There’re going to be quite a lot of rails and train-related references in this reading diary entry, bear with me.

On the balcony

It’s been over a month since I sat in The Alchemist to write my last reading diary entry. Now I’m on my balcony at home and set up with a thermos of coffee and my notebook. The same notebook I introduced in my writing diary a couple of weeks back.

In the five weeks since the last entry I have read four novels (Railsea, Giovanni’s Room, Tender is the Night, The Girls of Slender Means), one short book of memoirs (Minnena ser mig), two factual books (Good Sweden Bad Sweden, Factfullness) and one graphic novel (The Arrival). I’ve only got one book on the go at the moment – I’m halfway through Dunstan by Conn Iggulden. But I have Jonas Hassen Khemiri’s Montecore lined up (in the original Swedish). (All the books in this entry are listed separately at the foot.)

I’m no longer worried about strategy and failing to hit my New Year resolution targets. Even if I discount the graphic novel, I’ve read 13 books so far this quarter and I have a week or so in hand.

This entry will spend a little more time on the first three novels mentioned above, and range freely over the rails of my past reading. The other books may not get a look in, but they might turn up in dedicated blog entries later on. They all deserve to.

In the last diary entry the two books I had underway were Railsea and Giovanni’s Room. You’d be hard put to find two more different novels, but they are both well written and I enjoyed reading them.

Railsea

Railsea, by China Miéville, is a fantasy/future world story. Moby Dick meets Thomas the Tank Engine near Treasure Island in a remote post-space travel future world. The world’s oceans are dry plains covered with the tracks of countless pairs of rails. Beneath the surface live voracious, borrowing monsters, the gigantic descendants of our moles and rats. The people of the railsea hunt these creatures from their trains, like whalers of old hunted whales across the water seas.

Railsea, by China Miéville, is a fantasy/future world story. Moby Dick meets Thomas the Tank Engine near Treasure Island in a remote post-space travel future world. The world’s oceans are dry plains covered with the tracks of countless pairs of rails. Beneath the surface live voracious, borrowing monsters, the gigantic descendants of our moles and rats. The people of the railsea hunt these creatures from their trains, like whalers of old hunted whales across the water seas.

But who built the rails of the railsea? And what of the angels that maintain them (as far as they are maintained)? The novel is the story of Sham who learns to be a hunter of the railsea, a scavenger of ancient and off-world artefacts, and an explorer. Sham’s adventures lead him eventually to the end of the line – or to its beginning. The place where all the tears of the world are kept.

I think this is probably intended to be a young adult novel (Sham is in his mid teens), but it amply satisfies even this grizzled old SF lover. It’s easier to get into and read than some of Miéville’s other books. (Though I rate him highly and still think The City and the City is peerless, I wasn’t nearly as wowed by Perdito Street Station or by Embassyville.) Railsea is very inventive and very well told. The characterisation is excellent (and it’s a large cast of characters) and the story hangs together beautifully. Even the axes Miéville chooses to grind in the book are appropriate to the story and satirical rather than intrusive. (He’s China Miéville; he has axes to grind.)

Rail link

One of the interesting things about writing the occasional reading diary is that as I’m writing I find myself seeing links between the books I’ve read. Or links that I have fumbled after come clear. I just noticed a rail link – from Railsea to Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad which I was reading back in February. In Nostromo, too, a railway (from the Port of Saluco to the San Tomé mine) figures as scenery and a plot device.

Further back last September, there was Lenin on the Train by Catherine Merridale. This is an historical account of the long train journey Lenin and some fellow revolutionaries took in 1917. It was mediated by the German government. The “sealed train” brought them on the rails from Switzerland through warring Germany and neutral Sweden to the Russian frontier. To Torneå. The plan was to inject them like a virus into Russia and see what happened. In the short term and from the Germans’ point of view it was a huge success.

And then, at the very beginning of 2017 – in complete contrast again – there was Patti Smith’s brilliant M Train. Eighteen stops on the meditative, melancholy, meandering, musical, mysterious memory train. And masses of mocha. (I mean coffee. I’m just trying to alliterate.)

James Baldwin is not your negro…

There are a few train journeys in James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room too, though I don’t think any of them are significant to the story.

I came to Giovanni’s Room knowing only that it is one of the classics of 20th century LGBTQ+ fiction. I’d not previously read anything by Baldwin, though he’s always been one of those authors in the corner of my mind, lined up to read “one of these days”.

Then early last year I saw Raoul Peck’s documentary film I Am Not Your Negro. This interesting and moving exploration of the USA’s history of racism is based on Baldwin’s unfinished book Remember This House. A kind of memoir of his direct personal contact with three very different American Civil Rights leaders: Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. Most of narrative in the film is by Samuel R Jackson, but there are several clips of Baldwin speaking. I was fascinated to hear his accent – almost British rather than American English.

Then early last year I saw Raoul Peck’s documentary film I Am Not Your Negro. This interesting and moving exploration of the USA’s history of racism is based on Baldwin’s unfinished book Remember This House. A kind of memoir of his direct personal contact with three very different American Civil Rights leaders: Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. Most of narrative in the film is by Samuel R Jackson, but there are several clips of Baldwin speaking. I was fascinated to hear his accent – almost British rather than American English.

So when I saw Giovanni’s Room on the recommended table at Waterstones in Brussels, of course I picked it up.

…and Giovanni’s Room is all white

Knowing next to nothing about the book, the first surprise was to find it doesn’t contain a single black character.

The protagonist of Giovanni’s Room is a young, white, middle-class American. David is living in France, trying to find himself and find his place in the world. He has a lover, Hella, an American woman who is not quite sure she wants to marry him. Hella travels away to Spain to try and figure out how she feels about David. While she is away, David meets and begins a passionate romance with Giovanni, a young Italian waiter and bar keeper.

David and Giovanni’s relationship is doomed. This is in large part because David cannot make up his mind. Can he break with his upbringing and the moral and economic restrictions of home and commit himself to Giovanni? Perhaps even while maintaining a marriage with Hella? Or will he deny his own nature and abandon Giovanni, returning to the States and a “normal” life with his girl?

In the end his indecision causes him to lose both the girl and the boy. Giovanni is tipped by David’s rejection into a downward spiral that leads him to murder and the guillotine.

Speaking of linkage, I expected Giovanni’s Room would link to The Underground Railroad and other expressions of the USA’s awkwardness over race. Instead my mind found links back to a volume of novellas I read in December, The Alphabet of Birds. These stories by the South African Boer author SJ Naudé are set in London and Germany, Venice and South Africa. At first they seem to be about disease and death, but really the common themes are sexuality, love and loss, but above all humanity. These are some of the same things that I take away from Giovanni’s Room.

Barely legal is the night

Barely legal is the night

I also find myself drawing parallels with Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender Is the Night, which I read soon after Giovanni’s Room. Like Baldwin, Fitzgerald is another author I feel I should give more attention. Last year I read The Great Gatsby – I’m trying to decide if it was for the first time or whether I read it before, years ago. Possibly the latter, but if so I remembered almost nothing. I was impressed, reading it, and I’ve been looking out for more. Tender Is the Night caught my eye in a display in my local library.

It turned out to be another story of Americans lost in Europe, though from an earlier period than Giovanni’s Room. While Baldwin’s book grapples with sexuality and double standards, Fitzgerald’s takes on incest and the psychological damage of child abuse and the abuse of the doctor-patient relationship. It also skates pretty close to the edge of paedophilia.

Of the three principal characters, both the women, Rosemary and Nicole, are 16 or 17 when their stories begin. Both are attracted to Dick Diver – the third principal character – though he is significantly older. I don’t want to overplay this. Dick is (I think) about 26 or 27 when he first meets Nicole, about 34 when he first meets Rosemary. The age gap is not huge, but it is significant. Dick does not make a great effort to discourage the girls’ overtures, and he ends up having sex with them both – though pointedly not until each has turned 18.

Don’t misunderstand me, I thought it was a good book with many interesting insights and sidelights. But there were several assumptions and passages I found disturbing. Possibly unfairly, looking back nearly 100 years at what I take to be early 20th century mores.

Arriving at the end of the line

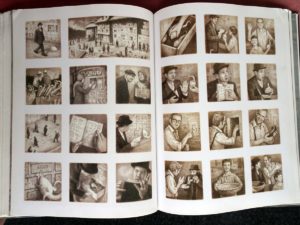

So, those were the novels I wanted to write about. I see I’m now pushing 1600 words, which is a bit over the top for a blog article. Let me just wind up by mentioning The Arrival by Shaun Tan, the graphic novel. This was a recommendation from my Blogg52 buddy Eva Ullerud.

So, those were the novels I wanted to write about. I see I’m now pushing 1600 words, which is a bit over the top for a blog article. Let me just wind up by mentioning The Arrival by Shaun Tan, the graphic novel. This was a recommendation from my Blogg52 buddy Eva Ullerud.

I always associate Shaun Tan with children’s books – mostly because he was awarded the ALMA prize (2011). The Arrival is certainly classified as a children’s picture book in my library. It’s not not for children by any means, but it’s also not not for adults. It’s a beautiful work of visual storytelling, a universal story of the experience of emigration and immigration. And it is done completely without words as the characters try to communicate with gestures and drawings and acts of kindness.

My copy goes back to the library tomorrow, but I am strongly tempted to buy one for my bookshelves. (Except, where would I put it?)

Books reviewed

(Links go to Wikipedia or Good Books unless to author website/webpage.)

- China Miéville, Railsea (plus The City and the City, Perdito Street Station, Embassyville) – author

- James Baldwin, Giovanni’s Room (plus Remember This House and the film based on it I Am Not Your Negro)

- F Scott Fitzgerald, Tender Is the Night (plus The Great Gatsby)

- Shaun Tan, The Arrival – author

- Dunstan by Conn Iggulden

- Factfullness by Hans Rosling et al

- Good Sweden Bad Sweden by Paul Rapacioli

- Lenin on the Train by Catherine Merridale – author

- M Train by Patti Smith

- Minnena ser mig by Tomas Tranströmer

- Moby Dick by Herman Melville

- Montecore by Jonas Hassen Khemiri

- Nostromo by Joseph Conrad

- The Alphabet of Birds by SJ Naudé – author

- The Girls of Slender Means by Muriel Spark

- The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead – author

- Thomas the Tank Engine by Reverend Wilbert Awdry

- Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson

I wrote this article for the #Blogg52 challenge.

Intressant inlägg. Nu blev jag också frestad att läsa Shaun Tans bok 😀

Kram Kim 😀

Det är absolut värt det Kim!

Kram