This is my first reading diary entry for 2021 and, it turns out, my last for 2020. My strategies and tactics for keeping my reading resolution – and four titles I read in the last quarter of 2020.

Strained strategies and dodgy tactics

In 2020, as in the previous couple or three years I set myself the target of completing 50 titles during the year. My strategy, which has worked successfully before, was to read 12 to14 books each quarter. On a granular level (to coin a popular term) about one book a week. These plans went to pot because some of the books I picked up to read were longer than usual. And some of the apparently shorter books turned out more difficult than I anticipated. (See my Fat books post.) In the end, during the last quarter, I was driven to a couple of dodgy tactical manoeuvrers in order to reach my goal.

Example: Towards the end of the year I deliberately picked up Fox 8 by George Saunders. This is a short story bound as a book and took about an hour to read. Cheating? Maybe.

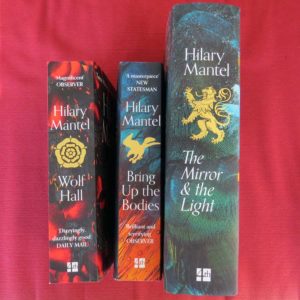

A good number of the books I chose to read in the year found their way onto my shelves by serendipity. I don’t have an over-arching plan for my reading. OK, I do pick out sequences of books sometimes. Last year I read Hilary Mantel’s Thomas Cromwell trilogy in order. (I finished The Mirror and the Light, despite my best efforts, just this side of the New Year.) Nearly 1900 pages for the three books together. Good pages, no question, it’s a great read. But it took time and it contributed to straining the seams of my reading strategies.

Generally speaking, though, I read what looks interesting at the moment. And I rely on recommendations from friends and acquaintances, from the radio and TV book programmes, from magazines. I also like to pick up books that just catch my eye when I’m in a shop or in the library.

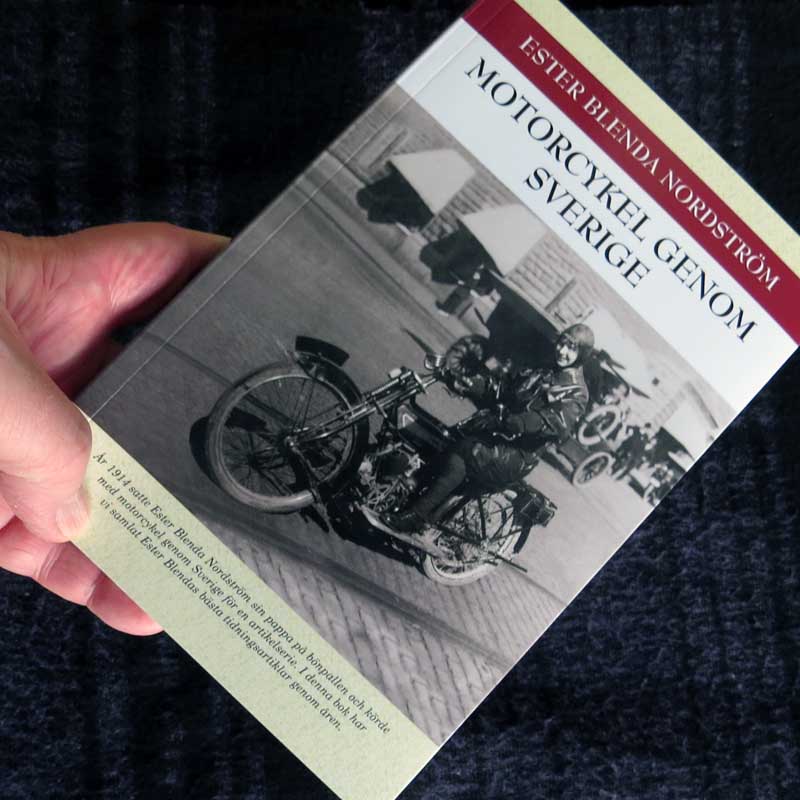

So it was with the first book I want to talk about here: Motorcykel genom Sverige by Ester Blenda Nordström.

Ester’s journey

Ester Blenda Nordström, who wrote her earlier journalism under the name Bansai, was 23 in September 1914. She was already an established journalist at the national Svenska Dagbladet newspaper when she set out on her motorcycle to drive across southern Sweden. This anthology of her writing kicks off with the seven articles she wrote documenting her journey. While the great powers of Europe were falling into war, Ester, with her father on the pillion, was discovering among other things how the main road across southern Sweden was blocked at frequent intervals by farmers’ gates.

Ester Blenda is remembered in Sweden principally for being an early investigative journalist. At the time there was consternation in middle-class Sweden at the numbers of young women from the countryside who were emigrating to America. Why was this happening? Ester Blenda took service as a maidservant (piga) in a large farmhouse in Södermanland. Her series of reports about the conditions that maids had to endure were published in the spring of 1914. Popular and, by some accounts, provocative, the articles were collected in a book (En piga bland pigor) published later the same year.

Ester’s Reportage

This book is not that book (which I will track down and read in 2021). Instead it’s an anthology of Ester Blenda’s other reportage. Ranging from public scandal over the length of women’s hat pins in public transport (1913), to a description of the country house she came to own (1936). In between is a selection of articles, some very good.

In northern Finland in 1918 civil war, bad weather and disease had left whole villages starving. Judging by these articles, Ester seems to have been instrumental in organising and bringing in famine relief from Sweden.

From 1920 there are pieces she wrote while sailing to South America and crossing the Andes by mule from Argentina to Chile. Then, from 1924 and 1925, more reports from a car journey through France and Spain. In June of 1925 she was in Kyoto in Japan reporting on the aftermath of a major earthquake. (Perhaps the Kita Tajima earthquake which took place in May that year.) And in 1926 or 1927 she was in Beijing celebrating Christmas.

The book ends with a few pieces published in the mid-30s and a memoir of her journalist friend and mentor Elin Wägner.

Motorcykel genom Sverige is published by Swedish publishers Bakhåll, who also appear to have republished several of Ester Blenda’s books including that first investigative effort, so I plan to get hold of a copy later in the year. I’ll read it in Swedish. It seems that En piga bland pigor was translated and published in English, but Internet searches on the translated title, A Maid among Maids, plunge me down rabbit holes of fetish wear and BDSM. Fascinating, but not really what I’m looking for!

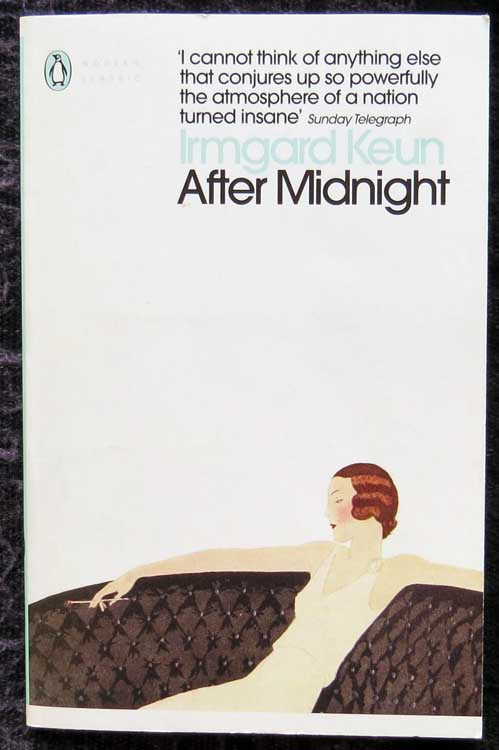

After Midnight

I picked up Ester Blenda’s book in the same shop as After Midnight by Irmgard Keun (translated by Anthea Bell). Another young woman, 19 year old Sanna, but this one is fictional. I knew nothing of this book or its author before coming across it in the shop, but the blurb and the cover caught my interest. (Though to be entirely honest I was also attracted by the book’s relative thinness. Only 138 pages. I could already see my my strategies weren’t working, so choosing it may have had a tactical element. But set that aside.)

This is the story of Sanna, who just wants to live her life in peace, enjoy herself, fall in and out of love, and have a night out with some friends. Unfortunately she’s in Frankfurt in the early 1930s. Hitler is in power and is visiting the city on this very night. The local Nazis and their supporters are all around and already making life more complicated, even for Aryan teenagers like Sanna.

The banality of evil

Hannah Arendt wrote about the banality of evil and After Midnight does a good job of illustrating it. The Nazis and their supporters are banal, petty, self-satisfied, lazy, obtuse, greedy. Keen to settle old scores and not particularly ideological or very violent, except now and again, when it suits. Reading the book I hear so clearly how the world Irmgard describes is echoed today.

Irmgard Keun published successfully in Germany, but saw her books banned when the Nazis came to power. In 1936 she left Germany for the Netherlands, where she wrote After Midnight. The copyright page of my Penguin Modern Classics edition claims the book was originally published in Germany in 1937. I’ve been unable to find out much about the history, but that seems unlikely. I suppose it might have been published clandestinely. But more likely (surely) it was published in German in the Netherlands. As far as I can discover Anthea Bell’s is the first translation and only came out in 1985.

According to her Wikipedia page, Irmgard Keun had a curious war. Trapped in the Netherlands following the German invasion, she was believed to have killed herself. There were notices to that effect in several European papers. She returned to Germany and lived out the war under an alias in Cologne. Wíkipedia quotes her daughter: “she always said that the Nazis took her best years”.

After the war she was for a time a homeless alcoholic and spent several years in a hospital psychiatric ward. Towards the end of her life, thank goodness, she was rediscovered. From 1977 till her death in 1982, her last few years saw her regain some financial stability and a degree of independence.

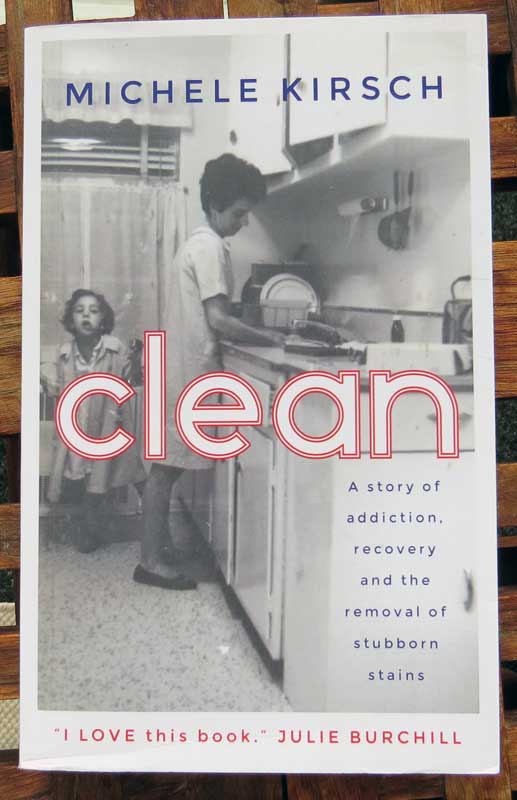

Clean

I’m a little torn about this next book, Clean by Michele Kirsch. Torn in several ways. In terms of my reading strategies, I’ve chosen to count this twice. I mean, I read it through cover to cover twice during the year, so I think I’m justified. It’s just that, doing so, feels a bit like I’m cheating.

Another reason I’m torn has to do with why I read the book twice.

Disclosure. I met Michele Kirsch on the novel writing course I took last May and June. (I met her virtually I mean, this was 2020 and the course was online.) Michel was a fellow participant. She was following the course because although she had then written and published this book, it’s an autobiography and she wants to write a novel.

I’m sure she’ll write her novel and it’ll be a good novel. She is a good writer, and Clean is a well written book. I could see that the first time I read it through and I didn’t change my mind on the second reading. Nor did I feel the urge to skip through the book the second time. My problem, which remains, is down to me rather than to Michel’s book. You see, I can see how funny the book is. Intellectually. It just didn’t make me laugh. Not once. (Michele, I’m sorry!)

Addiction, recovery and the removal of stubborn stains

In July Clean won the Royal Society of Literature Christopher Bland Prize. It’s a prize awarded to debut authors over the age of 50. Clean deserves the win. It’s a well written account of Michele’s cross-Atlantic life, harrowing in places and very sad, but with a vein of gallows humour running through it. But for me the sad part, the harrowing part, outweighed the humour.

In the 1970s, in New York, Michele is a child when her father dies in a freak train accident. Prescribed Valium to overcome her anxiety, she grows up with the drugs, supplementing them with alcohol. Unable to complete her education or hold on to work, Michele tries her hand at a variety of different jobs. The one job she is able to do without qualifications, both as a teenager and an adult, is cleaning, so it’s something she comes back to repeatedly. The title of the book plays on that work as well as holding out the promise of her eventually becoming clean from her addictions.

It’s a great relief to realise that she does get clean. That there is a happy ending. A happy ending of sorts. Michele writes that addiction is relapsing and remitting by nature. You can be clean for ages and then one year, two years, 10 or 20 years down the line, a little “why not, just the one” goes off in your head and before you know it you’re back in the madness.

Hopefully the success of Clean and the coming success of her first novel – and of her subsequent novels – will keep the madness permanently at bay.

The most important story

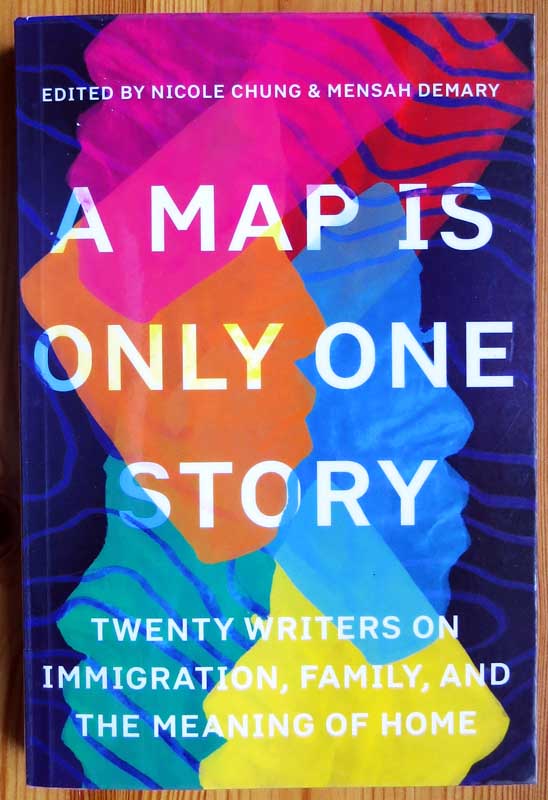

The last book I want to write about in this my last/first reading diary entry of the year is A Map Is Only One Story.

My local library had this on display in the English language short stories section. To be fair, the English language short stories section is very small, and novels and books of poetry often crop up there. Essays about “immigration, family and the meaning of home” are more unusual. However, though I picked it up thinking it was a book of short stories, I read it as a book of essays with great enjoyment.

Twenty different authors, all of them in some degree immigrants, ponder aspects of identity. There is a kaleidoscope of styles here, from straightforward reportage to what seems to be fictionalised storytelling, to memoir. There is even a graphic story about food and cooking and the importance of being able to feed one’s family: I have forgotten how to speak two languages. But, I have learned this one. Against a picture of a plate of food. (The author of that is Shing Yin Khor.)

How to get back home

The second essay in the book, “A Map of Lost Things” by Jamila Osman, provides the title for the collection. A country is impossible to contain, she writes. A people are impossible to boil to the silt of parchment. A map is only one story. It is not the most important story. The most important story is the one people tell about themselves. She writes about her father, a Somali refugee and immigrant who provides for his family by driving a cab. My father knew how to get everywhere; it was what we admired most about him. … But even he… could never figure out how to get back home.

The cover announces A Map Is Only One Story as the “first published anthology of writing from Catapult magazine“. Catapult has what looks like a very interesting website. I think I might be spending some time there in 2021.

So that’s it!

Another year another shelf of books. Next week or the week after I’ll publish the complete list for anyone who’s interested. In the meantime, if you want to read some more of my reading diary entries for 2020, look below.

Too Long Didn’t Read – all the URLs

Author links go to the author’s home page or nearest equivalent where I can find one, books link to their entry on Wikipedia or GoodReads.

- A Map Is Only One Story eds Nicole Chung & Mensah Demary (Catapult)

- After Midnight by Irmgard Keun

- Clean by Michele Kirsch

- Motorcykel genom Sverige by Ester Blenda Nordström

- Wolf Hall, Bring Up the Bodies, The Mirror and the Light by Hilary Mantel

- Fox 8 by George Saunders