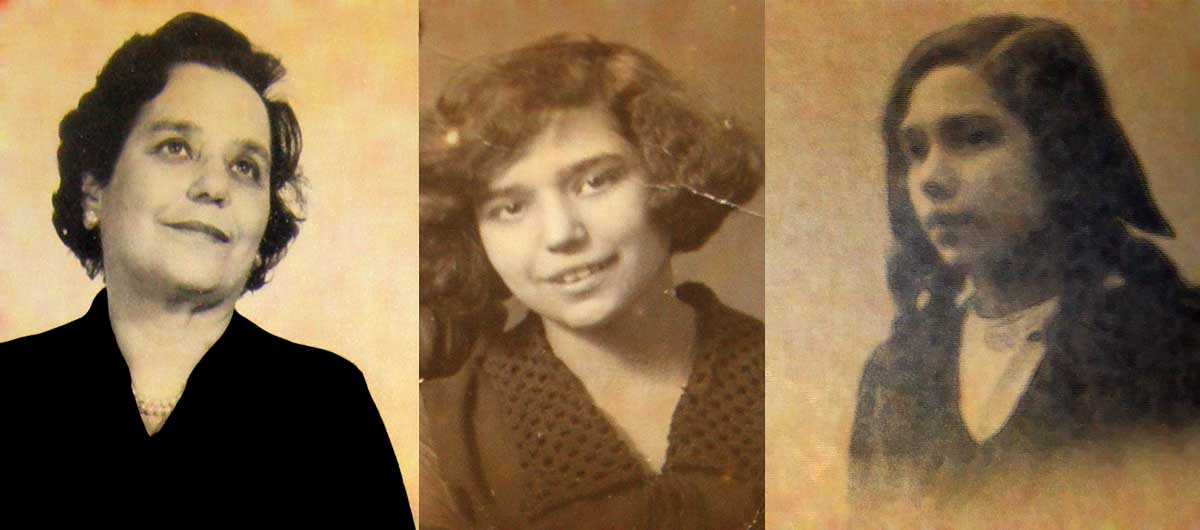

Deborah Warwick – Debbie – was my grandmother. My mother’s mother. For thirty-three years we shared a birthday, 30th July, and I think of her every year on this date – and on the days around. She was “as old as the century”, as she liked to say, and died at 92 nearly thirty years ago. I still miss her.

Economic refugees

Grandma was born, presumably in 1900, in Odessa. The Black Sea port was then a part of the Russian Empire. Her birth name was Teborah and her family name (this is a guess) was Jelesnek or Jelinek or something similar. While she was still a baby, to escape the pogroms, her family crossed Europe illegally to make a new home in England. Economic refugees, they’d be called today.

The family changed their name in England. They became “Jimack”. I think it was a way of making their name more easily pronounced in English. It means that I’m almost sure every Jimack in the world is a cousin of some degree.

Exactly when they came to England is a bit of a mystery. Grandma always claimed she “remembered seeing” Queen Victoria’s funeral procession. That would have been at the beginning of February in 1901. She would have been about 6 months old, so I have my doubts about the remembering. But she could have been taken to see it, either in London or perhaps in Portsmouth.

The family lived for a time in Southampton where Debbie’s father had found work in a sweet factory. Queen Victoria died at her palace on the Isle of Wight and her body was brought by sea to Gosport near Portsmouth, then taken in procession through the streets to the railway station for onward transport to London. Crowds turned out to witness the cortège pass, both in Gosport and, later, in London.

Karl Marx

Assuming the Jimacks were in England in 1901, they successfully managed to avoid being counted in the 1901 census, taken in March. Understandably, as they were illegal immigrants. They were certainly in the country in 1902, though, because the 1911 census (which they didn’t avoid) identifies Debbie’s younger brother David as born in Poplar in London’s East End in 1902. The same census records Deborah Jimack as 11 years old, born in Russia and attending school.

Grandma left school at 14. It was normal at the time. We know she worked in a cigarette factory. (Cigarettes were becoming fashionable.) She also worked in a shop where, in her telling, the boss claimed to be shocked that she hadn’t read Karl Marx. His teasing, if that’s what it was, sent her off to find a copy of The Communist Manifesto, after which she became a political radical.

I have questions about that story too, but it was the story she told.

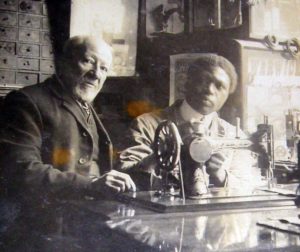

In 1922, in Lancashire, she married an Englishman. Known in the family as Charles or Charlie B, Charles Bradlaugh Warwick came from a Manchester Liberal family. His father, supposedly, founded a factory to make sewing machines. The Warwick sewing machine according to family tradition. There’s a photograph of an old man teaching a young African man how to use it. Charlie made a note beside the photo to identify the old man as Charlie’s own grandfather

Sadly, the only information I’ve been able to find about the Warwick sewing machine suggests a different manufacturer. Also, the 1901 census which is the first to feature Charlie B identifies his father’s occupation as Sewing Machine Fitter.

From Teborah Jimack to Deborah Warwick

Still, the Warwicks, if not middle class factory owners were probably upwardly-mobile working class and on the educated, radical end of the political spectrum. Charles, their eldest son, was named for Charles Bradlaugh, the first atheist Member of the British Parliament. Charlie’s brothers were William Morris Warwick (after the Pre-Raphaelite artist and socialist associated with the Arts and Crafts Movement) and Sidney Shelley Warwick (after the poet). Perhaps in teenage rebellion against his family, Charlie B placed himself as far to the left as he could. (I’ve found him on-line described as an anarchist.) It was through their mutual, radical interests that Debbie and Charlie met sometime in 1920.

I’m sure they loved one another at the beginning, but both had mixed motives for their relationship. Charlie was fascinated by Grandma’s Russian (read radical Communist) roots. Grandma wanted a marriage to make her status in England legal. Given that their marriage is recorded at Chorlton in Lancashire in 1922 (“April-Jun 1922”) and Mum’s birthday is 15th March, I’m going to guess the baby’s arrival was what precipitated the marriage. That chimes with some stories I’ve heard from Mum about Charlie’s family putting pressure on him to make Debbie “an honest woman”.

As a married couple, the two split their time between Manchester and various Jimack homes in London’s East End. According to my mother, this was entirely a consequence of Charlie’s wandering affections. He would become “infatuated with some young thing”. Debbie would leave him, taking her daughter, and return to London. After Charlie’s infatuation had run its course, he’d come down to London and plead with Debbie to come home. Which she would do. And then the whole business would repeat.

Ivinghoe and the war years

In the 1920s, Charlie and Debbie joined the back-to-the-land movement and ran a market garden outside of Manchester for several years. Mum always said of her father that he could make anything grow. Later, Grandma became the warden of a youth hostel in Ivinghoe in the Buckinghamshire countryside north-west of London. It was during this period the marriage finally failed. Because the Ivinghoe Youth Hostel was Debbie’s job, she couldn’t leave Charlie when his eye started to roam. Instead she sent him packing.

That was the end of that. Various Jimacks reported seeing Charles in and around London or Manchester, but Mum only saw her father again once. It was during the war when she got dispensation from her service to visit him in Manchester (at his request). After that, nothing. The family assumed he remarried – but he never divorced Debbie.

Grandma’s time as a single parent and hostel warden was successful and happy. (At least Mum was happy to live there in her teenage years.) But in 1939 the war came and, soon after, the Youth Hostels Association closed Ivinghoe down. Grandma found work in a machine shop, turning metal on a lathe. “War work,” she said.

Later, towards the end of the war and into the late 40s she was a housekeeper in a London hospital, overseeing in particular the laundering of bedclothes. (Years later, she still had a cook book from the hospital with recipes that involved huge quantities of various unappetising ingredients.)

Not a ballerina

My mother, meanwhile, applied to join the Womens’ Auxiliary Air Force, the WAAFs. She was accepted the second time she applied. After Russia had entered the war on Britain’s side in 1941. Mum believes her earlier application was rejected because of Debbie’s original nationality. Mum was 21 and a trained secretarial assistant. She really wanted to be “doing something exciting,” she says, but the war effort needed secretaries, so that was what she spent her war doing.

It’s amusing to read the following, at the end of the footnote to Charles Bradlaugh Warwick on the Libcom.org website. “Married a Russian Jewish woman [… f]rom whom he later separated. Joined the Communist Party. [… Reported] to have had a daughter who was a ballerina who danced at Covent Garden.” I’m absolutely sure it was Mum’s dream to have been a ballerina and dance at Covent Garden, but it didn’t happen. Still, it makes me wonder where the author got his information.

After the war, Mum and Debbie moved to the south coast. I think they may have followed friends, or followed Mum’s job. Mum married my father in 1957. He was a Brightonian from a solid, middle-English background. Neither Mum nor Debbie told him about Grandma’s Jewish ancestry, perhaps because he was a man who easily used racial slurs. I find it difficult to believe he never understood what Grandma’s origins were, but I suppose my Mum’s blonde hair and blue eyes, inherited from her father, were a pretty good disguise.

Slow on the uptake

To be fair to Dad, I was in my twenties myself before I joined the dots. One day I asked Grandma, “Are we Jewish?”

“You took your time working that one out,” she said.

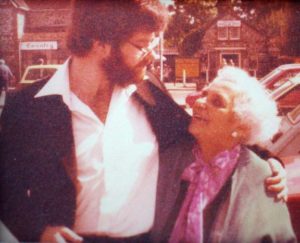

In 1986, soon after our joint birthday in August, I visited her with a cassette tape deck. It wasn’t something I planned in advance. I had the deck – it was my sister’s – because I’d picked it up from a repair shop and was taking it back. I also had a blank 90 minute cassette tape. So I decided to test the cassette deck by recording Debbie while I got her to talk about an album of photos and postcards that had always fascinated me.

On the album’s title page Charlie B had written “Rebels and Ramblers”. He put the album together some time in the 1920s. Grandma was happy to talk, even after she realised I was recording her.

Grandmother’s voice

A few days ago I rediscovered the cassette in a box in the attic. Of course, I no longer owned equipment to play a cassette tape, but I bought a player on-line. Now, as I write I’m copying the tape to a digital sound file, but I’ve already listened to a part of it. I get a bit teary-eyed hearing Debbie’s voice again, thirty-four years on.

Gran’s last couple of years were not great. She was sinking into dementia – phoning Mum at all hours, confused about the day and the time. She had a fall in her kitchen and lay on the floor cold and unable to get up for we don’t know how many hours. After that it was only a matter of weeks before the end. The last time I saw her alive, she looked so small and frightened in her hospital bed. I don’t think she recognised me.

Gran wasn’t religious. Before she lost the ability to decide, she made sure she she was a fully paid up member of the British Humanists. She wanted to be sure of a secular funeral. And that was what she got. In February 1992, in a non-denominational chapel at Brighton. And after her cremation, we buried her ashes and planted a rose bush over them in the Garden of Remembrance at Brighton’s Cemetery on the downs above Woodingdean.

A life, a death and a memory, bridging three centuries – just about.

Interesting story. She seems to have been a Very strong person.

Thanks for reading and for your comment, Laila.

Yes, I think in many ways circumstances called on her to be strong, and she grew in strength to meet them.

Å, vilken fin berättelse om din mormor! Jag har ett vagt minne av hennes bortgång, men vi bodde ju inte i samma stad då.

Ofta tänker jag att jag ska skriva historier om min släkt, men jag har inte kommit särskilt långt.

Tack Lena!

Jag håller på att dödstäda – tydligen. Vi började med att rensa bland Agnetas mammas saker, men sen fortsatt jag med alla mina låder i vinden. Det var så jag hittade inspelning som jag skrev om i inlägget. Att höra mormors röst igen, så nära intill våran gemensam födelsedagen, påminde mig om hennes historia och fick mig att vilja dela den.

Hi John,

I only just noticed that this post is from 2020, all the same, I really enjoyed reading about your grandma. Well told!

debbie

Thanks Debbie!