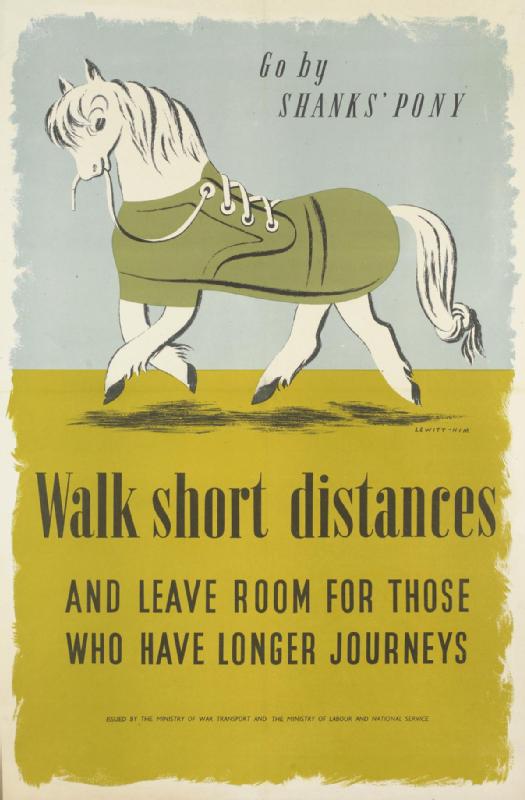

“Shanks’s pony is getting tired, ” I said. Trying for a little humour.

The young man serving me had good English, but not good enough for an obscure idiom from an bygone age. He didn’t look blank so much as a little angry. A little crease between his eyebrows.

“My shanks,” I explained, slapping my legs. “Shanks’s pony,” I said pointing at my feet.

He looked back at the pair of shoes on the counter, soles up.

“Are you sure,” he was speaking careful English, “that you need to have these resoled? They are not worn.”

He was right, and he was wrong. The tread on most of the shoes’ underside was in fine shape despite six or seven months wear. But not on the heels. On the heels the tread was shallow and worn, especially on the outer edges. It’s the way I walk.

The way I walk

I bought these shoes at this shop specifically because it’s possible to send them back to the manufacturer to be resoled. Most modern walking shoes, ones that are cushioned in the right places for my feet, the soles and heels are made in one block. You can’t just take them into a shoe repairer and have a new heel put on. The whole sole has to be replaced. And many manufacturers don’t offer that option. When the soles wear out, they want you to buy a new pair.

Given the price of a new pair, lets say €220/US$260/£190, I really don’t want to be buying new every six months. It took a long search to find a pair of shoes that fit me and that I could send away to be resoled at less than half the price of a new pair. Worth it, I thought.

But now the young man in the shop wonders if I really need them resoled.

I know what he’s thinking. (I think I know.) He’s thinking I’m a rich old man who wants to send these perfectly good shoes away for a piddling little alteration. An alteration that will mean the manufacturers tearing the soles off the shoes and junking them to replace them with something only marginally better. I can almost see him calculating the environmental costs; transport and waste and replacement. (We’re in a shop that sells outdoors gear and markets itself as green.)

But he doesn’t say any of this. He just shakes his head with that little frown between his eyebrows.

“It’s the way I walk,” I say.

“You could walk differently,” he suggests.

Going my own gait

Could I walk differently? Actors sometimes change their gait to convey a different character, I know. But that’s for short periods on stage or on a film set. Could they keep it up, day in and out? I don’t think I could.

My gait is inherited. I tread my shoes down in the exact same way my father trode down his. With my sister, clearing out his home after he died, I remember picking up his shoes and seeing how they were worn. And the first time I saw myself on film, walking away from the camera, how I looked exactly like he did, walking away.

My grandfather, my father’s father, also had problems with his feet. Walking was painful for him some days, as it is sometimes painful for me now.

A great walker

I used to be a great walker.

Let me rephrase that. In my mind, I used to be a great walker. I’ve been trying to remember longer walks that I took as a young man, but I can’t come up with any.

Certainly I walked. I walked the streets of Brighton, my home town, and Leeds when I was a student there for four years. And I’ve walked the streets other cities, of London and York, Bristol, Durham and Birmingham, Sofia and Paris, Vienna and Prague, Brussels and Stockholm. But walking in the countryside? Not so much.

There was a long week on the North York Moors, based at Whitby, when I was a schoolboy. I was 13 or 14 I think, on a geography field trip. One day our teachers took us out and dropped us in small groups in the middle of the moor. Each group had an Ordnance Survey map. (On paper! This was long before mobile phones, apps and GPS tracking.) We knew roughly where we we’d been dropped and we had so many hours to take ourselves to our pickup point. I think my group got lost once, sinking into the mud by a flooded beck, but otherwise we completed our walk and got to our pickup point and felt a great sense of achievement.

Ranging the land

The Ordnance Survey Landranger maps, how I loved them once. I bought them and pored over them for areas around Leeds and Brighton especially. But how much did I ever take them out and walk with them, ranging the land?

I always planned, one day, to walk the South Downs Way, the long-distance track that runs along the ridge of the South Downs from near Eastbourne all the way to Winchester. But I never did, though I walked several parts of it. Day trips over parts nearer to home. But a long walk, from hostel, to pub, to B&B and on, over several days, not so much.

The nearest I ever came to doing something like that was when Mrs SC and I walked most of the length of Hadrian’s Wall from Newcastle to Carlisle. Except we didn’t walk the whole route. There is (or was) an excellent bus service that helped us at least part of the way. We stayed in B&Bs and hostels and walked out from them, but we used the bus to get us and our bags from one to the other.

Round under our feet

And then the last stage of the walk, after I’d been bitten by a dog, was in the back of car as we were ferried down to Carlisle Hospital’s Accident and Emergency. It was my own fault. I thought I’d made friends with the dog the evening before. He was living in one of the places we stayed.

We had been celebrating nearly completing the walk – it was our last evening – and we got back to the B&B a little merry. A little round under our feet, as the Swedish expression is. The dog was alone and on guard duty and I didn’t pay attention to his body language when I tried to pet him. He bit my hand. For years I carried the scars of his teeth around the root of my thumb.

In his footsteps

Living in Sweden as I have done now for very many years, I once had an idea that I could walk from Gothenburg to Uppsala, tracing the route Bulstrode Whitelock took in 1653. Whitelock was the ambassador of the English Republic sent to the court of Queen Christina of Sweden. He arrived in Gothenburg and crossed the country in the middle of winter to negotiate an alliance treaty. At the time Sweden was the most important Protestant state in Europe.

Whitelock kept a diary of his visit. A somewhat unreliable diary. He switched the names of a couple of Sweden’s biggest lakes and he repeated himself. (Either that or he and his companions found themselves surprisingly often dining on “a cow that had died in a ditch”.) I had some idea of following in his footsteps.

Except he didn’t cross the country on Shanks’s pony. He hired horses and rode. I wouldn’t be able to ride because:

a) allergic to horses;

b) scared of horses;

c) couldn’t afford a horse.

But I did think I could walk because, after all, I’m a great walker.

But am I though? These plans rather depend on having feet I can walk on, and that seems to be increasingly uncertain.

Shanks’s pony has heel spurs

My feet are rebelling. Shanks’s pony is getting tired of carrying me around.

I had the first inkling that something wasn’t quite right more than 20 years ago with a tender, inflamed spot on the underside of my foot just in front of the pad of my heel. After I’d been hobbling about for a few days, I took my feet to a doctor who diagnosed heel spurs. I’d never heard of heel spurs before, and rarely heard of them afterwards, until I learned they were what Donald Trump used as his excuse to get out of military service.

Cortisone injections were prescribed and seemed to work, at least I didn’t have any trouble for another 10 years or so, but then. Oh, then.

Bastinado

Here’s what I feel. The whole of the underside of my foot, both feet, from just behind the toes back to the heel, is warm and singing. The soles of my feet feel like they’ve been subjected to a bastinado beating. There are a few pressure points, in particular the pad just to the back of my big toe, where it feels like there’s a blister forming. The blister doesn’t form. There is no blister. It just feels like it’s coming.

And this is just the beginning.

My feet don’t feel like this all the time. With decent shoes and a good pair of specially made insoles I can go for months without major problems. But gradually the heels of my shoes wear down. Or the insoles stop being a flexible, cushioning support as the material compacts into an unresponsive piece of rubber.

My feet don’t react immediately. They carry on feeling okay, compensating I suppose, until suddenly they no longer feel like compensating. Then I have to work out which item of footwear needs to be replaced, shoes or insoles – or both.

My feet, my hobby

The frustrating thing is that once I’ve made the replacement, my feet don’t feel better immediately. It’s like they want to remind me what a bad time I’ve been giving them. Like they are milking my sympathy. So I don’t know immediately that I have chosen right. Was it the shoes after all? Perhaps it was the insoles?

A new pair of shoes costs upward of twice the price of a new pair of insoles. (And a new pair of insoles cost about the same as getting my shoes resoled.) Nowadays it’s a toss up: insoles or resoled shoes. Whichever I go for first, I often I end up paying for both. It’s not a cheap hobby.

And I know, I know there’s an environmental cost as well. It bothers me. I feel bad about sending my shoes off to be resoled when there’s not more than about 15% of them that really needs changing. Some part of approves of the young shop worker. He’s taking the environment seriously. But I still want my shoes resoled, I can’t change my gait and I’m not going to give up walking.

I’ll travel by Shanks’s pony as long as it’ll carry me.