Jana Kippo is the protagonist of a recent successful trilogy of novels in Swedish by Karin Smirnoff. (The first is now available in English, though I didn’t know that till just now.) For this week’s blog post I thought I’d have a shot at translating a little section from the third book. I think it neatly encapsulates the whole of the trilogy. See what you think.

The photograph

There was a picture. When we were little it stood on the chiffonier in the front room.

Every birthday mothern had a new picture taken of us.

When we were twelve fathern wanted to start a new tradition. The whole kippo family would be in the picture.

We looked like a normal family.

When we were thirteen bror killed fathern with an axe. We d just had our birthday. The photographer d been booked. Only we hadn t had time to go there yet.

Getting the photo took was something we looked forward to. We shared a hope. As if we could become like the people in the picture. A family. A clan. Growing children. Proud parents.

Tha couldn t hold on t kill im till after they took picture i asked bror.

Det fanns ett kort. När vi var små stod det på chifonnején I salen.

Sen for jag hem, Karin Smirnoff

För varje årsdag lät modren ta ett nytt kort på oss.

När vi var tolv ville fadren inför en ny tradition.Hela familjen kippo skulle vara med på bilden.

Vi såg ut som vilken familje som helst.

När vi var tretton slog bror ihjäl fadren. Vi hade just fyllt år. Fotografen var bokad. Vi hade bara inte hunnit dit.

Att ta det här kortet var något vi såg fram emot. Vi delad ett hopp. Som om vi skulle kunnat vara som personer på kortet. En familje. En sammanhållning. Barn som växte. Stolta föräldrar.

Kunde du inte väntat med att slå ihjäl fadren tills efter fotograferingen frågade jag bror.

Norrland and Yorkshire

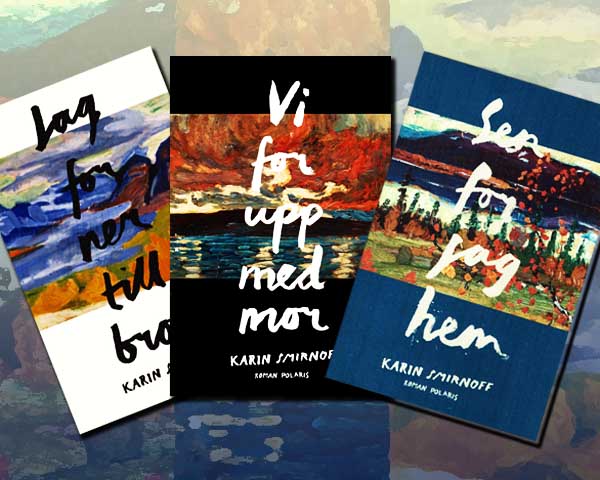

Karin Smirnoff’s first published novel, Jag for ner till bror was nominated for the Swedish Publishers’ Association August Prize in 2018. She followed the first title with two more following the story of the same protagonist, Jana Kippo. The novels are set (mostly) in the Swedish far north, in the forests and mountains, and along the Baltic coast of Norrland.

The landscape and the villages of Norrland are poor, hard and cold, and in these books the people who live there are likewise. Mired in rural poverty, many of them aging, tenacious, hardbitten, short-spoken. There’s truth in the characters, but there’s also a degree of cliché. Reading the books, I couldn’t help but mentally remove some of the people and some of the situations to rural Yorkshire.

The clichés are similar. Yorkshire people pride themselves on being straight-talking, down-to-earth, rough-hewn, not fancy, not la-di-dah. That’s why, when I made my translation, I gave Jana a Yorkshire dialect.

Spare, yet rich

In Smirnoff’s books, the landscape, the incidents and the personalities are reflected in the language she uses. Short sentences with little punctuation. Each sentence has an initial capital letter and ends in a full stop, and that’s about it. Names are uncapitalised and usually run together, so first and family names become single agglutinated units. The protagonist is not Jana Kippo but janakippo, her twin brother is not Bror but bror. The language is spare, but larded with dialect words and grammatical structures. Just as the story, superficially simple, is filled with depth and complexity. (It’s funny too, in places, in a very understated way.)

And yet it is not that difficult to read, even for a non-Swede. True, it took me time to get into the first book, but about 50 pages in, I found I was reading quite easily. I read the second volume last August. Now I’ve just finished the final book.

Jana Kippo, her story

The trilogy begins with Jag for ner till bror (literally “I travel down to Bror”), continues in Vi for upp med mor (“We travel up with mother”) and concludes with Sen for jag hem (“Then I travel home”). So the three titles in themselves, in short, undecorated sentences, sum up Jana’s journey. First down (from Stockholm) to her brother, an alcoholic who lives alone on the family’s smallholding in the village of Smalånger. (The name of the village literally translates as “narrow remorse”.) Then she and Bror travel up (with their mother’s coffin) further north to bury her in the village she came from. Finally, after Bror’s death, Jana travels home.

Fathern, mothern

Jana and Bror call their mother and father modern and fadern. These aren’t dialect words, though they could be. In Jag for ner till bror, Jana says she can’t remember why they started to use the terms, but perhaps it was after something heard in a Norwegian children’s TV show. They sound like they mean “the mother”, “the father”. This is appropriate as both parents have behaved abominably to Jana and Bror. Depersonalising them with these terms is a way for the children to retaliate. No ma, mum or mom, no pa or dad. I chose to use mothern and fathern.

As I wrote at the beginning, Jana Kippo’s story, or at least the first book, is out in English (as My Brother) this year from Pushkin Press. Judging by the extract provided on the publisher’s website, the translator has gone for a conventional translation into standard English. I think it’s a pity, but also understandable. I’m not sure I could keep up the dialect for a whole book. Still, I find myself a little challenged to make a translation of the same section of Jag for ner till bror, and do it my way. Just to see if I can.

Watch this space!

I think your first attempt at translating janakippo was brilliant!

I sometimes ponder what a translation of novels with a lot of Swedish dialect would be like. It’s a pity if the translator doesn’t even try to put some “markers” in the text.

Did you read any of Kerstin Ekman’s Jämtland novels in translation? I think that would be very interesting, her language is not as provincial as Smirnoff’s, but beautifully poetic.

Thank you Lena. It was a little bit of fun. As I wrote, I doubt I could keep it up for long. That said, I’m about half way through the chapter extract from Jag for ner till bror that Pushkin is using on their site to promo Anna Paterson’s translation, My Brother. If I complete it, I’ll post it at TheSupercargo later.

It’s getting on for forty years since I heard people use Yorkshire dialect in real life, so I’m not going to make any claims for the accuracy of my usage now. Time flows on – I wrote “thirty years” in the previous sentence, and then counted and had to go back and change it.

I’ve only read Kerstin Ekman’s Händelser vid vatten, and only in Swedish. Maybe I should look out for the English translation and make a comparison.

Very interesting. I stumbled on your post when I was describing to my brother something I worked on a few years ago.

I had the exact same thought as you when I first read the Jana Kippo trilogy. I read it shortly after having read Paul Kingsnorth’s brilliant novel The Wake. Kingsnorth uses an invented language to set the mood of medieval England. The language borrows from modern English, Old English, and some other Germanic languages. Kingsnorth felt that it just isn’t right to have the narrator, a medieval Englishman, speak modern English. At first it is hard to read, but after a few pages you don’t even notice.

So I set out to translate the Jana Kippo Swedish into an artificial language. Then, I – like you – discovered that the books had been translated. Any way, here are my first few pages. Unfortunately the foot notes don’t paste well (I pasted them in below the text).

Here are my notes on the idea:

yanakippo swinglish

Karin Smirnoff refers to the language that jana kippo speaks as kippospråket, the kippo language. https://spraktidningen.se/artiklar/2020/06/jag-anvander-dialekt-som-krydda. Most pronounced is the lack of punctuations, capitalization, and that first and last names are run together, janakippo eskilbrännströms and ingelahansson for example.

Karin Smirnoff uses the words and phrases of north sweden dialects to give spice to the prose.

That’s all that is necessary to give a sense of a different swedish being used. However, I wonder what a kipposwinglish would be like. So, in this translation I do follow all the conventions of the original: no punctuation save for period, no capitals, and run-together names.

Further, I use deliberate spelling errors to conjure up how swedes tend to mispronounce English. W becomes v, j becomes y, etc.

One of the dialect features in Jag for ner till bror is suffixes that are slightly different from in standard Swedish, most notably on havan. The sea. I build on that. In Swedish, definite articles are suffixes. There are several, -en, -et, -an. For example, house is hus; the house, huset; bus is buss; the bus, bussen; old lady is gumma, the old lady, gumman. As a tool for getting a bit of different language for jana kippo when she speaks english, I add definite articles to the end of words. So, for example, the house in janakipposwinghlish is houset. I am confident that after a chapter or two, the reader will not even reflect on the weird words.

I am also going to use a few Swedish words; especially, when the word used in the dialect of the original differs markedly from “standard” swedish.

I rode down to bror

a novel by

Karin Smirnoff

translation: Pehr Jansson

ey trevyld down to bror /1. ey tuk thebus /2 along coasten and hupped ov att efyran /3. Thyn ey valked /4 towards townen.

Thesnow fell hyrd and thevind blew theroad shut. Flakesen wrestled thyir vay into me low boots and anklesena froz as in childhood.

Bilar could of stupped for my thymb but no bil cume. It was a payr of kilometers to my brors house and roaen was upwyrds.

Our parents lved everttAube and thyn they deyd.

Vinden cut through coaten. A button was lacking on top and snowen melted agaynst throaten. ey should have been there now. Snowen made landscapet anonymous. Had ey even passed eskilbrännströms. ey hurried on. As long as schoonern can go and who has said that just you came into vorlden.

A bundle pressed out from snowfoggen. A hunkering männischa in head-wind. At first iey couldnt see if it vas man or voman. Vinden turned. Snowmittens fell. For a few seconds creaturen disappeared but then vinden decided to give its most and in eyet of stormen i suddenly saw who it was.

It wasnt anyone i knew.

What a weather he said when he came close and ey nodded in reply. He vondered whereabouts ey was going and ey said to kippofarmen.

Thu måst of took a vrång tyne at fyrken he said behind e scarf. Thu should ov taken a right. Ey can show thu he said in a friendly way. Between scarfen and cappen ey gleaned nose and eyes. ey tried to catch his eyes but he only looked forward.

We turned but stomachcAmpassen said the opposite. He offered me his mittens.

It has been a long time since anyone shared mittens with me. I didnt get how i could have gone wrong.

We turned and vent back. Leaning against vinden like a child on a frostmo fell /5.

He lived near and his name was yon.

My name is yana /6 i said and i am going to visit my bror.

And your bror is named bror he said. I know who you are.

Where are you yourself going i screamed to overpower vinden which had newfound power.

Nowheres he shouted back. I just like bad weather.

He pointed at a lesser road where faint tracks could still be seen in snowen. I live a bit yonder. Come along to my hus and warm yourself a while then you can continue when snowen has petered out.

I hesitated because i didnt recognize him and i should have. Further i knew that the road led to eskilbrÄnnströms house.

Do you live in ghosthouset i asked and he nodded.

I didnt know it was liveable. Do you have a family or do you live alone.

There you can only live alone he answered.

Vinden continued to whip snow against necken. Facet had grown numb long ago. I followed him in.

He built a fresh fire in stoven and pulled out a pink wool blanket that he draped over me as i sat there in my longyohns and camisole on kitchen couchen while clothesen dried on a chair.

It is from umEdalen he said. When crazysEna moved out they had an auction.

There was something familiar about roomet and i thought i must have been there before. Kitchenet was rundown in a soft and calm way. Besides couchen there was a gateleg table and some homemade västerbottenchairs a tall cabinet and a clock that ticked but didnt show correct time.

It seemed he lived here. Probably slept in gustavianen where i now sat and hung my legs because feetsen didnt reach flooret.

Do you live in kitchenet i asked and cupped my hands around the hot cuppen he handed to me.

Yes usually he answered. At least in winter. In summeren i sleep in atticken or in parloren.

That parlor i asked and held onto a vague memory of a ceiling painting. He nodded and slurped like olefolk from a coffeesaucer with a sugarlump between teethen.

I saw parloren in my minds eye. A pair of yellov rubberboots on a black chest and that chesten couldnt be opened. How I finally used a flat ironbar that i had found stuck in the ground like a rusty surveyors mark. I had worked it in between liddet and chesten and pried until locket gave with a snap.

Twentyfive years later i cant remember what was in chesten. Maybe it was nothing but entrapped air.

Do you know who my brother adam is he asked.

I didnt know.

We played on the hayloft he said. We made flips from a roof beam and landed in the hay.

Adam was a few years older and always dared more than i no matter how i bent fearet. That day he had stolen cigarettes and wondered if i wanted to try. Since i didnt want to seem childish i took a glennwihoutfilter in the hay and put it in corneret of mouthen while my brother struck fire on a match. It was not meant that smoken should get stuck in throaten and produce a caughattack which made it so i dropped my glennwithoutfilter in the hay. To find a glowing cigarette in a hayloft is in principle as hard as to find a needle.

The freshly cut hay might have extinguished cigarreten on its own but the more we poked around the more oxygen we stirred up and suddenly fires flashed up all around.

I lowered myself down to byre flooret.

1/ “bror” means brother in Swedish. However, it is also a first name. It seems everyone refers to Jana’s brother as “bror”. Since, the jannakippo language is devoid of capitalization, even for names, it is ambiguous as to whether “bror” is “brother” or the brother’s name. I have opted to always use “bror” except when unambiguously brother. While on that, she refers to her mother as “modren”. “The mother” in Swedish would be “modern.” One might hypothesize the “modren” was simply the kind of mispronunciation that a child makes and that it just stuck. A similar transposition is used for Jana’s father, fadren. In both instances, I use modren and fadren.

2/ Karin Smirnoff talks about the jannakippo language. It is pretty straightforward. However, there is a certain dialect involved. You see it in words like “havan” – the sea. That is not standard Swedish – the sea would be havet. In Paul Kingsnorth’s brilliant novel The Wake, the author uses an invented language to set the mood of medieval England. The language borrows from modern English, Old English, and some other Germanic languages. Kingsnorth felt that it just isn’t right to have the narrator, a medieval Englishman, speak modern English. At first it is hard to read, but after a few pages you don’t even notice.

I feel the same way about Karin Smirnoff’s novel. Modern English isn’t what jannakippo would narrate her story in. So, I try something similar to Kingsnorth here. I may use some Swedish words, especially when the north swedish word differs from “standard” Swedish. Also, I move articles and plural forms to become suffixes. In Swedish, articles are suffixes. -en, -et, -an means the, e.g., huset is the house. Sometimes, it is plural. Husen, houses, husena, the houses. I am adding Swedish suffixes for articles – it is something swedes do when using English words while speaking Swedish – with confidence that the reader will soon figure out what it means and read it fluently, like in The Wake.

3/ The E4. Europa Way four. The main north-south highway along easter sweden.

4/ I also use some common mispronunciations. V for w, y for j.

5/ A cultural reference to a Swedish children’s film from the 1940s – Barnen på Frostmofjället, Children from Frostmo Fell. Fjäll means mountain or alp. Archaic English fell is a cognate.

6/ Again phonetics. J is pronounced soft in swedish. jana and john would be pronounced yana and yon, respectively.

yanakippo swinglish

Karin Smirnoff refers to the language that jana kippo speaks as kippospråket, the kippo language. https://spraktidningen.se/artiklar/2020/06/jag-anvander-dialekt-som-krydda. Most pronounced is the lack of punctuations, capitalization, and that first and last names are run together, janakippo eskilbrännströms and ingelahansson for example.

Karin Smirnoff uses the words and phrases of north sweden dialects to give spice to the prose.

That’s all that is necessary to give a sense of a different swedish being used. However, I wonder what a kipposwinglish would be like. So, in this translation I do follow all the conventions of the original: no punctuation save for period, no capitals, and run-together names.

Further, I use deliberate spelling errors to conjure up how swedes tend to mispronounce English. W becomes v, j becomes y, etc.

One of the dialect features in Jag for ner till bror is suffixes that are slightly different from in standard Swedish, most notably on havan. The sea. I build on that. In Swedish, definite articles are suffixes. There are several, -en, -et, -an. For example, house is hus; the house, huset; bus is buss; the bus, bussen; old lady is gumma, the old lady, gumman. As a tool for getting a bit of different language for jana kippo when she speaks english, I add definite articles to the end of words. So, for example, the house in janakipposwinghlish is houset. I am confident that after a chapter or two, the reader will not even reflect on the weird words.

I am also going to use a few Swedish words; especially, when the word used in the dialect of the original differs markedly from “standard” swedish.