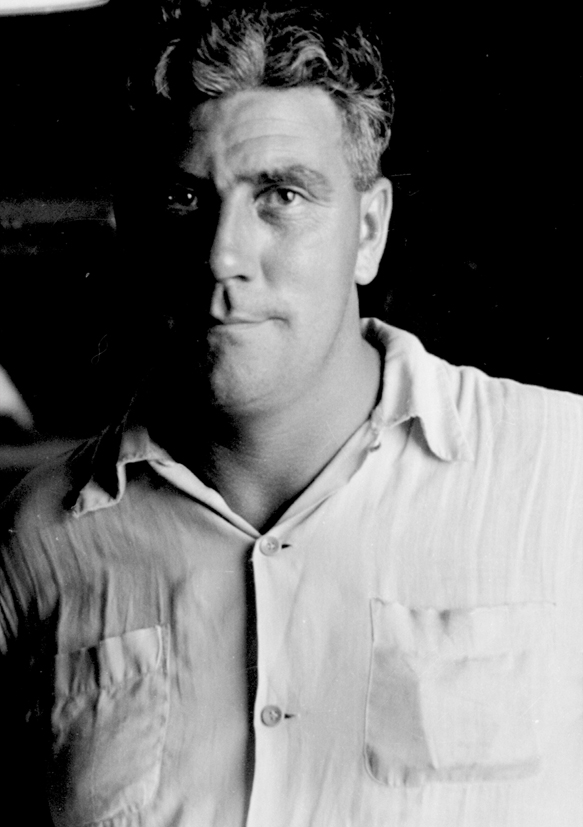

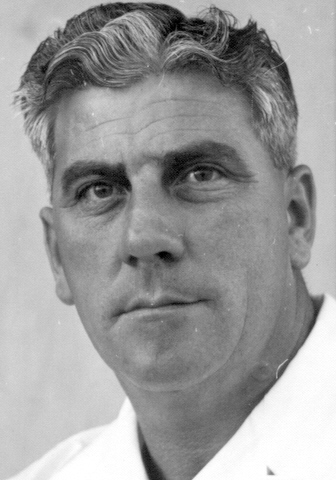

More about this photo here.

Army runaway

Dad ran away from home to join the army in 1937 or 1938. (He may have lied about his age). So he was a regular recruit on a 9 year contract when he took part in the Second World War. In the army, in the war, he learned his trade, mechanical engineering (servicing tanks I suppose), in North Africa and Italy. He finally demobbed in Austria in 1946. After that he did engineering jobs for big multinational companies on the oilfields and on prestige projects in the Middle East and Africa. When he could no longer get work abroad, he moved home to England and was pretty much a stranger in our family.

My parents separated when I was 13 and then divorced when I was 17 or 18. After that I didn’t see much of him except the occasional summer visit to his home in Kent. He took up with a widow, Doris, and though they never married he ended up living with her longer than he ever lived with my mother.

In the summer of 1995, I reached England to stay with Mum after crossing Europe from Poland where I’d been teaching in a summer school. I managed to pick up food poisoning on the way and was feeling very sorry for myself. Dad phoned me at Mum’s. “I hear you’re ill. I bet I’m worse.” He was. He had been admitted to hospital with jaundice, but they diagnosed him with cancer of the pancreas.

In hospital and ball games

Unusually, I had nothing else to do that summer, so I was able to stay in his flat in Tunbridge Wells. (He’d separated from Doris by this time.) I visited him every day in hospital and sometimes I held his hand. It was the closest I’d been to him all my adult life. I don’t think we ever overcame the barriers between us, but I’m glad I was able to do that.

I always felt I was a disappointment to him. Mostly because I couldn’t play ball games, while for him ball games came so naturally he was incapable of teaching me (or anyone). Cricket was his favourite sport, but he played tennis, football and rugby. In later life he played a lot of golf.

He was still alive when I had to return to Sweden to work. He hung on a couple of months, finally dying in October. My sister, who was living in London, took over responsibility for him. She ended up doing all the hard work of sorting out his estate, such as it was, and organising his funeral. But after he died, I was able to take time off teaching to fly back to England for the service. I was delegated the job of writing Dad’s eulogy.

Compartmentalised

It was a surprise to find how compartmentalised he had made his life. After he’d lived a period, he would close off that time. Seal it, and move on. I only found one person who knew him as a child, and no one from his time in the army or in his various engineering jobs abroad or in Britain. I’ve no idea what he went through in the war, he never talked about it.

Is this a common experience, I wonder? To have a parent you think you know simply because they are your parent, and to discover you really know very little about them after all. In his flat he had almost no photos. The earliest one we could find was a framed picture of himself with a cricket team in Saudi Arabia. The early 1950s we think. No mementos but for his war medals, and they were the simple service medals you’d expect.(Thieves took both the picture and the medals from my storage locker after a break-in a few years later, so I don’t even have them any more.)

Next steps?

Kimberly’s writing prompt concludes: suggest the next steps. I’ve been brooding over this for 26 years now. (Read the post I wrote about Dad 10 years ago – linked below – and you’ll see what I mean.) I don’t know what my next steps might be. Suggestions?

[And, yes, I do know the conventional meaning of a “Dear John” letter. This is what passes as a joke among us Johns.]

Good one!

Thanks Bruce!