So, anyway, John Cleese has written this autobiography and it’s called So, Anyway. With the exception of the final chapter, which is a sort of post-Python Reunion extra track, the story cleverly focuses on Cleese’s childhood and formative years as an author and performer. It finishes during the television recording of the very first episode of Monty Python’s Flying Circus.

As anyone who has read multiple autobiographies will know, the best part is always the author’s description of his or her childhood and growing pains. All the business of public life after the author has achieved success, fame and fortune tends to be largely namedropping and ego boosts. Also, so many of the Monty Python sketches (and the Fawlty Towers episodes – and many of their backgrounds) are well-known. Regurgitating them here, while it would be, I’m sure, lapped up by the fan base (now that’s a disgusting image) would be pretty boring for the rest of us.

So, anyway, it’s clever that the book dispenses with (most of) that. But it’s clever also because of the structure of the story as it is told.

The autobiography follows the conventional chronological route. Childhood, youth, life as a student and the first hesitant years in which our hero discovers his talents, his professional life and the friends who will sustain him. At the same time, Cleese bakes into this mix flash-forward references to his future career with the Pythons and after, and to his philosophical, psychological and sociological interests. This gives a new and different slant on the origins of some of the classic sketches. (Oh, and he’s still in love with Connie Booth – that’s what I see anyway.)

For a wider audience, I guess, Cleese is so identified with the Monty Python gang that many people are under the impression that Monty Python was where his career started. Even if you know something about his history in the Cambridge Footlights – the student revue club at the University of Cambridge – you may not know of his involvement in so many of the stage, television and radio shows that preceded Python. It was good to be reminded of these, and given a more rounded picture of John Cleese before he became a household name.

So, anyway, he comes across in the book as a very intelligent and generally a very kind, rather modest man. A loyal friend and who is always prepared to give credit where it’s due. There are moments though where his sharp intellect and the wicked side of his humour break through. You get the feeling that you would not want to cross swords with him. (He has some cutting things to say about theatre and television critics, for example. You can understand why the Daily Mail is not among his more enthusiastic supporters.)

I want to take a quick look in particular at what Cleese has to say about writing, and of course writing comedy.

I want to take a quick look in particular at what Cleese has to say about writing, and of course writing comedy.

After graduating from university John Cleese was recruited as a writer to the BBC’s Light Entertainment Department. Now, aged about 25, he had a job that involved writing comedy sketches on a regular basis.

I would start the morning with a blank sheet of paper, and I might well finish the day with a blank sheet of paper (and an overflowing waste-paper basket). There are not many jobs where you can produce absolutely nothing in the course of eight hours, and the uncertainty that produces is very scary. You never hear of accountant’s block or bricklayer’s block; but when you try to do something creative there can be no guarantee anything will happen…

But the man who had recruited him, Peter Titheradge, once a writer himself

…was able to calm my incipient panics when fruitless hours were passing. He got me to understand that, if you kept at it, material would always emerge: a bad day would be followed by a decent one, and somehow an acceptable average would be forthcoming. I took a leap of faith and my experience started to confirm this mysterious principle. (p185)

Writers – especially writers who are writing to a deadline – all struggle with the anxiety of wondering whether they will manage. It’s not just getting the words down on paper. It’s also a matter of producing something which is interesting, exciting or in John Cleese’s case funny. Cleese takes up the ambiguous nature of fear. On the one hand how it can block you, on the other hand how it may stimulate you.

Anxiety, he says, is the enemy of creativity.

The more anxious you feel, the less creative you are. Your mind ceases to play and be expansive. Fear causes your thinking to contract, to play safe, and this forces you into stereotypical thinking. And in comedy you must have innovation because an old joke isn’t funny…

Your thoughts follow your mood. Anxiety produces anxious thoughts; sadness begets sad thoughts; anger, angry thoughts; so aim to be in relaxed, playful mood when you try to be funny.

On the other hand you should try to [g]et your panic in early because

Fear gives you energy, so make sure you have plenty of time to use that energy. (p316)

(I think it’s a comfort that, despite this insight, the young John Cleese seems to have had exactly the same problems getting started as me. I’m encouraged to think this is a rather general problem. It was always quite difficult for us [Cleese is writing with Graham Chapman] to get down to work in the morning, and we developed many strategies to postpone doing so… (p368))

Assuming you manage to get going and actually write something, you must be open to the prospect that you will not produce something brilliant every day that you work. Cleese credits Peter Titheradge again with teaching him the importance of finding the thing that is “good enough”. (This is specifically in relation to punchlines, but in my experience it applies generally).

Later in the book, once Cleese and Chapman have established a working rhythm:

Our average rate was about four minutes of screen time a day, which may not sound much, but if sustained would theoretically have given us a movie script every six weeks… (pp368-369)

Theoretically.

John Cleese also has interesting things to say about the differences between writing sketches – even half-hour TV episodes – and whole films.

The need to keep the plot moving all the time is a hugely demanding one – the slightest moment of stagnation and a cinema audience is immediately bored (although a lot of explosions do help to sustain their attention). Add to that the following difficulty in comedy: you cannot make an audience laugh continuously for 100 minutes – human psychology and physiology will not allow it – so you have to plan a sequence of alternating peaks and troughs in the laughter while ensuring that you engage the audience’s attention fully during the passages that are not trying to be funny…

You will now understand why I have managed to write only one really good film script in 50 years (though I contributed to Life of Brian, too). (p382)

The good film script is, of course, A Fish Called Wanda.

So, anyway, I very much enjoyed reading this book, and giggling or even laughing out loud in places. The passages quoted above by no means exhaust what Cleese has to say about writing. And there is a great deal more on many other subjects too. If you know Cleese and his work (and you haven’t yet read the book) you have a treat in store. But even if you know nothing about the man and his career yet still have an interest in the writing process it is well worth a look.

There are also some great tips on keeping control of a primary school class as an untrained young teacher. Take it from me, they also work at secondary school level.

Do also pay a visit to John Cleese’s official website.

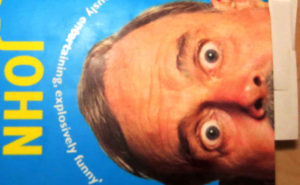

The illustration shows my copy of So, Anyway. There are slips of paper in all the pages where Cleese says something funny or pithy about writing, comedy or teaching. I hate to write in books or stick things in them, but slips of paper are OK. I think it is a bit Pythonesque that they seem to be coming out of his mouth.

This review is also published on Goodreads

I published this originally on the separate At the Quill website. Moved it here 2nd February 2017.

What a wonderful review! I’m definitely curious to read “So Anyway”, even though my knowledge of John Cleese and his work is nowhere near the same as yours John.

Many thanks Aleks. I know more about Cleese now than before I read the book. Perhaps it gave me a little more because I recognise so many of the the people he mentions working with (besides the Pythons). In a way they’re people I grew up with. (I mentioned Jonathan Miller in my previous article here At the Quill.) But even if you don’t know them, there’s always Wikipedia and YouTube if you want to explore further.