This second reading quarter got off to a shaky start. I only managed to completely read three titles in April (and one of those was a fat book I’d been reading for most of March). However, by the end of June I’d completed 14 titles putting me on good course to achieve my 50 titles target for the year. I missed reading on fourteen days (eight of them in April). What follows is a potted review of the highlights, from Londoners to The Incandescent Ones by way of Beckomberget and a Small Angry Planet. There’s a complete list of the fourteen titles at the foot of this post. Click here to jump directly to the book list.

Londoners

The days and nights of London now – as told by those who love it, hate it, live it, left it and long for it. That’s the subtitle and it’s a better summary of this book than anything I could come up with myself. The book contains around 80 extracts from interviews author Craig Thomas made with Londoners over a 10 year period.

The transcripts are divided into neat sections: Arriving, Getting Around, Seeing the Sights, Living and Dying. A couple of the interviewees come back more than once – Smarty the cabdriver with a wealth of stories about the London he grew up in; the airline pilot whose pictures of London from the air bookend of the book. Otherwise this is a kaleidoscope of voices and stories and ideas. An oral history and a snapshot. It captures the essence of London as it was in the first decade of the century. It’s a fascinating read that I first read in 2015. I enjoyed it just as much re-reading it now, though I do find myself wondering how different London is in the 2020s. How a new edition with new interviews would differ.

Londoners and The Art of Dramatic Writing are my two non-fiction titles from the quarter. I wrote about Lajos Egri’s writing craft handbook in an earlier post, linked here. Between the two, and overlapping with them to some extent, I read two more imaginative novels. These were The Long Way to a Small Angry Planet by Becky Chambers, and Nancy Stohlman’s After the Rapture.

A Long Way …

The title of Becky Chamber’s novel is just as descriptive and accurate as Londoners‘ subtitle. Planet tells you it is science-fiction. The adjectives Small Angry (as applied to a planet) tell you the story is a comedy. Long Way lets you know this is a road trip that focuses on the journey rather than the destination.

The Wayfarer is an engineering spaceship that works to construct hyperspace tunnels to enable interstellar travel. The crew are a mix-match of humans and aliens, born on different worlds from different backgrounds and cultures. Becky Chambers (a Californian) goes to some lengths to make sure everybody on the Wayfarer uses appropriate pronouns, which seems more reasonable in this context than, perhaps, in 21st-century California. For the first time I see “xe” used as a pronoun where (for me) it actually works.

… to Rapture

Long Way is a light read. Nancy Stohlman’s After the Rapture isn’t heavy, and it’s very funny in places, but it is more serious and more challenging. It also a lot shorter. It is a novella composed of dozens of short, flash fiction stories that interlock to create a fever-dream image of US society turned in on itself and imploding under the force of its own vacuity. Barbie and Ken, kareoke shootouts and popcorn financial bubbles. The evangelical Christian obsession with apocalypse (the Rapture) and the Antichrist. The novella’s protagonist finds herself confused and conflated with Barbie. She is mistaken for the Antichrist, is the victim of a car crash – real and metaphorical – as US society folds in on itself and around her.

The book is a kaleidoscopic picture of a mad world where individuals still struggle to maintain a little dignity, remain self-aware, look for a life after the rapture. And so it is a book that ends in hope, looking forward to a time when dreams are no longer nightmares.

Beckomberga

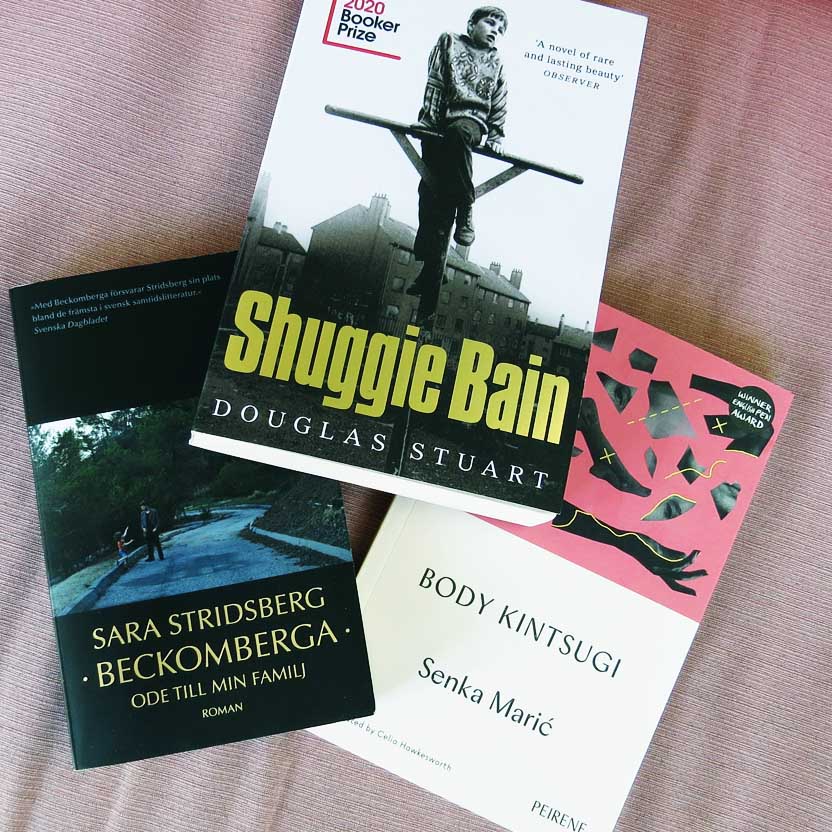

Every quarter I try to read at least one novel in Swedish, and Sara Stridsberg’s Beckomberga is this quarter’s.

Beckomberga is a family saga of sorts, and the story of the mental hospital at Beckomberg outside Stockholm. The hospital operated between 1932 and 1995. The core of the family, Jimmy, Lone and their daughter Jackie (who is the principal protagonist and the “I” of the novel) are all linked to the hospital. Initially this is because of Jimmy who is admitted because, while drunk, he tries to kill himself. He is an alcoholic. Lone brings Jackie out to the hospital when she visits him there. Later, Jackie visits under her own steam, when Lone leaves her to travel the world. (Jackie is 14.)

The novel interweaves the stories of Jackie and Jimmy, of Jimmy’s mother and father, of his lovers and his medical providers (who are also suspiciously using him – or being used by him – for drugs, drink and sex), and of Jackie and her son. All these stories are told in fragments of happenings, memories, dreams or dialogue. Interspersed throughout the book are short chapters given over to Olof, who is the last profoundly institutionalised patient in the hospital and is discharged in 1995.

The story is beautifully told and fascinating for the way it seems to sidestep the usual structure of the novel, but still tell a gripping story, and do it in lyrical language and images. A recurring motive is the seagull that flies down a corridor in the hospital. Is this a real event, something that happened once the hospital was abandoned? Or is it something Jackie dreams?

Complicated families and tortured lives

There was a block of novels towards the end of the quarter that told complicated family stories. Apart from Beckomberget, Senka Maric’s Body Kintsugi told the story her protagonist’s struggle with metastasising cancer in the shattered world of former Yugoslavia. Journeys from doctors and hospitals in Bosnia to Croatia and back. Shuggie Bain is Douglas Stuart’s fictionalised account of growing up gay and working class in 1980s Glasgow. Hot Milk is Deborah Levy’s novel about a mother and daughter relationship in which the mother’s illness (which may be psychosomatic) impacts on her daughter who is discovering her own sexuality in a sun-drenched Mediterranean littoral.

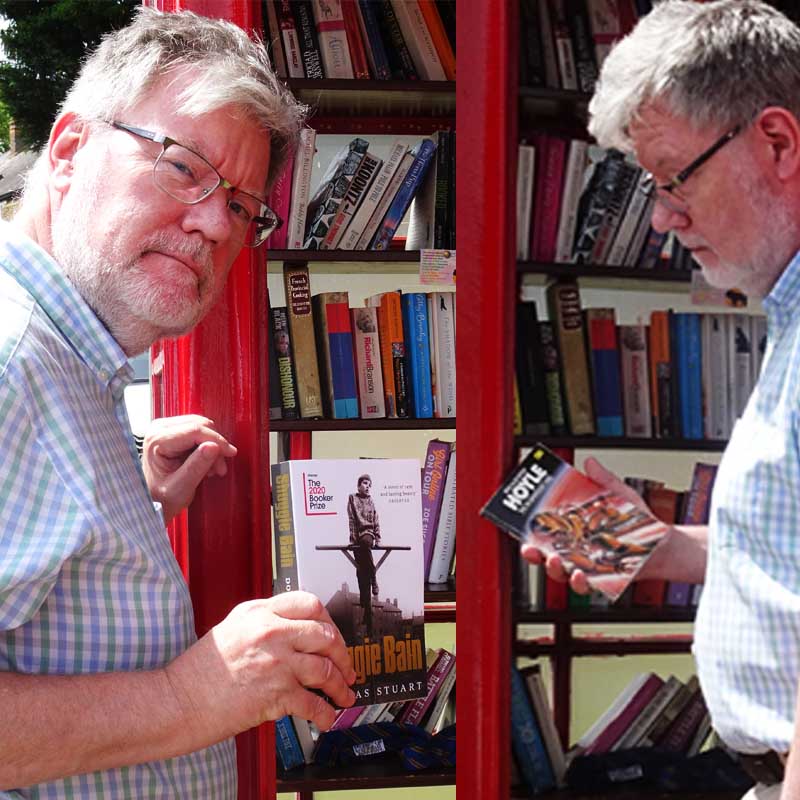

Shuggie Bain, really dragged me down. After I finished it I needed something much less intense to buoy me up. At that point I was staying with my sister in England, so I raided her bookshelves and found Elizabeth Strout’s Oh William! and Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus. Both of these in their way told family stories, but they were much less distressing and Lessons in Chemistry was very entertaining.

In my sister’s village there is a book exchange set up in what used to be the village’s telephone box. I took Shuggie Bain along to leave there and swapped it for something completely different. The Incandescent Ones by Fred and Geoffrey Hoyle.

An incandescent ending?

Published in 1976, The Incandescent Ones is “hard SF”. I suppose that’s what you’d call it. As far as I can remember I’ve not read any SF by the Hoyles before. After this one I’m not encouraged to read more. Not that it was a bad story or badly told. On the contrary, it has a driving force to it that swept me along. Much like a downhill skier, off piste, racing ahead of an avalanche. (Actually something that happens in the story.) But the dramatic shifts from what starts out as basically a spy novel, to solid science-fiction (a space flight to Mars), to quantum mysticism in the vein of Arthur Clarke’s 2001 a Space Odyssey, and with virtually no character development, left me cold.

But I was travelling home from England at that point and I would have read anything.

So that’s my quarter. Not all the books reviewed, but the highlights. Have you read any of these titles or authors? What did you think?

Book list

(The books are listed in the order in which I finished them.)

- Londoners by Craig Taylor (oral history, 436 pages, read in 19 days)

- The Long Way to a Small Angry Planet by Becky Chambers (SF novel, 404 pages, read in 9 days)

- After the Rapture by Nancy Stohlman (novella composed of flash fiction pieces, 115 pages, read in 4 days)

- The Art of Dramatic Writing by Lajos Egri (non-fiction, writing craft, 316 pages, read in 17 days and then re-read for notes)

- The Rising Tide by Anne Cleeves (detective novel, 374 pages, read in 10 days)

- Sea of Tranquility by Emily St John Mandel (SF novel, 255 pages, read in 5 days)

- Grimble by Clement Freud (illustrated children’s storybook, 44 pages, read in 3 days)

- Body Kintsugi by Senka Marić, translated by Celia Hawkesworth (novel, 165 pages, read in 6 days)

- Beckomberga: ode till min familj by Sara Stridsberg (novel, 366 pages, read in 8 days)

- Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stuart (novel, 430 pages, read in 10 days)

- Oh William! by Elizabeth Strout (novel, 240 pages, read in 2 days)

- Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus (historical novel, 400 pages, read in 5 days)

- Hot Milk by Deborah Levy (novel, 218 pages, read in 4 days)

- The Incandescent Ones by Fred and Geoffrey Hoyle (SF novel, 156 pages, read in 1 day – I was travelling)