The beginning of October seems like a good time to publish a reading diary entry. I’ve just completed the ninth reading month of the year and I’m on target to keeping my New Year resolution of 50 books read. My running total is 42 books read so far. (Plus one longish short story published as a novel – Zadie Smith’s The Cambodian Embassy – and Shaun Tan’s graphic novel, The Arrival, which I can’t count as it contains no words.) I feel quite sure I’ll easily read another eight books before the end of the year. Even ten more, which will take my average up to one book a week.

This diary entry covers the eight books I’ve read since my last reading diary entry here on 15th August (Dunstan to Apex). I’m pleased to say they are an eclectic mixture: three literary novels (including one I think might nowadays be classified as YA), two biographies, a literary memoir, a diary, a work of fantasy and a science fiction/adventure yarn. Two of them were re-reads, possibly three.

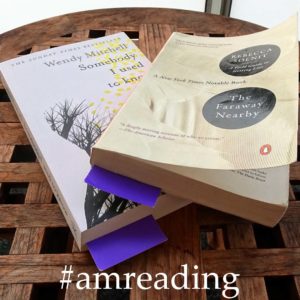

I’ve already written a review of Wendy Mitchell’s moving account of dementia from the inside, Somebody I Used to Know. I combined it with a review of Rebecca Solnit’s literary memoir The Faraway Nearby, also a book well-worth reading. You can follow this link if you want to see the review.

Guest of Reality

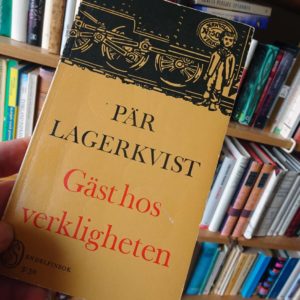

The one Swedish novel I read this time was Gäst hos verkligheten by Pär Lagerkvist. Lagerkvist (1891-1974) was a poet and novelist who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1951. I’m told he’s a better poet than he is novelist. Perhaps that’s true. Gäst hos verkligheten (Guest of Reality in the English translation) didn’t impress me much. It’s the story of Anders, a member of large tribe of brothers and sisters who are the children of a railway worker and his wife in a small town somewhere in Sweden.

The story starts when Anders is about five or six years old and follows him till he is – I guess – in his later teens. Throughout this period he has a morbid fear of death. There doesn’t seem any good reason for this, but it colours the way he behaves towards his family and imbues his observations of the world with a sense of dread. Quite early on he finds his way into the icehouse that serves the rail station’s restaurant and bar. The clammy darkness, the exhalation of winter from the pile of blocks of ice preserved in insulating sawdust, all carries a sense of foreboding. A foreboding that hangs over the novel and over Anders’ youth.

Inevitably someone he knows dies – his grandmother – and her death, funeral and wake are described realistically and in detail. But she was an old woman and worn out by her life as a peasant farmer. Her death was hardly unforeseeable or shocking. Quite early on I expected Anders’ father to be killed in a railway accident – he seemed to live dangerously. That would perhaps have given substance to the boy’s dread. But no. Father lives, as does Mother. All the brothers and sisters too and even the grandfather and more distant relatives.

Teenager before the concept

The book falls into about four sections of differing length, and the third was, I thought, the most interesting. In this section Anders is a teenager before the concept of teenage became current. (The book was originally published in 1925 and seems to describe a period of time before the First World War. The concept of teenage/teenager wasn’t current before the 1940s at the earliest.) Pär Lagerkvist’s description of Anders’ teenage angst rings true. It shows that many of the attitudes we associate with teenage behaviour today – the narcissism, the self-doubt, the desire to be included and the desire to be left alone, the yearning for love and the rejection of love – these things have been associated with teenagers for over a hundred years.

A bit of research shows Gäst hos verkligheten to be autobiographical. Some of the things in the novel, including Anders’ fear of death, Per Lagerkvist shared. Someone more into Lagerkvist as a literary figure would surely have a better appreciation of this book than me, but overall I found it disappointing.

Jean Brodie

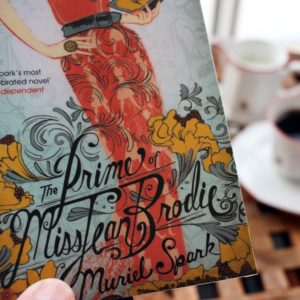

Quite different is The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie by Muriel Spark. After Gäst hos verkligheten I feel I ought to have read Spark’s earlier novel Memento Mori, but, no. Earlier in the year I read The Girls of Slender Means and then discovered that 2018 is the hundred-year-anniversary of Muriel Spark’s birth. As I enjoyed The Girls, I decided to look out some more of her writing and that was what took me to Miss Jean Brodie. It’s another very good book although, I think, not quite as inventive technically.

Starting the book (as I wrote earlier) I was under the impression I’d read it before, long ago. But reading it now I realised that everything I thought I remembered of the book comes from the film. The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, the film, was released in 1969 – eight years after the book – with the the 35 year old Maggie Smith as the eponymous Miss Brodie. I suppose I saw it on television sometime in the 1970s.

It didn’t matter. The only slight dissonance is that I hadn’t realised “the Brodie set” – the girls Jean Brodie makes into her groupies – were all so young at the beginning. In the film I think they were all portrayed in their teens. In the book they are primary school age when Jean Brodie teaches them.

The leader of the gang

As a one time teacher, I recognise Jean Brodie’s behaviour. I’ve seen it, perhaps not often and certainly not as fully developed, in former colleagues in several different work situations. Certain teachers in certain situations can definitely face the temptation to cultivate a “set” of pupils. A gang, a group of supporters, fans. Establishing control in a class can involve identifying group leaders – the pupils the other kids look up to and from whom they take their cues – and then winning them over. But what happens if you replace these natural leaders with yourself?

This is what Jean Brodie does. But the authority she achieves is shallow. By succumbing to the temptation to make herself the leader of the gang, she exposes a deeply immature and flawed personality. The story of the novel is how she loses her authority without understanding why, and how she is betrayed.

Rats and Gargoyles

If I was unsure whether or not I’d read Jean Brodie, I’m absolutely certain I’d read two other titles. Rats and Gargoyles by Mary Gentle and Espedair Street by Iain Banks. Espedair Street is the Young Adult novel, Rats and Gargoyles the fantasy novel.

Rats and Gargoyles is set in a world inhabited by humans and intelligent, man-sized rats who live together in a huge city. Both human and rat society are hierarchically structured, but the rats are clearly in the ascendant. The social structure of the rat-human society has a strong feel of 17th century France. The rats are prancing, preening, sword wielding, theological aristocrats; the humans are downtrodden labourers, rude mechanicals, engineers and magicians. Theology and magic are relevant because of the other great power in the world. The Decans – 36 immortal demi-gods who rule the 360 degrees of the world’s circle – and their supernatural gargoyle attendants. The Decans are the true powers who keep both rats and men in check. But great changes are threatening and one Decan in particular has plans to bring about his own death and so create something new.

Both possible and impossible things

As an exercise in literary creation I think Rats and Gargoyles is exemplary. It creates a world inspired by the fantasies of 16th and 17th century alchemists, Rosicrucians, followers of the Kabbalah, Freemasons, Hermeticism. (Illustrations from several books associated with these groups are repurposed in Rats and Gargoyles.) At the same time it presents several interwoven plot-lines with lots of action, some wonderful characters and detailed descriptions of both possible and impossible things. There is pathos and emotion and genuine humanity and a satisfying conclusion (if you have the stamina to read the book to the end). It’s not for everyone, that’s for sure, but it’s a step and a half up from your run-of-the-mill fantasy novel. And Mary Gentle as an author is well worth exploring for all her other work.

Just as I love Mary Gentle, I love Iain Banks, though for very different qualities. Banks (who sadly died all too young) was also a story teller and a science fiction author of standing. But he wrote regular “literary” fiction too – or maybe fiction that isn’t so easily pigeon-holed.

Espedair Street

It was only now, reading Espedair Street for the umpteenth time, that it occurred to me it would probably be classed as a YA novel today. Though maybe not. The descriptions of drunkenness, sex, drug-taking and (some) violence might be too much for the genre. But much of the novel is an adolescent fantasy about the rise to success of a rock band at the tail end of the 1970s. Of course it then goes on to detail the band’s implosion, so less of an adolescent fantasy there perhaps.

It’s told in flashbacks by the protagonist, Daniel Weir, aka Weird. He describes himself as tall and clumsy with an ugly face. Weird was the bass player and songwriter for Frozen Gold. Banks invents a band on the level of Queen, Black Sabbath, The Who or Fleetwood Mac. Immensely successful from the very beginning, with increasingly outrageous and elaborate stadium concerts, all the money and fame undermine the band. Then a couple of dramatic on-stage failures result in death and a guilt trip for Weird.

(I should add the book is also very funny in places, often at Weird’s expense.)

Remaking himself

Weird lives in a Victorian folly in a Glasgow that is remaking itself as a post industrial city. He tries to conceal his real identity from new friends and strangers alike as he struggles with his guilt. The flashbacks aside, Espedair Street takes Weird from the brink of suicide to the possibility of redemption. Like Glasgow, he may be able to remake himself

Some years ago I tried to get a copy of Espedair Street as an audiobook. I thought it would particularly appeal to one of my nieces. It seemed then this was the only book of Iain Banks that hadn’t been recorded. I wasn’t sure why, but I guessed the music would make it difficult. I see there’s an audiobook available now, but it looks like the publishers chickened out over the music. Pity.

Well, that was six of the eight books. The word count is telling me I ought to stop now. The two I’ve not written about are The Diary of a Bookseller by Shaun Bythell and To Your Scattered Bodies Go by Philip José Farmer. I’ll have to hold them over for separate reviews later – or include them in the next reading diary entry.

For now though, that’s what I’ve been reading.

From Reality to Espedair Street

Here’s a list of the books I’ve read since Apex Hides the Hurt. As before I’ve added in some of the other books mentioned in the entry. Links on the books are to the relevant pages on Good Reads. The author links are to the authors’ English professional homepages where I’ve been able to find them. Otherwise the author links go to their English Wikipedia entry. (Wendy Mitchell’s link goes to her Twitter profile.)

- Espedair Street by Iain Banks

- The Diary of a Bookseller by Shaun Bythell

- To Your Scattered Bodies Go by Phillip José Farmer

- Rats and Gargoyles by Mary Gentle

- Gäst hos verkligheten by Pär Lagerkvist

- Somebody I Used to Know by Wendy Mitchell

- The Cambodian Embassy by Zadie Smith

- The Faraway Nearby by Rebecca Solnit

- The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie by Muriel Spark

- Memento Mori by Muriel Spark

- Arrival by Shaun Tan

I’m also publishing this article for the #Blogg52 challenge.

I read The prime of miss Jean Brodie in school, in English so I guess it must have been for the language studies. I only remember it made an impression, not why, and that it made me think of a teacher in fourth grade. The thought I got was: she must be feeling young! The teacher in question was, I guess, around 35 but in my view she was ancient: 70 or older. It was quite an astonishing discovery.

Kram

Eva

It’s always interesting when perspective shifts and you see something from another angle. I will always remember a very concrete example. I was teaching a class of 12-year-olds in Sundsvall my third or fourth year in Sweden, standing-in for the class’ regular teacher. They had an art class. It was “free subject” so there were a lot of cats and cars and cartoon superheroes. But one of the little boys decided to draw a portrait of me. The result was impressive. I mean much better than I would have expected and certainly better that I could have made at his age. But it was also a bit horrifying. He hadn’t quite got the idea of perspective, but he was reaching for it – except he drew me with small legs, larger torso and huge head. There was something else odd about it too, but I couldn’t quite put my finger on what it was. He gave me the picture and I took it home and showed it to my wife. She pointed out he was drawing my face from below looking up. And that was the first time I realised I had hair growing from my nostrils that people could see!