In the first quarter of 2022 I’ve read fourteen titles, from The Wild Girls Plus to The Salt Path. Two books of poetry, one novel in Swedish, six other novels, two collections and three books of non-fiction.

Keeping my reading resolution

Fourteen titles in three months is good. It means I’m on course to keep my reading resolution for the year.

I don’t intend to write about all these now. One title has already feature in its own post: Michael Rosen’s Many Kinds of Love. A couple of the other titles are parts of series. Deborah Levy’s The Cost of Living is one, and I want to hold that over to write about in a dedicated article when I’ve completed the series. (I’ve read Things I Don’t Want to Know. I have Real Estate on order.)

So what follows is a review in brief of a selection of the fourteen.

First up are the two collections, Good Bones by Margaret Atwood and The Wild Girls Plus by Ursula K Le Guin.

Wild Girls +

The Wild Girls Plus (from PM Press in their Outspoken Authors series) includes the titular story, which is one of Le Guin’s anthropological/historical tales. A pre-industrial urban society that exists in a kind of symbiosis with a nomadic hunter-gatherer rural society. The symbiosis involves the kidnapping and enslavement of hunter-gatherer “Dirt” people by the aristocratic “Crown” people in the city. And the slaves’ the co-option into the hierarchy of “Crown” and “Root” (merchant/crafts) people. It’s on the borders of science fiction. (It first appeared in Asimov’s.) Set in some unrecorded past, or a post-apocalyptic future world. Perhaps you could call it a fantasy, although the only fantastical element is the ghost. And even she is more in the mind than in fact. The story does not end well, but it is (of course) well told.

The Plus elements of the book are two essays, a small selection of Le Guin’s poetry and an interview made (I suspect) via e-mail exchange a short while before her death. One of the essays, “Staying Awake”, was originally published in Harper’s (you can see it by following this link).

Modest

The second essay is “The Conversation of the Modest”. Comparing modesty with humility.

Humility is drastic, and often highly visible. Modesty is nothing like so sexy as humility; inherently non-extreme, it consists largely in realistic assessments of one’s gifts and prospects, respectful probability, and distaste for swagger and boasting. You can show off your humility and quite dramatic ways, but modesty, by definition, doesn’t and can’t show off.

The interview includes such exchanges as these.

Q: Perhaps your most famous and influential novel is The Left Hand of Darkness. What’s it about?

A: People tell me what my books are about.

Q: Do you ever get bad reviews? Was one ever helpful?

A: Yes. No.

Q: I’m working on the cover copy for this book right now. Is it okay if I call your piece on modesty “the single greatest thing ever written on the subject”?

A: I think “the single finest, most perceptive, most gut wrenchingly incandescent fucking piece of prose ever not written by somebody called Jonathan something” might be more precise.

(If you didn’t get it, that last reference is to Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal.)

I picked up The Wild Girls Plus by chance, browsing along the shelves of my local Science Fiction bookshop, and bought it because: a) Le Guin(!) and, b) it’s a slim volume. Only a hundred pages. (I’m being tactical. Reading too many fat books has got me in trouble before.)

Good Bones – flash fiction

Another slim volume is Margaret Atwood’s Good Bones. This is not a new title, my paperback copy dates from 1993. As I found it on my bookshelf, I have presumably read it before, but have no recollection of doing so. I find myself bowled over. I ended up reading some of the stories through several time. (Many of them are only a couple of pages long.)

Highlights are Hamlet told from the point of view of Gertrude: By the way, darling, I wish you wouldn’t call your stepdad the bloat king. He does have a slight weight-problem, and it hurts his feelings.

A substitute for war which sounds remarkably like one of those TV reality dancing programmes – Let’s Strictly Dance with the Stars – and which in this day and age seems even more desirable.

The three found texts using Canadian poet John McCrae’s “In Flanders Fields”.

“My Life As a Bat”: In my previous life I was a bat.

This is high quality flash fiction written before the term gained currency. It’s actually described (online, not in the book) as a book of “short fictions and prose poems”. It seems to be a companion piece to Murder in the Dark from 1984. I’m just going to have to track down a copy of that now.

Surreal days in New Paris

So those were my two anthologies. They lead me nicely into talking about one of the novels. The Last Days of New Paris by China Miéville is a surreal science fiction story and alternate history. During the Second World War, a kind of battery is invented by occultists around Alistair Crowley. A courier taking it to Prague in search of the Golem, charges it during an international meeting of surrealists in the south of France. The battery is stolen and taken to Paris where it explodes creating a gate into hell and turning Paris into a city of the living surreal. The Second World War continues long beyond its end in our time-line.

A large part of the story focuses on Thibaut, a young surrealist and resistance fighter. He finds himself teaming up with an American photographer, Sam. She may or may not be on a mission from Alistair Crowley to retrieve the battery, or at least discover what happened to it. Between them they find themselves fighting the Nazis, devils from hell and surreal creatures from the minds and art of many different surrealists.

As so many of China Miéville’s stories, it is an imaginative tour de force.

An offer unrefused

Almost immediately after finishing The Last Days of New Paris, I started reading Mr Rinyo-Clacton’s Offer by Russell Hoban. There are a few points of similarity. Some passages in Offer are almost surreal, and although the story is almost exclusively set in a different capital city – London – at one point three of the characters find themselves in Paris. Where we find: It was raining when we came out into the street, scattered herds of umbrellas moving slowly or swiftly over the glistening pavements.

Jonathan Fitch believes his life is at an end because his girlfriend Serafina has left him. She caught him cheating on her, so it’s entirely his own fault. Miserable and very nearly down-and-out, he lets himself be picked up by a man who calls himself Rinyo-Clacton. Mr Rinyo-Clacton may be the devil; he does devilish things. He seduces Fitch and makes him an offer: a million pounds in return for Fitch’s life after one year. This is the story of what happens to Jonathan Fitch, Serafina, Rinyo-Clacton and an elderly fortune-teller, Katarina.

It’s a very good novel, well told, beautiful in places, frightening in others. I wasn’t so keen on the ending, which does tie up all the knots, but, perhaps, a little bit too neatly.

The plague

The other thing that put me off was that the book felt dated. It was only one thing, but it was quite an important element. Rinyo-Clacton has unprotected sex with both Fitch and Serafina. (Well, he rapes Fitch.) Both of them are concerned that he has HIV and will have infected them with AIDS. The book was written and published towards the end of the 1990s. I lived through that period. I remember it. Still, the widespread fear of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome seems now long ago and somehow unreal.

I wonder if, 20 years on from now, we will look back on the coronavirus pandemic and the hysteria surrounding it with similar puzzlement. As we did with the 1918-1920 influensa pandemic.

Or maybe I’m just a bit insensitive.

I don’t think I am insensitive, but I think I’m more sensitive to things that I feel are directly relevant to me. AIDS and HIV were distant phenomenon even when we were living through the period. I knew people who were likely to be in the firing line, whether gay or haemophiliac, but I didn’t personally know anyone who contracted HIV. Nor did I sleep around or lead a wild, hedonistic life.

As for Covid-19, although I may have contracted and recovered from it early on, the whole period of social distancing, frenetic hand washing and masking up seemed to pass me by. I quite enjoyed being free of obligations to be social or to travel, and living in Sweden we were never subject to the draconian lockdowns of other countries. I was out a lot, I walked, I exercised, I lost weight.

Visceral

Something I find much more visceral is the fear of losing an income, losing one’s home. The news reports out of Ukraine and Poland, the film of devastated cities and streams of war refugees, all feels much more immediate. The final book I want to mention here is one which touched me much more directly.

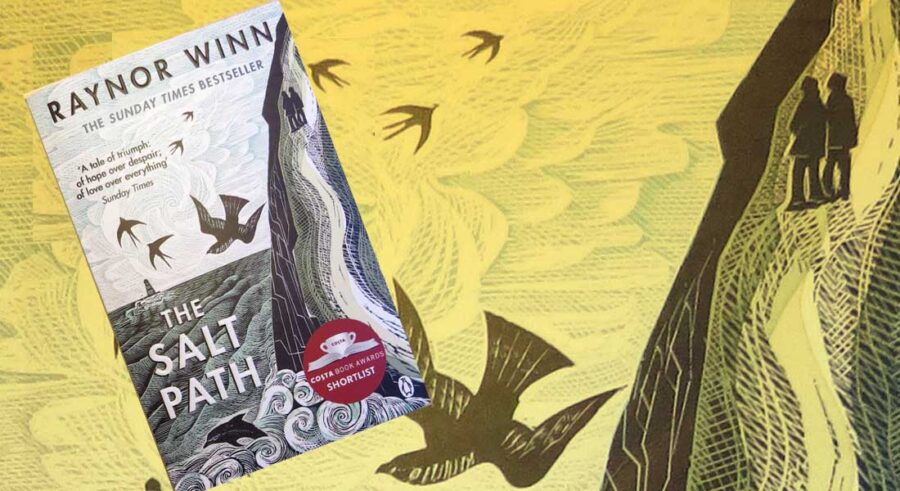

I was recommended to read Raynor Winn’s The Salt Path by friends in my writing group Pens Around the World after I complained about the film Nomadland. I love Frances McDormand as an actor, I think she has an extraordinary face, and the range of emotion she can convey is astounding. But Nomadland as a film was disappointing. It seemed like all these travelling people were voluntarily in pursuit of the American dream. That their life on the road was a bit like being pioneers in the old days of the Wild West. It was adventurous, a lifestyle choice.

The Salt Path

The Salt Path is not like that. It tells the story of Ray (Raynor Winn) and her husband Moth. They were made homeless by a mixture of bad luck, their own trusting natures, the callousness of someone they thought a friend, and the hidebound bureaucracy and cold heart of the British legal system. Moth had also been recently diagnosed with a progressively debilitating, terminal disease. With nothing and nowhere to go, rather than become homeless in the community where they once lived and farmed, they took to the road. It was a way to hold on at least to some dignity.

Ray and Moth decide to walk the 630-odd miles of the South West Coast Path – a bit over a thousand kilometres – from Somerset to Dorset, via Devon and Cornwall. With almost no money and only what they can carry on their backs, these two 50-year-olds find strength, charity, companionship, and ultimately a new home. But it doesn’t come easy and those positive things are not all they find. Although the walking and the fresh air appear to help Moth overcome the worst of his debilitating illness, there is never any real suggestion he will walk himself to health. The disease is terminal.

Having read the last section a couple of times, I find myself anting to revise what I said about Nomadland. There are scenes in the film which imply that the travellers, like Ray and Moth, are putting up a front to save themselves from the social stigma of homlessness. Are reaching for some dignity. But for me, The Salt Path expresses this better.

And on to The Wild Silence

I read my books, often, in the mornings after I wake up, and in the evenings before I go to sleep. One sign that this book affected me more than many others is that, especially when Ray and Moth were facing their biggest crises, I couldn’t sleep after reading it. I had to get up and read more. Now I’ve got the sequel, The Wild Silence, on my to-read list.

So that was my first reading quarter report for 2022. Look for another in about three months!

(Oh, and the illustrations are collages from the covers of my copies of the books. Special mention to Angela Harding who made the cover illustration for The Salt Path, in the background of all my collages here.)

Too Long Didn’t Read

Here are all the books mentioned. As usual the titles link to each the book’s page on Good Reads and the author names to the author’s home page where I’ve been able to find one, otherwise the nearest equivalent or to a Wikipedia article.

- Good Bones by Margaret Atwood

- The Wild Girls Plus by Ursula K Le Guin

- Mr Rinyo-Clacton’s Offer by Russell Hoban

- The Cost of Living (also Things I Don’t Want to Know & Real Estate) by Deborah Levy

- The Last Days of New Paris by China Miéville

- Many Kinds of Love by Michael Rosen

- The Salt Path (and The Wild Silence) by Raynor Winn