When I was in England in February, I managed one day-outing to London. I wanted to visit an art gallery. I wanted to walk along the Thames in the sunlight. And I wanted to drink a cup of coffee at the top of Foyles bookshop after having browsed the shelves and bought some books. I managed all three. (Though I didn’t take any pictures at Foyles – it was a bit too crowded.)

Student days in London’s galleries and museums

Back in the fag end of the 1970s, when I was a university student at Leeds, I used to pass through London regularly. On my way to and from college at the beginning and end of every term. I got into the habit of breaking my journey for an hour or three to visit an art gallery or a museum. A visit to at least one of these remains a must whenever I’m in London.

In later years, the gallery I visit most often is the massive Tate Modern. It’s the one in a converted power station on the south bank of the river, directly opposite St Paul’s Cathedral. It didn’t exist as a separate gallery when I was a student, but has become a magnet since it opened in 2000. On this occasion, however, for reasons of nostalgia, I chose Tate Britain. The original Tate Gallery, on Millbank. The nearest tube station is Pimlico on the Victoria line.

The last time I visited, the Tate was undergoing remodelling and half the rooms were closed. That was some years back and all the disruption is in the past now. The gallery is spacious, calm and fresh again. I wasn’t interested in any special exhibition. (Though one special picture, see below.) Generally, I was out to relive the visits I used to make as a student. Spontaneous exposure to the art of the permanent collection in a few different galleries.

It looks like the permanent collection has been rethought and the pictures shuffled around. Some of the classics have been packed away and some pictures from the archives that didn’t use to be displayed when I was young, are now given place. I think I’d need to visit more than once and spend time in all the different rooms before I felt comfortable with the new display. But that’s good. Art should not be comfortable. Art should challenge and surprise.

Struggle

For me, on this visit, I found my nostalgia struggled a bit with my delight in seeing new things. However, though I looked in some of the rooms of older art, I ended up spending most of my time in the Modern and Contemporary British Art section. Here I was expecting to see new things so I wasn’t over-challenged.

The Tate has a policy letting visitors freely take photos as long as they do so without a flash. The following are some of the images that particularly caught my eye. There’s a theme of destruction and disruption running through them, I think. (Click on any picture to see it full screen.)

Destruction and disruption

The triptych (in my photo) of John Latham’s Belief System is made of damaged and burned books. Apparently the artist used to stage “controversial” book burnings in front of “places with institutional power and knowledge, such as the British Museum.” Books (says Tate’s sign) “represent systems of knowledge that John Latham wanted to undermine.”

There’s something I certainly find very visceral about seeing books destroyed. It doesn’t matter whether they are specifically identified, or anonymous as here. My thoughts go Nazi book burnings and public burnings of the religious texts, to attacks on books and libraries in the USA and elsewhere, and banned books everywhere. I’m not sure my reaction is quite the one the artist aimed for. I don’t think books should be destroyed, not even for art.

Jean Toche’s Typewriter Destruction is another piece from the same era. “It is one of the very few surviving artworks from the 1966 Destruction in Art Symposium.” It “is the remnant of a performance by Jean Toche which took place at Better Books on Charing Cross Road in London.” I’m less disturbed by the destruction of a typewriter.

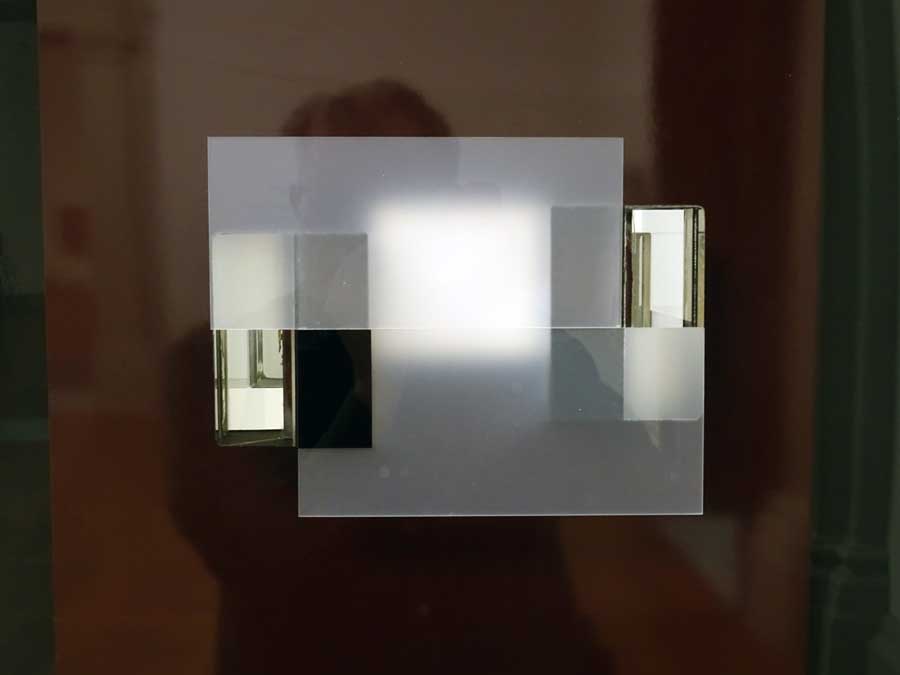

The other two pieces are more disruption than destruction, although Gillian Wise’s Brown, Black and White Relief with Prisms incorporates “prisms … from submarine periscopes”. So there’s a violent connection. Mary Martin’s Spiral (not my idea of a spiral, to be sure) is the furthest from the other three pieces, but the different angles of the chrome cubes reflect different things. Every person’s impression; every person’s photograph of the pieces is going to be unique. It disrupts – shatters – reflections, but in a structured, almost industrial fashion.

Classics

The previous set of images were all new to me. Most of this selection are old friends. The Henry Moor sculpture Three Points was, I see, gifted to the museum in 1978. It might well have have been given pride of place when I was here as a student not long after. It carries the theme of industral precision and threat forward. Those menacing three points coming almost together. Almost grasping. Almost piercing.

Paul Nash painted Totes Meer during or soon after the Battle of Britain (1940-41). “It was inspired by a wrecked Luftwaffe aircraft dump at Cowley in Oxfordshire … ‘The thing looked to me suddenly like a great inundating sea … the breakers rearing up and crashing on the plain … nothing moves, it is not water or even ice, it is something static and dead.'”

“The Second World War meant there was greater industrial output.” Says the Tate’s information sign related to LS Lowry’s Industrial Landscape. “The resulting pollution continued to choke British cities into the 1950s.” I’m not sure if this was the painting I remember from when I used to visit, but Lowry’s cityscapes are certainly a feature of my vision of post-war northern cities. I studied in Leeds at the turn of the decade between the 70s and 80s. Even then I remember thinking they accurately conveyed the feel of the place. (Though Lowry was a Manchester man.)

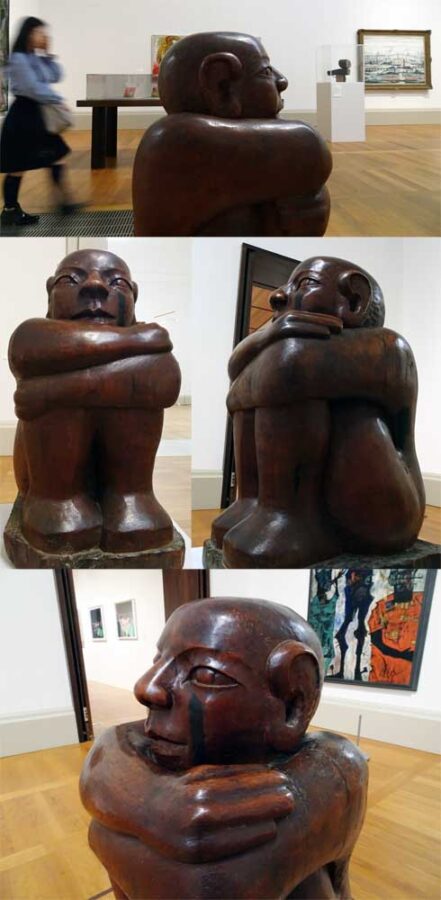

The fourth art work here is the outlier. Not just in that it is related to neither destruction nor industry. Though I think it’s still challenging. Moody was a Jamaican artist who lived and worked in Paris and London. This piece, The Onlooker, is a new acquisition for the Tate. Bought in 2016. This is “Ronald Moody’s image of the artist’s role in society,” says the Tate’s sign.

The Painter and his Pug

Back in the day, when I used to come to the Tate, I would always find time to visit the Hogarth collection. The Tate has a fine set of his paintings and engravings. William Hogarth was a “painter, engraver, pictorial satirist, social critic, editorial cartoonist and occasional writer on art” (Wikipedia). He’s probably most well-known for his story-telling through various series of engravings (The Rake’s Progress, Marriage à la Mode, Gin Street and Beer Lane). Certainly that was how I knew of him when I first came to the Tate.

Finding his self-portrait The Painter with his Pug when I was only familiar with his satirical art made a great impression on me. Ever since, it’s been a fixed point for me in any visit to the Tate Britain. I need to stand in front of it again and relive that first experience.

I couldn’t do it the last time I visited as it was not on display. And I couldn’t do it this time either. When I found where it was supposed to be hanging, it had been replaced by a notice saying Work Temporarily Removed. Why? “Water ingress – 08 Feb 2024”. So the fine, newly renovated Tate has been leaking! I hope the damage is not too great and it’s possible to restore it. In the meantime I have to content myself with the Tate’s on-line version.

Hogarth’s pug’s name was Trump, by the way.

Yes, really!