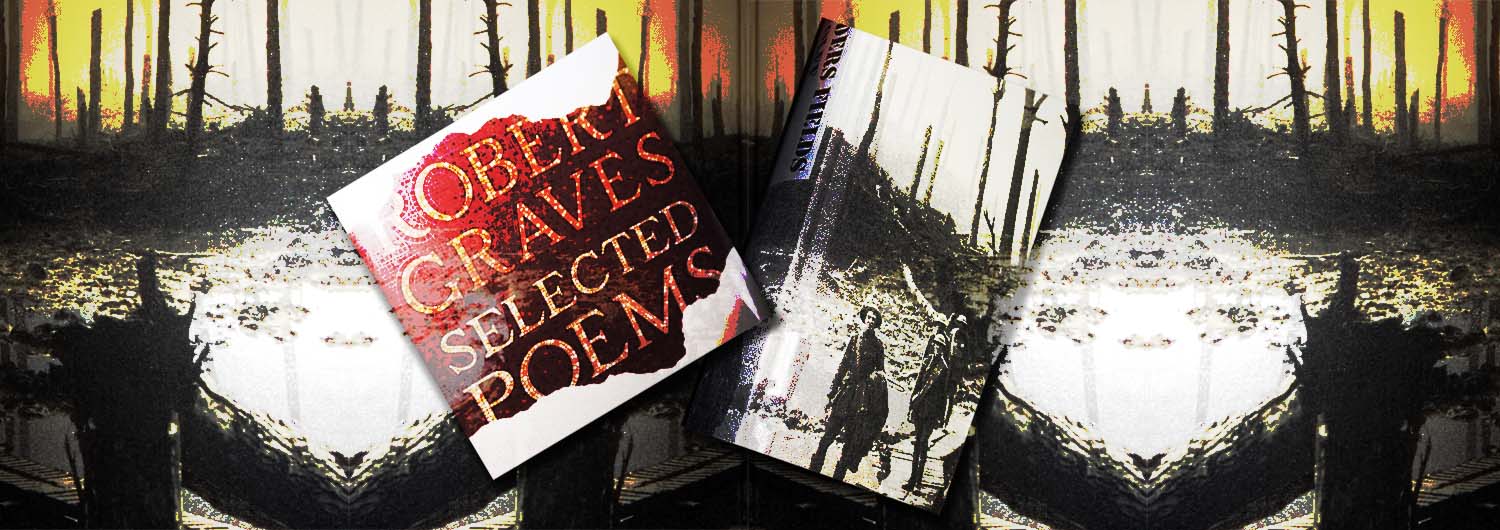

Selected Poems of Robert Graves edited by Michael Longley

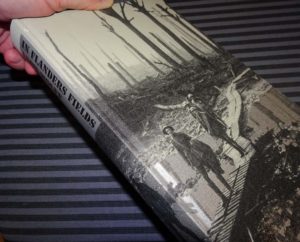

In Flanders Fields by Leon Wolff

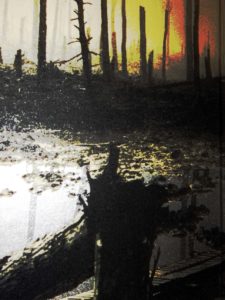

Since the weekend of 11th November I have been reading these two books in tandem. In Flanders Fields is Leon Wolf’s historical account of the 1917 British military disaster known as Passchendaele. Meanwhile, Robert Graves was one of the generation of poets who wrote his earliest successful poetry as a soldier in the trenches of the Western Front. Graves was one of the lucky few who survived more or less intact.

As we sat listening there, and cushioned warm,

War-scarred yet safe, alive beyond all doubt,

The blundering gale outside faltered, stood still…

Poetry his profession

After the war Graves wrote a memoir of his experiences, Goodbye to All That. A classic of angry contempt for the generation of senior officers and politicians who drew Britain into the First World War and then mismanaged the conduct of the war so shockingly. I read it first many years ago as a schoolchild, then again as a teacher of history. I re-read it once more earlier this year and it has lost none of its edge.

Graves went on to write many books, perhaps the most well-known being his fictionalised autobiography of the Roman emperor Claudius, I, Claudius. But he always regarded his fiction as pot-boilers. Poetry was his real love, and his profession. The Complete Poems runs I think to three volumes. This Selected Poems distills them down into a slim collection of 120 pages or so. It includes some of his most well-known pieces as well as a selection of lesser-known but very fine verses. The poems are included in the book in the chronological order in which they were written. It’s possible to see how his style develops while some of his preoccupations remain the same.

When the days of rejoicing are over,

When the flags are stowed safely away,

They will dream of another wild ‘War to End Wars’

And another wild Armistice Day.

Juxtapositions

I’m reading In Flanders Fields a chapter at a time, and interspersing the chapters with two or three pages of Graves’ poetry. It’s interesting to juxtapose the two. By far the majority of the Selected Poems were written during Graves’ long life after the end of the First World War, but his war experiences echo throughout his poetry and, I suppose, throughout his life.

In Flanders Fields, exhausted, terrified soldiers struggle through mud up to their knees at the behest of their commanders. Newspapers report a noble victory. Messages from the Field Marshal’s headquarters to the War Cabinet in London justify the loss of thousands of lives for the conquest of a few yards of Flemish territory. And I open Graves and read one of his children’s poems about ‘The Untidy Man’

Whose fingers could nowhere be found to put in his tomb…

He left his legs and arms lying all over the room.

The Poppy Appeal

In my last Wednesday’s post I mentioned that the Poppy Appeal was instituted in Britain by Field Marshal the Earl Haig. Douglas Haig is one of the main protagonists of In Flanders Fields. He doesn’t come out of it very well. He was 56 years old in 1917. [S]till in perfect health, an imposing figure of a man, gentle in outward manner… [T]otally confident of eventual victory… [C]onvinced the Germans fought for the Devil against him and God…

Haig was a polo player and a cavalry officer. Trained in the 19th century and with experience of Britain’s colonial wars in India and Africa. He was temperamentally and intellectually unfit to fight a war of attrition. Especially one in which the machine-gun and barbed wire featured significantly.

…an old stiff surviving

In a New (bloody) Army he couldn’t understand.

He was, apparently, incapable of learning from experience. He certainly should have done, having had enough opportunity.

The murderous robin

Douglas Haig was a senior officer, present in France with the British Army from 1914. From December 1915 he commanded the British Army on the Western Front until after the end of the war. Yet he was convinced throughout that all he needed to do to win was break through the enemy’s lines and release the cavalry to sweep his opponents away before him. Neither modern technology, not weather conditions, nor the geography of Flanders were relevant to his concept of warfare.

But he knew better, did the Christmas robin –

The murderous robin, with his breast aglow

And legs apart, in a spade-handle perched:

He prophesied more snow, and worse than snow.

Towards the end of In Flanders Fields, the last photograph shows Field Marshal Douglas Haig with his army commanders and staff on Armistice Day 11th November 1918. The caption concludes: [A]fter the war all the famous generals were rewarded with high office except for Hague himself: ‘after stepping ashore at Dover in 1919 he found that his official life was over; he was in effect unemployed’.

Atonement?

Presumably that’s why he had time (as his Wikipedia entry currently puts it) to devote the rest of his life to the welfare of ex-servicemen. He was instrumental in setting up the Earl Haig Fund, now the Poppy Appeal in 1921. It would be nice, but probably overly sentimental to think this was an attempt to atone for the phenomenal loss of life for which he was ultimately responsible.

I’m also publishing this article for the #Blogg52 challenge.